As a new retrospective at London’s Whitechapel Gallery evidences, Rodney was an expert of fragmentation, distortion and the obfuscation of a unified self-image

‘To whom does the black body belong?’ is a question as pertinent to sport and entertainment as it is to western science. ‘Industrialised medicine, as a product of racial capitalism, reinscribes basic tenets of property rights onto the body,’ the scholar Zoé Samudzi writes in a 2022 essay for the Architectural Review. The history of Black bodies as the testing ground for modern medicine has been well documented, from slave owners loaning and selling the enslaved to physicians for experiments, to the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study; from Eugen Fischer’s sterilisation experiments on Herero women in German South West Africa (now Namibia), to the case of Henrietta Lacks, an unwitting and unremunerated source of cells – the famous HeLa cell line – which continue to provide invaluable medical data. But, to paraphrase a question the artist Carolyn Lazard asks in a conversation on the artist Donald Rodney: ‘can the medicalised Black subject speak back?’ Rodney’s practice offers a rejoinder by hijacking the visual codes of carceral and medical discourses (the two often overlapping), and their proprietary claims to controlling and surveilling the Black body.

Taut and diligently executed, Visceral Canker, a retrospective of Rodney’s work currently at the Whitechapel Gallery, contends (like all surveys of its kind) with comprehensiveness. Its Spike Island debut in 2024 claimed to feature ‘all of Donald Rodney’s surviving work’ – a minor but telling mistruth in the absence of Camouflage (1997), shown exclusively at Whitechapel Gallery, which speaks to surveys’ fetishism of completeness. While the exhibition’s near-exhaustiveness is a boon for those who’ve seen few of his works beyond reproductions, its import lies equally in its archival materials, revealing the workings of a brilliantly restless and idiosyncratic mind, through a selection of the artist’s prized notebooks and other ephemera. For Rodney, who lived with sickle cell anaemia and endured frequent hospitalizations, pain and immobility, his notebooks were like a studio in miniature. In Visceral Canker, they reveal his catholic tastes in source material including Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities (1859), the Brooks slave ship diagram, and David Wojnarowicz’s image of a burning house, to name a few.

Born in West Bromwich in the early 1960s to Jamaican parents of the Windrush Generation, Rodney attended Trent Polytechnic (now Nottingham Trent University) where, under the influence of artists Keith Piper and Eddie Chambers – and as a part of the BLK Art Group – he embraced an overtly politicised artistic mission. How the West Was Won (1982) is an early expression of this commitment. The painting is a childlike rendering of the cowboy and Indian archetype, which it approaches with dark humour, while a toy pistol once affixed to the work, now lost, heightened the uneasy proximity between play and violence.

Visceral Canker’s Whitechapel iteration, however, opens not with this work – the earliest in the show – but with Self-Portrait: Black Man Public Enemy (1990), which contrary to the title’s suggestion does not include an image of the artist. Instead it presents four found images of Black men from newspapers, their eyes obscured by black bars, alongside a generic identikit sketch that is almost comical in its vagueness if it were not for the carceral violence it emblematises. Across multiple works, Rodney ingeniously appropriates X-rays, reclaiming control from an illness and a medical establishment that defined much of his life. As Lazard notes, the artist ‘couldn’t not think about the fact that his body was constantly being imaged’. So where does a body under such scrutiny seek refuge? For Rodney this is found in fragmentation, distortion and the obfuscation of a unified self-image.

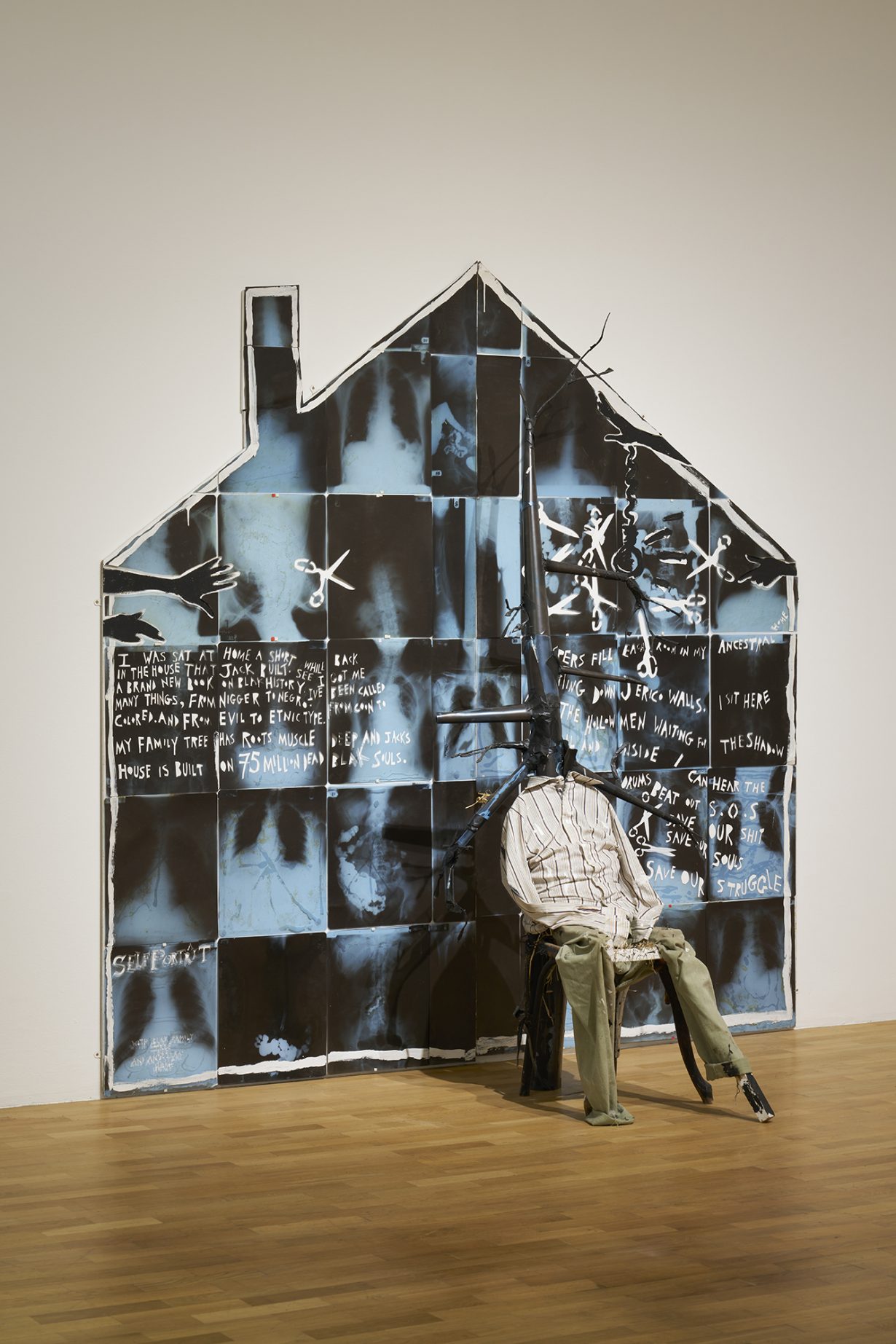

The House That Jack Built (1987) is a grid of Rodney’s chest X-rays in the shape of a house – a recurring motif – before which sits a scarecrow-like effigy impaled by a burnt-out tree to evoke lynching. Another tableau, comprising grids of used X-ray film as a support for Rodney’s oil pastel figures, Britannia Hospital 3 (1988) (of the series of three, only two survive), is populated by a Special Patrol Group officer (part of a London police unit renowned for their violent tactics), a patient likely representing Rodney, a migrant nurse, and an echo of Frida Kahlo’s The Broken Column (1944) bearing the face of Cherry Groce, who was paralysed by a Metropolitan Police bullet in 1985. Like its counterparts in the series, the piece functions as a contemporary history painting, rich in allegory, political urgency and compositional drama.

Rodney’s use of medical material continues in Visceral Canker (1990), the work that lends the exhibition its title. Composed of plastic tubes, intravenous drip bags, wires and electric pumps circulating imitation blood, the piece includes the coats of arms of slave trader Sir John Hawkins and Queen Elizabeth I, who funded Hawkins’s expeditions, painted on wooden panels. Here, the notion of Black bodies as the lifeblood of Empire is made literal. (Unfortunately, when making the original piece, Rodney was prohibited by Plymouth city council from using his own blood.)

Among the most captivating works in the exhibition’s Spike Island iteration, My Mother, My Father, My Sister, My Brother (1996-7), is notably absent from the Whitechapel show due to its fragility. The tiny roughly hewn house constructed from a fragment of Rodney’s own skin, taken from an abscess he developed following a hip operation, and held together by dressmakers’ pins, stands as a shrine to mortality. Its counterpart, In the House of My Father (1997), is a large photograph of Rodney holding the sculpture in his palm. The artist had intended to create a second image with the sculpture placed on his tongue, like a communion wafer, but this never materialised. What Rodney did manage to create, with both sculpture and image, are emblems of the family home as protective yet vulnerable, as a repository of histories at once personal and intimate as well as collective and public.

Psalms, an automated wheelchair created with art and technology researcher Mike Phillips (who Rodney met at the Slade School of Art in the 1980s), moves through the gallery space. The piece debuted in 1997 at South London Gallery, where it stood in for the ailing artist in absentia at the opening of the exhibition. Even today, Psalms still manages to exude pathos, perhaps shot through with less comedy than at its original showing, where it navigated the crowd more awkwardly than it does the open space at Whitechapel.

The animatronic sculpture Pygmalion (1997), a mechanised effigy of Michael Jackson in blackface – dressed in his iconic military jacket, Jheri curl and rhinestone glove – convulses inside a glass case. Rodney was fascinated by Jackson’s media portrayal, likening it to a Victorian sideshow. And so with this play on Jackson’s racial metamorphosis we encounter a nod to the exhibitionary complex of funhouses, freak shows and the minstrel performances they birthed. At Whitechapel Gallery, the excesses of Pygmalion‘s grotesque are amplified by Camouflage (1997), a large-scale patterned work onto which a racist slur is writ large but remains imperceptible except on very close inspection, its violence hidden in plain sight.

This is the dark, twisted comedy that pervades several of Rodney’s works and notebooks, both of which brim with wordplay and a keen sense of Black history’s cruel ironies once referred to by the artist as a ‘vicious cabaret’. It’s a formulation that hints at his interest in the intersections of race, entertainment and their attendant pageantries, an element materialised in the installation Doublethink’s (1992) rows of cheap sporting trophies, each one engraved with racial stereotypes: ‘Black life is encircled by melancholy’, one reads; ‘Black people are inadequate and bitter’, goes another. Alongside racism’s deleterious effects there lies its absurdity, a dizzying combination made evident by Doublethink’s ironic merging of monuments to achievement with the language of debasement.

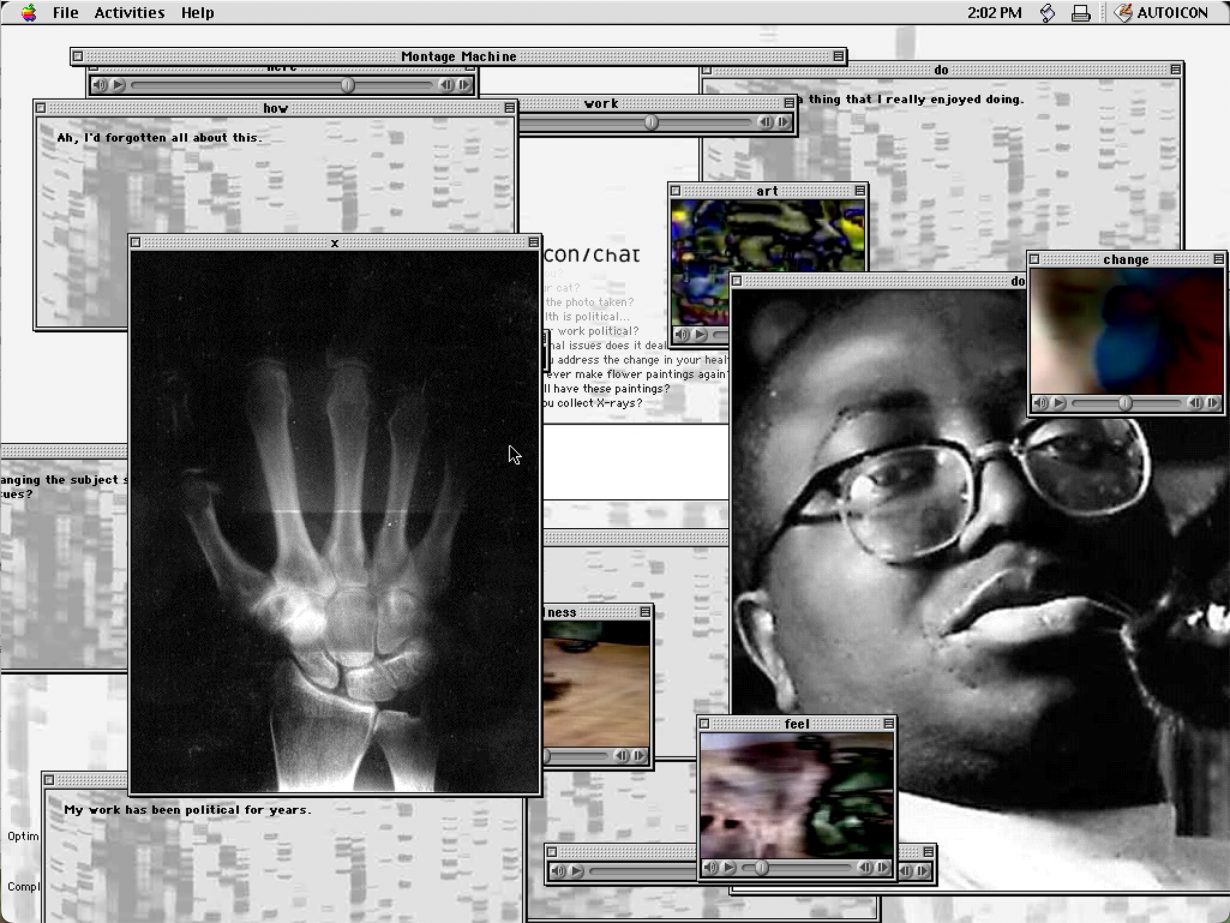

With the posthumous Autoicon (2000), also developed with Phillips, the many facets of Rodney’s impossible-to-unify character are brought to bear. Originally a web- and CD-ROM-based interactive work that drew from the artist’s writings, interviews and voice recordings, it allowed users to converse with a simulated Rodney, via a clunky interface, by typing questions into a chat box. In its original networked version, Autoicon was affected not only by its users but by the entire evolving ecosystem of the internet. In this sense, Rodney’s body was distributed across various locations, echoing then-current developments in avatars and locating bodies in cyberspace. The experience of interacting with the work today is awkward and uncanny; for all its claims to longevity, it’s an artefact of its time, both functionally and aesthetically.

Beyond foreshadowing contemporary debates around digital afterlives and machine learning, Autoicon anticipates computer desktop performances and documentaries like Martine Syms’s Misdirected Kiss (2018), Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013) and Zia Anger’s My First Film (2018), where overlaid windows are montaged together. It also prefigures how the internet and other technologies have made art more accessible to those living with illness, debility and disability not simply as users but as creators. To return, then, once more to how the medicalised Black body speaks, the narrator remains obscure in Autoicon and we are left wondering ‘who or what is speaking’, as writer and curator Richard Birkett writes in his 2023 book on the work. Is it the artist, the computer, or his friends and carers who helped realise his work for years (playfully referred to as ‘Donald Rodney plc’)? In his ambition to create a legacy beyond his lifetime (Rodney lived to just thirty-six), there exists a refusal to be remembered through official medical records alone. Instead, the artist troubled the idea of singular authorship, objective documentation, and the ailing body as separate from its environment.

Tendai Mutambu is a writer and curator based between London and Barcelona