50 years on: assessing the legacy and limits of the feminist art-historian’s pioneering essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’

Three weeks after The New York Times published an investigation into sexual harassment allegations against Harvey Weinstein, the American art historian and pioneering feminist Linda Nochlin died. Author of the essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ (ArtNews, 1971), in which her dissection of the notion of ‘great men’, the ‘male genius’ and the systemic privileging of white men launched a new era of feminist art history, Nochlin witnessed the trailer to the detonation of Weinstein’s career. But she didn’t get to see the avalanche of artistes of all kinds – film and theatre directors, actors, photographers, musicians, comedians, artists, chefs and more – mainly men, that landed in a heap at the foot of the #MeToo movement.

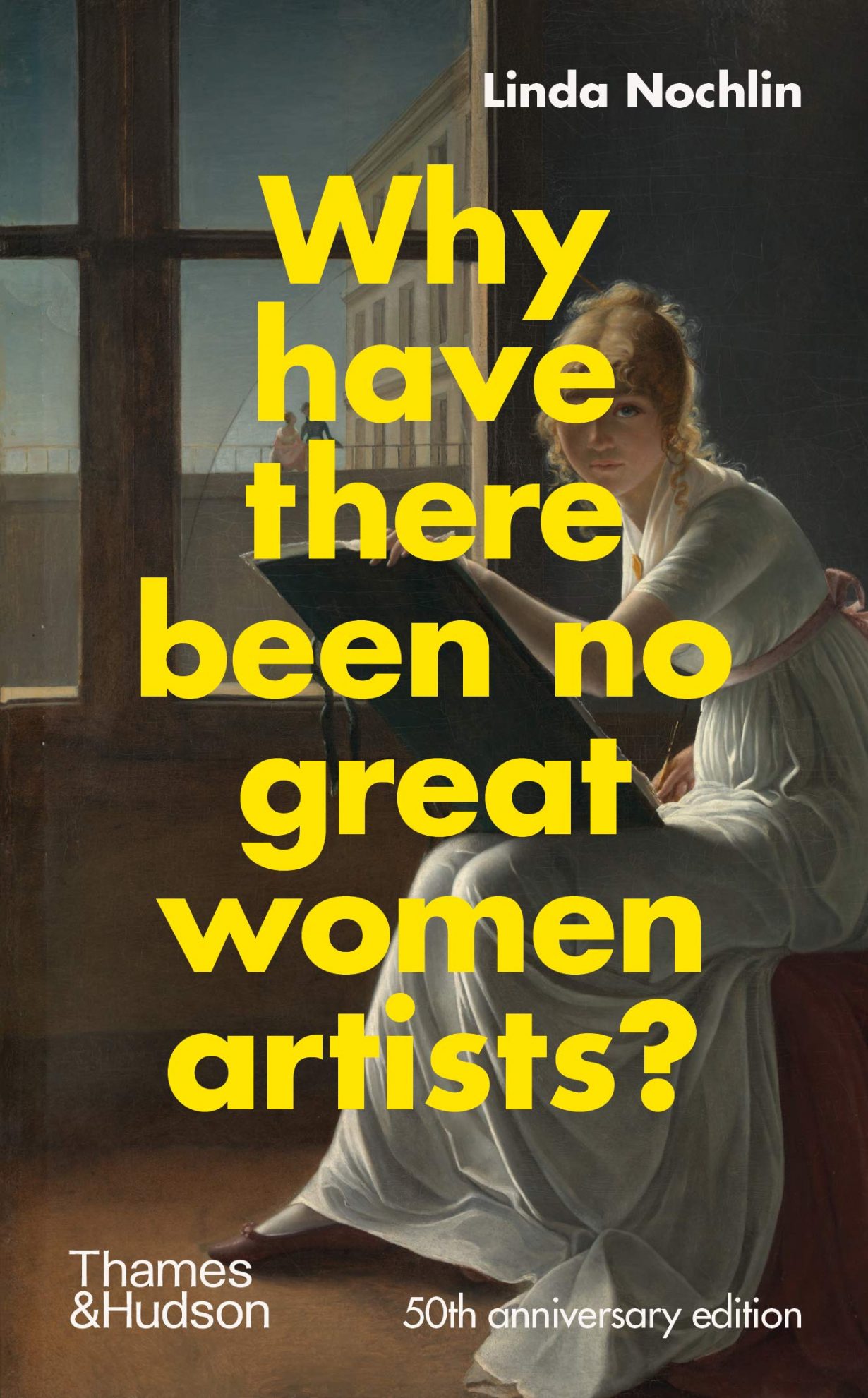

‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ and its 2001 sequel, subtitled ‘Thirty Years After’, are now republished in a fiftieth-anniversary edition, accompanied by a foreword by academic Catherine Grant. That first essay was sparked by a question put to Nochlin in 1970 by New York gallerist and dealer of Old Masters Richard Feigen (who died this week) when he sought her advice on collecting paintings by women artists. Nochlin’s 4,000-word response carried the (now rarely reproduced) subtitle: ‘Silly questions deserve long answers.’

Nochlin swiftly dismantled ‘the myth of the Great Artist – subject of a hundred monographs, unique, godlike – bearing within his person since birth a mysterious essence, rather like the golden nugget in Mrs. Grass’s chicken soup, called Genius or Talent’: a fairytale perpetuated by the ‘romantic, elitist, self-individualising substructure on which the profession of art history is based’. She shone a light on the institutional and structural barriers to women and minority groups. ‘If women have in fact achieved the same status as men in the arts, then the status quo is fine as it is,’ Nochlin wrote. ‘But in actuality, as we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class and, above all, male.’

To offer a bit of context, at the point of publishing ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) had just resurfaced after it was first proposed nearly five decades earlier. It passed Congress and the Senate in 1971, but fell short at 30 of 38 State ratifications needed to enter the US Constitution by a deadline of 1979. And despite numerous attempts since then, almost one hundred years since it was first proposed, the ERA – ‘Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex’ – still has not been written into an institution that is supposed to uphold the basic tenets of US society.

Nochlin’s follow-up essay might not have the same punchy impact as the original, the reason being that after ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ was published in 1971, women in the arts started to gain greater visibility: feminist art was documented contemporaneously, and art historians began conducting an archaeology of women artists throughout history. But it does offer a valuable appraisal of the first essay, highlighting the development of intersectional feminism during the 1990s that takes into account the way in which different and overlapping lived experiences (including race, sexuality, class, disability, religion) combine to create different modes of discrimination. White women largely benefitted from second-wave feminism, but it would take a couple of decades for queer, trans and women of colour to be included in these conversations. This remains an important axis from which to consider Nochlin’s 1971 essay today.

‘Those who have privileges invariably hold on to them, and hold tight’, she wrote. ‘Thus the question of women’s equality – in art as in any other realm – devolves not upon the relative benevolence or ill-will of individual men… but rather on the very nature of our institutional structures themselves and the view of reality which they impose on the human beings that are part of them.’ While Nochlin takes as points of reference European and American artists from the Italian Renaissance to the realists of the nineteenth century (her area of study), and on towards the mid-twentieth century, mentioning along the way the likes of Artemisia Gentileschi and Lavinia Fontana, Rosa Bonheur, Käthe Kollwitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, it is this crucial argument that continues to make Nochlin’s essay a relevant and formative text for students of art history – it’s where this writer first learned about how historic systemic inequality and exclusion (in the context of Europe and North America) has had a lasting impact on the lack of advancement of anyone who isn’t a white man. Nochlin continues: ‘Most men, despite lip-service to equality, are reluctant to give up this ‘natural’ order of things in which their advantages are so great.’

The text was ground-breaking, written with wit and in a conversational style rarely seen in academic studies, but its confinement to the worlds of academia and art also reveal its limitations, both in terms of accessibility (knowing where to find it) and the fact that it doesn’t directly reach ‘any other realm’. These days, it would be difficult to find a museum curator who had not read Nochlin’s text. And yet it was only after the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements entered popular consciousness that gallery programmes offered any significant shift to reflect these social issues. Even after its explosiveness in the academy, and its position as a keystone text for feminism in the artworld, it has taken nearly half a century, the fall of a ‘great’ man, and then many men, as well as multiple police killings of people of colour, to reach a mainstream awareness that no longer accepts ‘greatness’ (or success, or seniority) as an excuse for abuse of power.

Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, 50th anniversary edition, published by Thames & Hudson