The late artist evoked both freedom and confinement in her surreal prostheses and bodily machines

Sometime during the late 1960s or early 1970s, the German artist Rebecca Horn received a bag of white feathers from a friend. ‘It took me a year to pluck up the courage to put my hand inside and touch them, owing to a bad childhood experience with a headless chicken,’ she recalled in a 1993 interview with art historian Germano Celant. Eventually she made them into a wing, which she subsequently expanded into a full-body covering. ‘It became my second skin, not something I wanted to fly with,’ she explained. ‘I could caress someone with this wing, or somebody could be held inside it, becoming a bird-person.’

Specific, sensory, off-kilter (however sincerely meant, the image of a headless chicken is as comic as it is horrid): this description is the perfect distillation of Horn’s work, which frequently utilised animals and machines to figure out the absurdity of being human. Horn, who died earlier this week aged eighty, was a prolific creator of costumes, films, performances, kinetic sculptures and cacophonous installations, many of them concerned with the ticking pendulum swing between freedom and confinement.

As an art student Horn found unlikely and, by all accounts, miserable inspiration in a sanatorium, where she was sent for a year to recover from a lung disease she’d contracted while sculpting with fibreglass and polyester resins. It was a place where time moved very slowly: doctors counted stays in six or twelve-month increments; mandatory bed rest reduced the scale of her world to the corners of a room. There she sketched and sewed a series of body sculptures responding to her own loneliness and longing, imagining strange additions and enhancements to her limbs so that they might reach further, weigh heavier, find new functions and feel the strain of their own limitations.

The resulting work was marvellously strange. For Unicorn (1970–72), she placed a fellow classmate in a horn sculpted from wood, kept in place with the assistance of a set of tight fabric straps clipped around her naked torso. The girl was filmed – ‘albeit grudgingly, as she was very bourgeois’ – walking through forests and fields at 4am, the towering spike a ghostly white exclamation mark against the dappled landscape; head stiff beneath the protrusion like she was taking comportment lessons.

Art owes a lot to the sickbed: insightful essays, brilliant paintings, batshit ideas. Unicorn holds traces of Frida Kahlo’s The Broken Column (1994), a self-portrait of pain by an artist who intimately knew the boredom and frustration of convalescence – not to mention the erotic undertones of medical corsetry. Periods of illness or incapacitation demand an adjustment in scale, the sufferer sequestered from daily life (work, study, routine, other people) and confined to a space in which the internal world of dreams and desires must compensate for physical inhibition. ‘In isolation, you have this burning inside,’ Horn explained. ‘The imagination runs riot.’

Most spells of all-consuming sickness prompt only the most cursory self-reflection, if that. But for Horn, it set up a lifelong interest: what emotional freedoms could be found in being separated from the world and longing for what it held? Her body-sculptures weren’t just a way of reaching further into her own physical potential but reaching outwards towards others. Works like Finger Gloves (1972), which also featured in her video series Berlin – Exercises in Nine Parts (1974–5), turned the ends of her hands into spidery, trailing appendages that could caress a lover’s body or touch the opposite walls of a room at the same time. Her feathers exposed as much as they protected: works like Feather Instrument (1972), Cockatoo Mask (1973), Paradise Widow (1975) and the contraption featured in The Feathered Prison Fan (1978) were coy in their dance between entrapping and guarding the wearer – revealing their vulnerabilities either way. Wanting to be seen and touched is a very powerful urge, but so is wanting not to be.

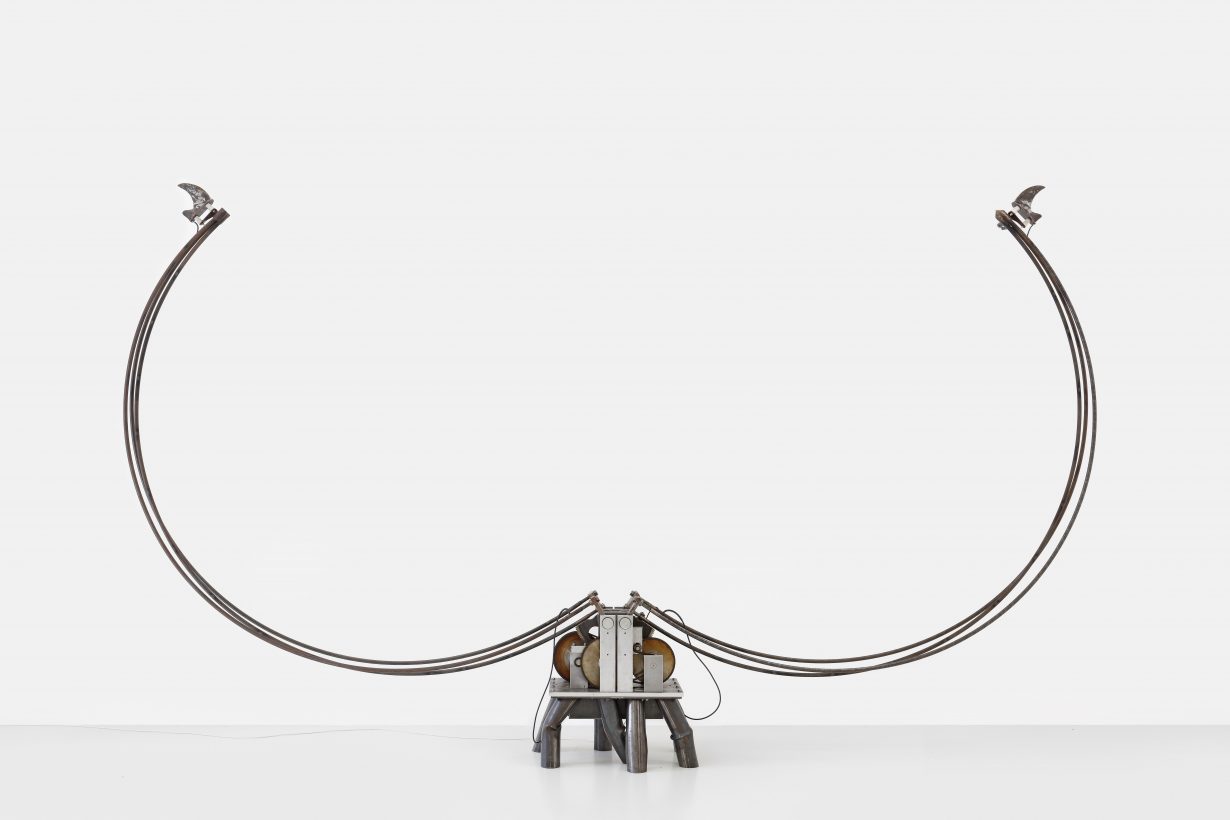

Over the course of her career, Horn’s surreal, intimate visions grew and mutated, turning from smaller-scale prostheses toward mechanical works and vast installations. The body was replaced with machines, which she saw as being just as real and fallible as any human. ‘I like my machines to tire,’ she told Jeanette Winterson in 2005. ‘They are more than objects. These are not cars or washing machines. They rest, they reflect, they wait.’ Her work High Moon (1991), which featured two Winchester rifles randomly spurting blood-coloured water and sometimes hitting each other, inspired Alexander McQueen’s SS99 show finale in which the model Shalom Harlow stood on a rotating platform, her enormous tulle dress sprayed with paint from two robotic arms. McQueen was a fellow dweller in paradox, his clothes – so often lambasted for their seeming violence and discomfort – shielding the women who wore them, rendering them untouchable.

Although McQueen is the most famous designer to pay homage to Rebecca Horn, echoes of her work reverberate elsewhere. The creations of Dutch haute couture designer Iris van Herpen bear a strong formal kinship to Horn’s work, although she has never made this connection explicit herself. Van Herpen makes kinetic dresses that look like they’re breathing or spinning on the body, often using the same palette of materials and references as Horn –feathers, butterflies, mirrors and alchemy. Her work is often described as futuristic, envisioning the hybrid human-machines it is imagined we’ll one day become. Yet even decades earlier, it was a label that Horn herself never countenanced, more interested in the relation between the past and the present than what lay ahead.

With Horn’s early works, it’s easy to suggest that they are one of two things: cumbersome (restricting movement, cutting the wearer off from others) or freeing (extending the body’s capabilities, opening new lines of communication). That same tension is frequently applied to the wider question of fashion and what we choose to wear. Does it inhibit or enable us? Is our clothing a source of limitation, dictated by social norms and uncomfortably tight seams, or something not only expressive of the self but capable of shaping and even transforming it? In truth, it can be both, with the same garment holding contradictory impulses.

In a 1994 interview, Horn said of the girl who performed her Unicorn piece that ‘by being turned into a prisoner, she freed herself inside’. This freedom could be understood quite simply as the loss of inhibition; the understanding that the world’s implied codes of conduct are easily broken. But it also represented a state of psychological and sensory change. Horn wanted to set off chain reactions, jolting both her performers and her audiences out of complacency and into deeper, more complicated assessments of themselves and the world around them.

When pressed by Celant in that interview of the previous year on her feathered pieces and their airborne potential, she pushed back. The ‘flying part’ was not relevant, she said. The idea of taking flight was, perhaps, too cowardly for her. Her work was not escapist. It never soared above life and observed it loftily from on high. Instead, Rebecca Horn was always down in the midst of it: observing our pleasures and tragedies, our warring instincts; rooting around in the blood and fibres and shed feathers, making something new for us to try on for size.

‘Rebecca Horn’ is at Haus de Kunst, Munich, until 13 October, and ‘Concert of Sighs’ is at Thomas Schulte, Berlin, 11 September – 2 November

Rosalind Jana is an art, fashion and culture writer