The artist’s project to identify her matrilineage advocates for a community so often defined as transient, as outside the bounds of history and place

‘The past is a foreign country’, goes the much-quoted line from L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between (1953). At least, it’s a country much of contemporary art has set its designs on exploring, challenging, reappraising or correcting. Indeed, for the artist Selma Selman, tracing 600 years into the past becomes as speculative an undertaking as it is into the future. Her exhibition 600 Years of Migrant Mothers at Kunsthuis SYB in the Netherlands is, on the face of it, a somewhat simple proposition: a multimedia description of the matrilineal line of her family. But, for a Roma family in the former Yugoslavia, it is hardly that simple: centuries of shifting geographies, archival gaps and erasures, rare and fragile records, all combine to frustrate the narrative.

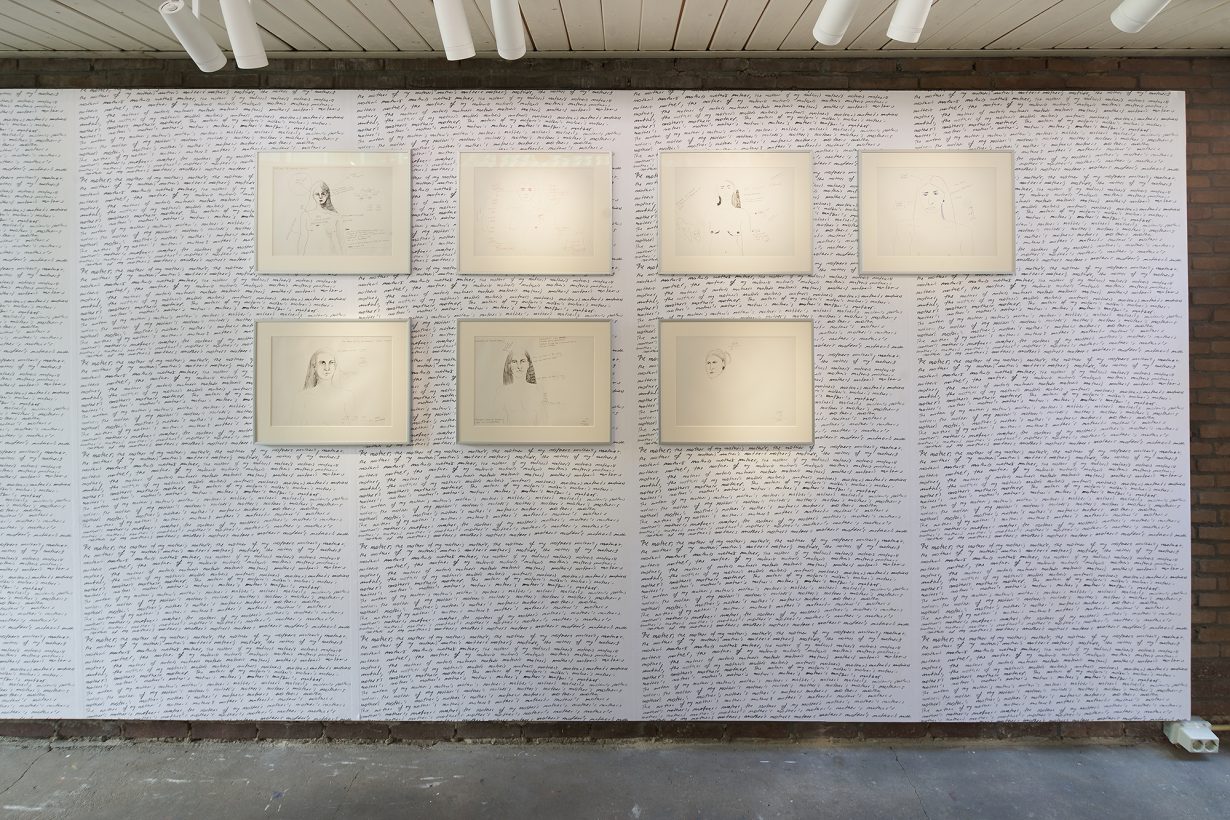

On the exhibition’s first floor, seven line drawings on paper begin to construct a timeline of Selman’s matrilineal genealogy. In each portrait of a woman from her family history, Selman annotates the figures with loose descriptions or comments suggesting information she has found or inferred about them. In each case, the available information remains inconclusive. The drawings sit against a wallpaper marked all over with the repeated phrase in black, ‘the mother of my mother’s mother…’, a textual loop enacting the attempt at constructing a narrative. Spread out across the same space, two sculptural pieces – titled 600 Years of Migrant Mothers (Part III and IV), 2025 – made from repurposed aluminium milk tanks carved into fragments. Each has been painted with a female figure, wrapping around the tank’s industrial shape; individual, unmistakably female eyes are dotted around the surfaces, with thick drops of paint cascading from their corners. Move around the room, and, at various angles, the painted works enter and disappear from view.

Tracing the generations of mothers who brought her into being leads Selman to Prishtina, Kosovo. In the first half of 2025, while expanding her research on her grandmother, she learned that her mother’s family once lived in Moravska, one of four neighbourhoods in the city known for its predominantly Romani population. Despite facing persistent biases and prejudices in the Yugoslav era, the Roma community in Kosovo nonetheless was known for its rich musical tradition. When Radio Television Prishtina began broadcasting twenty minutes of daily programming in Romani in 1986, considered the first Romani-language program in the world, many community members contributed to both the editorial work and the station’s in-house music orchestra. Some of this tradition surfaces in Selman’s The Wedding Feast (1998/2005), a 30-minute videowork documenting a Roma wedding from the artist’s extended family. Pieced together from grayscale footage found on YouTube, it’s hard to place in time. Where, and when, are we?

This – for a community so often defined as transient, as outside the bounds of history and place – is the emotional tenor of Selman’s work, and the Roma community she captures. Pleasant memories are infected by generational trauma, the lifetimes of social and structural exclusion by the societies they inhabit. That Roma people’s stories and histories are underrepresented is evident in the research of Blerta Ismaili, a junior scholar affiliated with Cultural Heritage without Borders, who repeatedly encounters dead-ends while uncovering even the most basic facts of Romani life in Prishtina. Her frequent correspondence with Selman from March to June 2025 – included in the exhibition as A4-printed pages, lists photos and links she found online – documents the people she met, the places she visited and the institutions she approached in Ismaili’s search for the grave of Selman’s grandmother, Ajša Bahtijarević. The inquiry yields little: we learn neither about her life nor about the location of her resting place. Selman’s video work I Couldn’t Find My Grandmother’s Grave (2025) depicts the city’s cemetery against the backdrop of new development projects, which wiped out the Dalmatinska and Moravska neighbourhoods. Filmed in an almost deadpan manner and devoid of human presence, the video unfolds through long, slow shots, dwelling on small, personal acts of commemoration and the subtle ways of maintaining connection with the dead. The camera lingers on graves from different periods and of various ethnicities, including those dating to the time of Selman’s grandmother’s death. The search as shown in the video proves futile. The Yugoslav Wars of the early 1990s displaced Roma communities across Eastern Europe, and by the end of the decade, following the 1999 Kosovo War, the Roma community in Prishtina where Selman’s mother grew up had all but disappeared.

Selman’s research into the past becomes a critical form of knowledge production, a way of reaching into the silences of institutional archives and the limits of public knowledge. On the exhibition’s second floor, The Visitors (2025) presents an installation of five unframed drawings of women, depicted from the front or back, lacking an eye or two, along with written statements on the walls accompanied by floral decorations covered with translucent curtains that at times reveal and hide them. Statements such as ‘Language changes day by day’ and ‘You always need to renew what is written’ serve to explore the limits of what is considered factual and to engage with that which is slippery. What enters written language is often vested with an air of permanence, while what enters the archive carries the weight of authority. Language’s mutability, on the other hand, renders many of its constructs unstable, and what is written must be revisited as language continually changes and forms new webs of meaning. Selman’s work makes you wonder why some historical narratives endure despite resting on the uncertain terrain of written language, while others, relying on communal systems of knowledge, prove more fragile. Thus she does not shy away from employing alternative forms of knowledge-making. Sharing the same room, the installation The Dinner (2025) presents a table laid with a cloth printed with multiple eyes and the repeated phrase ‘the mother of my mother’s mother….’ Around the table are seven containers of varying shapes and sizes, each filled with salt, which in Romani belief offers protection, here guarding a space for ancestral return and intergenerational learning.

That’s because within the institutions who protect the histories they create, Roma life is still confined to the margins. The Holocaust experienced by Roma and Sinti during the Second World War remains largely unacknowledged by common historical narratives, despite Yugoslavia having been positioned within the anti-fascist struggle. Thirty years on, the Srebrenica Genocide, in which around 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men were killed, continues to be met with denialist stances. More than 40,000 lives remain unaccounted for because of wars in the region. And so this absence invites other forms of investigation, which Selman – and I, in my research – turned to. To write about the Roma neighborhoods, I consulted a few oral history interviews. While publicly accessible, oral narratives and grassroots archiving initiatives are scarcely granted the same credibility as traditional archives, creating tension between what you know and what you can substantiate as fact. Selman’s work probes this slippage. In searching for her family, she learns not who they were, but why she may never know.

Erëmirë Krasniqi is a researcher and curator based in Pristina