An attempt to dismantle the glass walls separating the institution on one side and disengaged communities on the other

Horizontal connectivity

Amsterdam Dance Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands

10:30am, 26 Aug 2022

Forty students from all over the world gathered in Amsterdam to take a masterclass at Summer Dance Forever, one of the world’s largest street-dance festivals. Immediately everyone knew what to do when the instructor uttered the phrase ‘loose leg’, a foundational house dance move born in Brooklyn during the late 1980s and passed to me three decades later in a Hong Kong dance-studio. The joy of sharing the same move with a roomful of passionate strangers and inspiring each other with our own style was overwhelming. My body still remembers the magical feeling of experiencing intense freedom and connectivity at the same time.

‘Street dance’ is an umbrella term for many social dance styles including hip hop, breaking, popping, locking, house, waacking, voguing, and krumping etc. Many were originally born outside dance studios and mainstream clubs as a way to claim space and identity, as marginalised communities felt excluded or were actually denied entry. Over the past few decades, the ecosystems around street dance have been radically transforming: whereas first-generation Hong Kong b-boys (male breakdancers) reminisced about teaching themselves head spins outside the Hong Kong Cultural Centre based on memories of American TV performances, street dance studios have sprouted globally in the past decade, from chain operations in Shanghai shopping malls to outdoor car parks in Los Angeles during the height of COVID. International camps and festivals (including the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, which will introduce breakdancing as a medal event), reality shows, Instagram, and online-learning platforms have further catalysed the international exchange of major street-dance styles.

One may argue that the original underground nature of street dance has been diluted nowadays, but the popularisation of street dance also means that whoever is willing to groove can drop into a dance studio or take an online class. Often non-hierarchical and inclusive spaces, dance classes, sessions and even battles advocate sharing differences to nurture each other rather than fighting for resources. In Summer Dance Forever battles, for instance, teacher and student or judge and contestant often battle against each other, but they are equal once stepping onto the stage – in the final rounds, the audiences are the judges. The dancers’ playful interactions while competing against each other brim with love and respect, often ending with happy dances and deep hugs.

As street dance flourishes, fascinating stories also abound in the creases and folds of the transmissions and transmutations, in the nuances of each regional community, and in the idiosyncrasies of each dancing body.

Glass walls

Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Nice, France

5pm, 25 September 2022

I walked out of the museum and entered the courtyard, where two groups of Black teenagers were hanging out or dancing hip-hop against the building’s tall, reflective glass facade. I realised I had not seen more than five non-white visitors inside the museum during the course of the past three hours, despite the huge non-white population in France, a country in which this is the fifth-largest city.

In many cities around the world, I have noticed groups of people dancing outside major art spaces: be it Filipino domestic workers practicing TikTok choreography outside the Hong Kong Museum of Art, or house dancers training together alongside the Southbank Centre in London. Yet when I ask them how often they go inside to visit contemporary art exhibitions, oftentimes the answer is seldom or never. Those people are undeniably passionate about one aspect of contemporary culture, but feel distant from another. It made me think about exactly who art museums think they are programming for? Or, more broadly, what type of people feel welcomed and find resonance in contemporary art exhibitions? Despite the ever-multiplying claims by contemporary art museums around the world with respect to diversifying audiences, why do many still feel deterred by the social barriers of ‘high art’? Could art museums seek inspiration from the street-dance ethos to create more inclusive and dynamic experiences, and better reflect the increasingly fluid (both in terms of the dancing body and the migrating body) and diverse social contexts in which they operate?

Led by my growing fascination with street dance over the past three years, I began to investigate the intersection of street dance and contemporary art in an attempt to dismantle the glass walls separating the institution on one side and disengaged communities on the other.

Staking a Claim

Tramway, Glasgow, Scotland

3pm, 14 Aug 2022

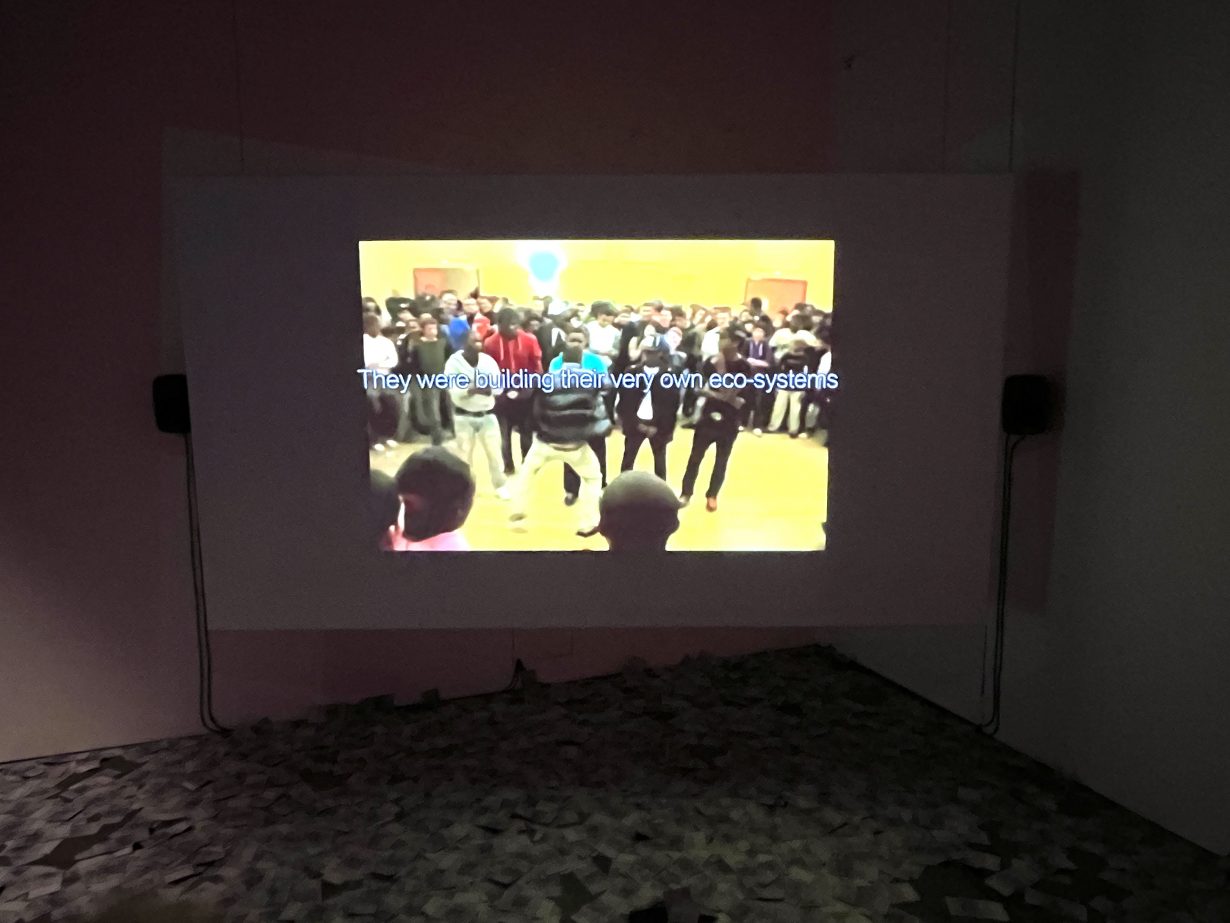

Entering the solo exhibition Gentle Battle, I was immediately captured by artist and DJ Christelle Oyiri’s video essay Collective Amnesia: In Memory of Logobi (2018–22). Born in France, but of Ivorian and Guadeloupean descent, Oyiri felt strongly about the erasure of the Black French contribution to culture, and started a longterm project Collective Amnesia to trace the forgotten histories of logobi, a street dance that appeared in university campuses in the Ivory Coast during the mid-1980s and then went viral among Black, working-class youngsters in the suburbs of Paris from the late 2000s to the early 2010s. It is not hard to imagine how the latter connected with the humorous expressions against social and political oppression in logobi. Building on the playful vibe inspired by bluffing and mimicking, dance crews would cypher or battle loudly in subway stations, malls, or on the street of Paris. Although I knew nothing before about the logobi dance or Ivorian life, I could not help but move to the music and connect to its uninhibited energy.

To highlight the radical nature of such public presence and its ecosystem in a country in which assimilation remains heavily institutionalised, Oyiri wove together a fiction of an amnesiac young woman wandering around the streets of Paris to retrace her past through art, sorcery, dance, and friendship with an immigrant. I was particularly struck by the protagonist’s dreamy walk among the frescos of the Palais de la Porte Dorée, a gigantic exhibition-hall built in 1931 to propagate the ideals of colonialism through a hierarchical depiction of races. How would I feel to be growing up in a city full of monuments with demeaning representations of my race? The juxtaposition of Palais de la Porte Dorée and logobi crews pinpoints the burning issue of how to decolonialise art institutions and open them up to marginalised communities, especially given the irony of the Palais de la Porte Dorée becoming the home of France’s National Immigration Museum since 2007.

After grooving alongside the video installation, I meandered around mirrors, a four-poster bed, an elephant tusk hanging from the ceiling, and a karaoke booth… The dynamic exhibition space entices and choreographs the audience to constantly shift our posture to navigate capsules of underrepresented cultures and portals to resilient ecosystems, shedding light on how the cultural and political battle gently displays itself through our bodies, our music, and our dance.

If we follow Oyiri’s steps and continue to shatter the pristine glass walls between street dancers and art museums, what else will we find in the cracks and the gaps? I could imagine a myriad of dances and stories around cultural and gender diversity, diasporic experiences, alternative modes of communing and solidarity, embodied knowledge, and how to proudly claim one’s space.