For art, Ilê Sartuzi removed a coin from the London institution’s display

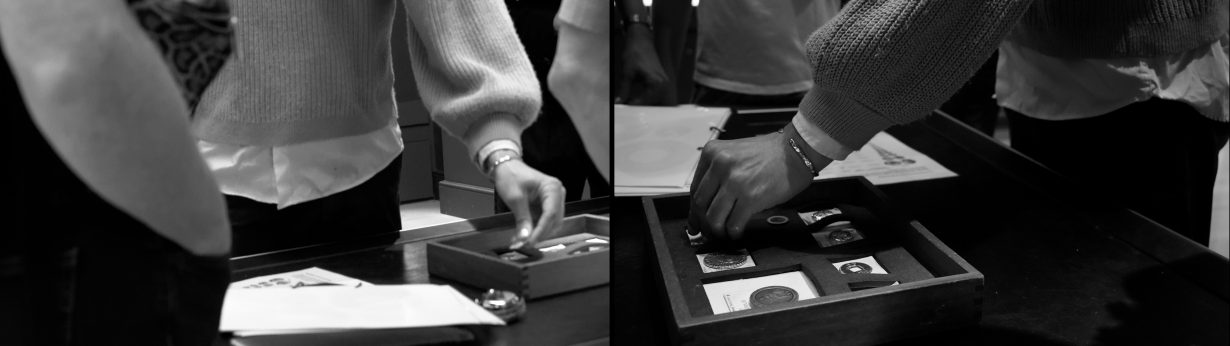

On 18 June, a little before lunch, a young Brazilian man with a thick beard walked into Room 68 of the British Museum and stole an ancient coin. Artist Ilê Sartuzi had planned his heist meticulously, staking out the display of seventeenth-century currency over twenty visits spread out over months, identifying the English Civil War-era silver coin that he would take and commissioning an exact replica. Carefully, he mapped the shift patterns of the volunteers who staffed the museum’s ‘collection handling sessions’ in which visitors can hold objects. He practised the sleight of hand that he would deploy, the fake coin pressed into the palm of one hand, fingers slightly bent over as a shield. He employed a couple of accomplices, used for distraction and to block points of view. When the time was precisely right, he picked up the real coin, crossed his palms, and replaced it on the handling mat with his fake.

He made a getaway from the gallery swiftly, but without any undue haste that might draw attention to his crime. As he arrived at the stairs leading down to the main entrance hall of the museum, his pace quickened. It was as if he couldn’t quite believe he had got away with it and didn’t want to jinx this perfect snatch by dawdling. He did have one final job however. Just before passing through the exit to the museum forecourt, Sartuzi slipped the apprehended coin into the collection box of the institution, the ancient metal landing softly among the new notes and shiny bronze of the modern money. With that he disappeared outside, threading through into the crowded streets of London.

Sartuzi’s ‘theft’ – though, liaising with a lawyer from the start, he was reassured that no such theft had taken place, as the object never left British Museum property – has been minutely documented in hidden-camera footage, 3D renderings and further replicas of the diamond-shaped coin, in the artist’s current MFA show at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He’s been teasing me with the idea for a while, though never fully explaining it. The artwork, which Sartuzi has titled Sleight of Hand, comes at a tricky time for the British Museum: last summer a curator in the Greek and Roman antiquities department was sacked on suspicion of stealing some 1,500 objects from the storerooms (at least 626 pieces have since been recouped); the then-director Hartwig Fischer stepped down shortly after the scandal broke, and his successor Nicholas Cullinan is only a few weeks into the job.

Sleight of Hand is steeped in questions of conquest and restitution: Sartuzi comes from a country that was colonised; he ‘stole’ – an English object, no less – from the British Museum, long a symbol of imperialism with an infamy for its array of historically thieved items. It is an act of retribution, a commentary on custodianship and a moment of protest combined. Yet the language the artist uses in his video documentation to describe the heist elevates it beyond mere stunt. He refers to the volunteer manning the handling session as a ‘magician’, he talks of taking the coin as a trick, he the trickster. Indeed, in Brazil the trickster role is mythologised as Saci, a folkloric character in the form of one-legged former enslaved person, conceived amid the suffocation of colonialism as a rebellion against a rigid caste system. Sartuzi did no great harm, but his act is a cause of irritation: in the British Museum’s response, a spokesperson lambasted the work as a ‘disappointing and derivative act that abuses a volunteer-led service’ (after all, there’s nothing more annoying than losing money). But his vanishing trick raises a wrinkle in the world system embodied by the universal museum, the hegemonic recording and presentation of history as evidenced by records of ownership. It’s a small act of chaos in which not just the coin, but the assured order of the world, might disappear, given the right distraction.