A century after the first iteration, these public-private cameras have changed the way we think about photographs

There are various types of cubbyhole in which one can sequester oneself while still, technically, being in public: the toilet cubicle, the dressing room, the confessional, the photo booth. All are designed with the understanding that some things must be shielded from view, though this courtesy doesn’t always extend to the feet. The reasons for privacy may be practical or spiritual, but a shut door or drawn curtain creates an immediate intimacy, a space in which the face, hidden from passing eyes, can drop its public mask.

When Anatol Josepho opened the world’s first automated photo booths on Broadway and 51st Street in September 1925, his Photomaton studio attracted 280,000 customers within the first six months – its three booths staying open each day until 4am. Although attempts to create an ‘automatic’ camera date back as far as the 1880s, it was Siberian immigrant Josepho who eventually won the innovation race. As detailed in Näkki Goranin’s American Photobooth (2008) Josepho had been obsessed with cameras since he was a boy living in Omsk, where he first encountered the box Kodak Brownie. Like many of his generation, the appeal of the camera lay not only in its artistic potential but its technical possibility. For the machine-mad, a novel technology, once learned, invites improvement. Following years of study and travel – including sojourns to California, Shanghai and a return to a much-altered Siberia after the invasion of the Red Army – Josepho, back in New York aged thirty, raised $11,000 dollars for the creation of a machine he’d been designing and refining for more than a decade. A year later he would sell the patent for a million dollars.

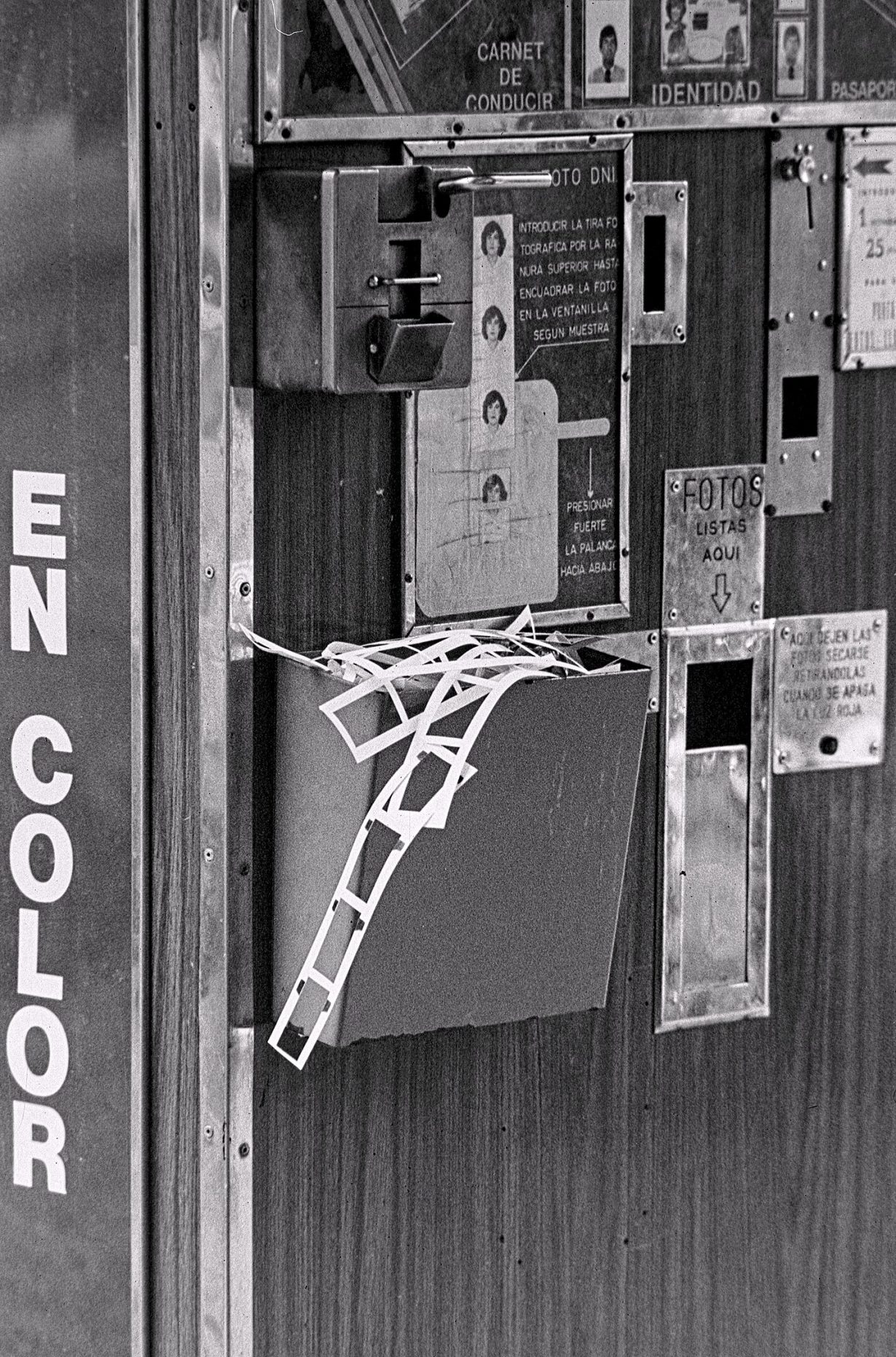

This year marks the centenary of his invention. The occasion has yielded various events, exhibitions and projects centred on the photo booth, many of them emphatic on the unusual magic of this little half-public, half-private box in which coins are parted with (or now, more likely, a card is tapped) in exchange for a strip of photos, each the record of a quick 3-2-1 and a decision made about expression, pose and so on. These days the photo booth must mount fresh arguments for its appeal: the Polaroid and its digital successors made it possible to print photos on the go; the lighting in a photo services shop produces more flattering passport photos (or at least ones less likely to fulfil Barthes’s 1979 proclamation that ‘the Photomat always turns you into a criminal type, wanted by the police’); and the smartphone turned us all into simultaneous photographer and subject, giving us the ability to study – and capture – ourselves with such regularity that we have all grown overly familiar with our own faces.

For a while it seemed that the photo booth might get by on pure kitsch factor, riding the post-Amélie, analogue-curious current of the late noughties and early 2010s, a time that can now be read as the first wave of reaction to the increasing encroachment of the digital world. But now that mode has itself become dated (other than in the wedding industry, where the photo booth is still doing a roaring trade, complete with hats and props). This is not an age of whimsy. We are suspicious of anything too nostalgic or sentimental, too straightforwardly earnest. And yet, there is something in the physicality of the booth that continues to draw people in, beckoning them to sit down and contemplate themselves.

Recently I asked a friend whether she thought the photo booth still had the capacity to be intimate, to be a place where one could do something interesting. She told me that when was eighteen she went to Florence and spent her week there seeking out the city’s photo booths. Whenever she found one, she would make a friend stand guard outside while she ducked in and stripped, only the curtain standing between her and public indecency. She still has the photos. The way she described this, there was an element of the illicit – the pleasure of disclosure – but also a kind of innocence. An image could be taken, processed and spat out into the world not just spontaneously, but quasi-anonymously. In this respect, the old rumour on their emergence that photo booths had tiny men hiding inside of them doing all the work suggests not only an early machine-suspicion, but a fear that the premise was too good to be true. A camera with no operator (and, these days, at least with the old-fashioned booths, no store of digital data) is neither virtuous nor judgemental. It takes pictures, then gives them back.

This is why the photo booth’s great gift is its fixed angle. You can move around the frame – stand up, crouch down, turn your back on the lens embedded in the wall – but it does not possess the potential flattery or endless decision-making of a handheld device. The location is also fixed, becoming part of the geography, whether the terrain is a shopping centre, a train station, a street corner or an art gallery. This is not the camera as a roving eye but a set vantage point: installed out in the world, waiting for visitors to move within its reach and leave again, memento in hand.

Over the last century, many artists have toyed with the photo booth, struck not only by its formal constraints but its interesting relationship with duration, repetition and the tension between revelation and roleplay. When the machines first arrived in Paris in 1928, André Breton turned up with a phalanx of his fellow Surrealists, intrigued – as good automatists would be – by this fast-moving, operator-less camera. The photo booth does not give you long to prepare. It may just catch you unawares. For Breton et al, the machine’s symbolic appeal may have outweighed the artistic merit of the resulting images, which are quite prosaic. For later generations of artists like Andy Warhol and Richard Avedon, hyper-attuned to the power (and power exchange) of the image, they were spaces in which to toy with convention.

Avedon shepherded celebrities into them for an Esquire commission, ceding his place as the God behind the camera in favour of some light art direction from beyond the curtain. The images have a wonderful spontaneity: in one, Truman Capote leans over Audrey Hepburn’s shoulder, cigarette dangling from his lips. Warhol turned his photo strips into mini filmic experiences, populated by costumed characters and gestures worthy of silent cinema. But the best work that has emerged from the photo booth has been quieter, less interested in the adoption of a persona than the steady, slow and, yes, intimate, documentation of time, such as Bern Boyle’s daily self-portraits capturing himself for a year after his AIDS diagnosis. Such work speaks not only to the photo booth’s unusual frankness, itself a product of its indifference, but its democratic gaze. Anyone can use it, whether for a one-off image or a steady study of the self, in all its incremental changes. All you have to do is sit down, press the button and wait for the countdown to begin.

Rosalind Jana is an art, fashion and culture writer