Recent reviews have called the artist an ‘idiot’, something Finlay might have quite enjoyed

As a poet invested in the etymological and sonic slippages of words, Ian Hamilton Finlay might well have taken pleasure at being called an ‘idiot’. The word, from the Ancient Greek for ‘one’s own’, would have gone well in one of Finlay’s concrete poems, meditating, perhaps, on his uncompromising ‘idiosyncrasy’. If Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones’s recent review of Finlay’s show at Victoria Miro is anything to go by (‘Finlay was an idiot’), the Scottish artist still has the power to infuriate those provoked by his ambiguous take on difficult histories – from the Roman Empire to the Third Reich – and their entanglements with aesthetics. The show is one of eight across Europe and New York celebrating the centenary of Finlay’s birth, their collective title alluding to his way of invoking associations between de- and recontextualised words, images and objects that often have a militaristic and neoclassical tenor and tickle the imagination without resting on any singular meaning.

At first glance, the works on the ground floor ache with positivity. If only life were as idyllic as reading, in a wall-mounted blue neon, A, E, I, O, Blue (1992), or circling a stone Tuscan column – reduced to the personable height of a doorway – with Blue Waters Bark (1999) engraved in red, while one mouthed these vowels and words. That something more sinister might be at play is implied by Flat Top / Tombstone / Altar A Place / For Light / To Land (1987), a small platform of bricks sandwiched by Portland stone, the versified title divided in two and carved in neo-Roman typeface on opposite sides. The ambiguous first tercet – ‘flat top’ is also military slang for an aircraft carrier – is mitigated by the sunshine possibility of the second, the overall sentiment either uplifting or unnerving depending on which way you walk round.

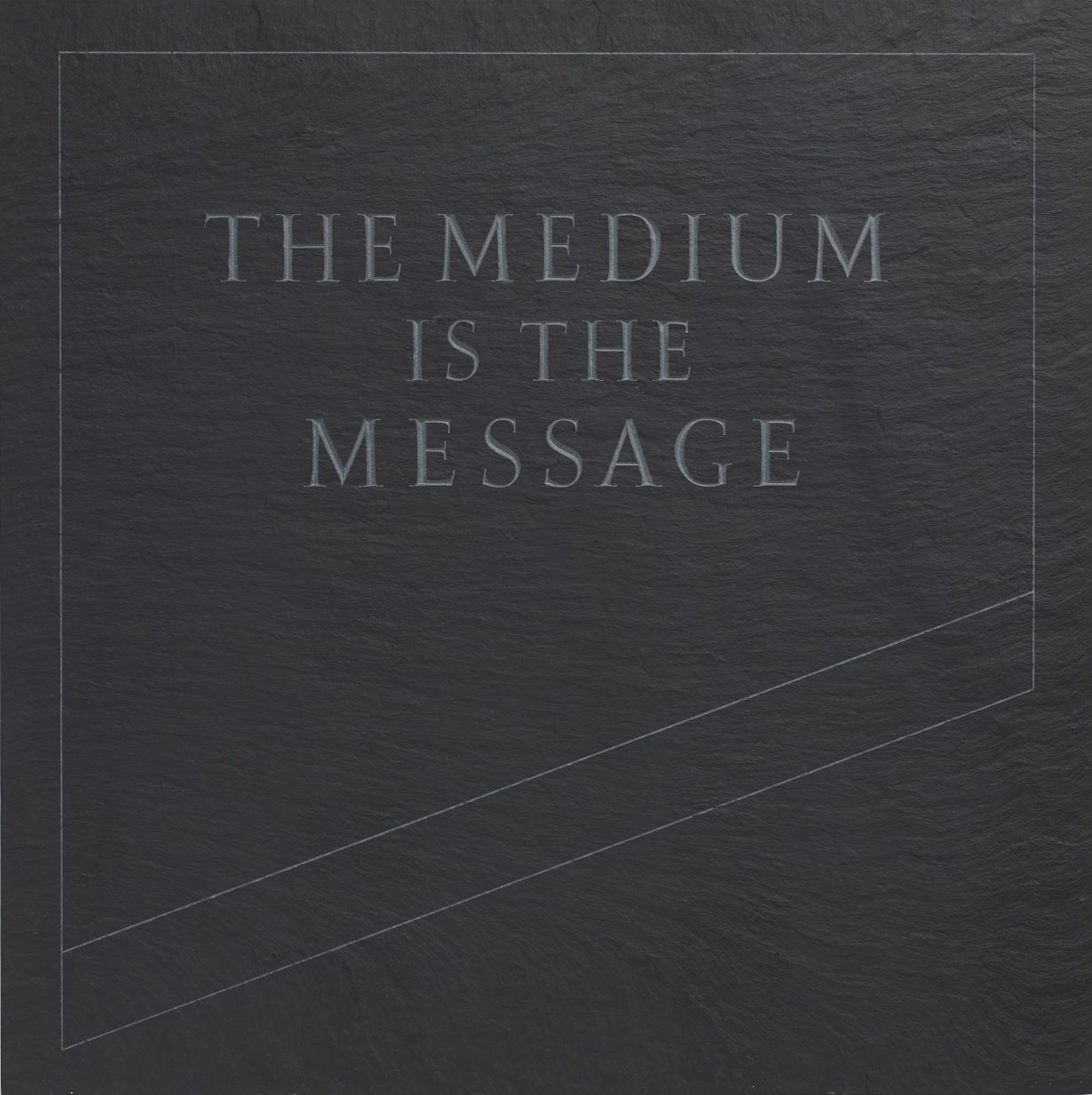

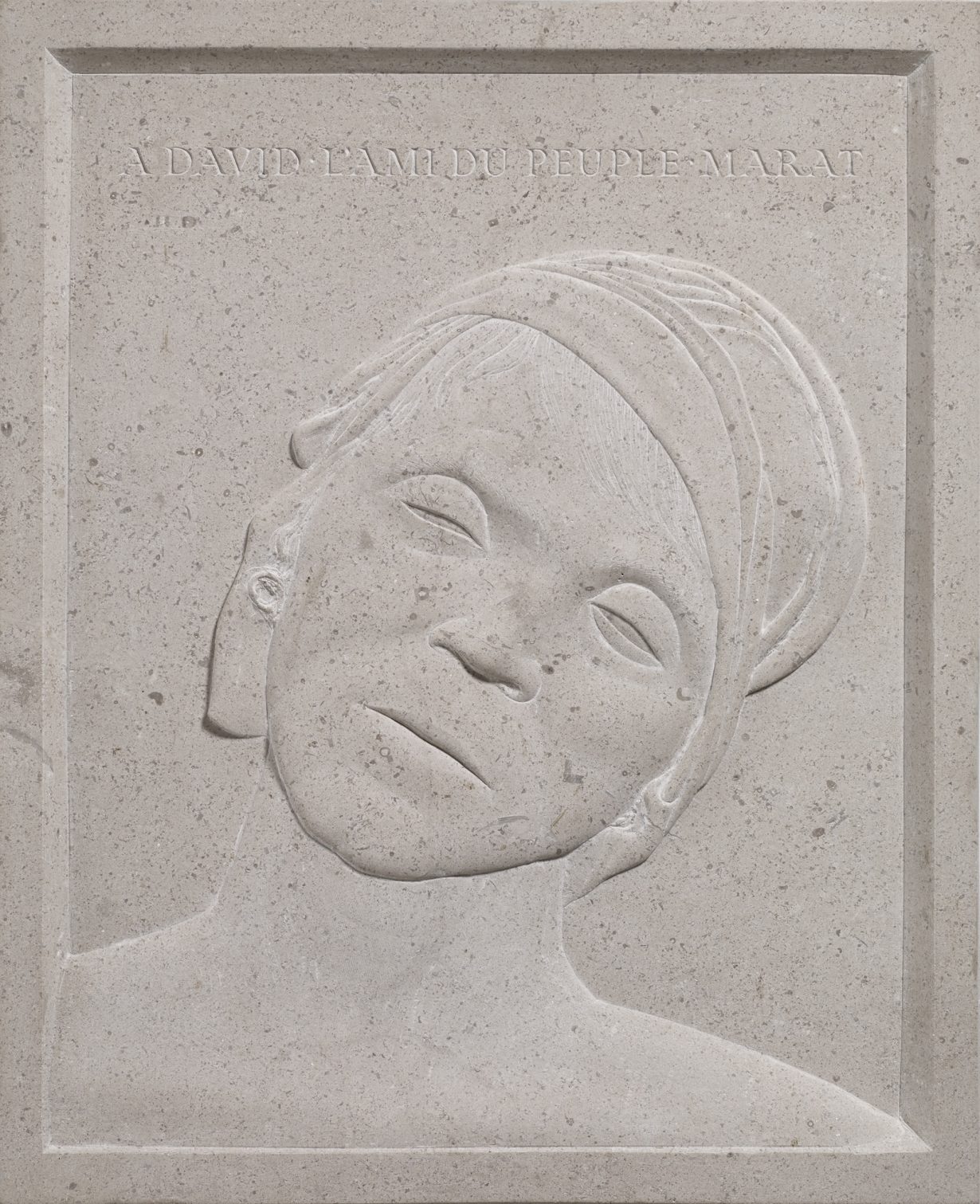

The gallery upstairs foregrounds Finlay’s preoccupation with the French Revolution, work long lambasted by critics, most recently by Jones, as a celebration of the bloodshed of the guillotine. The Medium Is The Message (1990) is a rectangular slate slab with the title engraved within a depiction of a slant-edged blade, an emblem wittily, if disturbingly, conflating subject, semantics and form. (The phrase is theorist Marshall McLuhan’s famous 1964 aphorism about electronic media.) The stone relief Head of the Dead Marat (1991) reinvents Jacques-Louis David’s famous 1793 painting of the murdered revolutionary, cropping the head and turning it upright (as if resurrecting him in a portrait), and replacing David’s dedication ‘à Marat’ with ‘à David’, in acknowledgement of art’s role as a ‘medium’ of history (Marat has, after all, become synonymous with David’s painting). To dismiss these works as one-sided apology is to shy away from the sublimation of violence in classicism, which threads through, among others, Ovid’s many rape scenes, the heroism of the French Revolution, the insignia of the Third Reich (another one of Finlay’s interests, maligned despite, or because of, its frightening pertinence today) and their tentacular legacies.

In the middle of the room is 12/1794 (1994), a circle of ceramic, tricolour-striped candleholders on high stools, each candleholder painted with the name of a French revolutionary – such as Robespierre or Saint-Just – as if conjuring their spirits. Yes, they were violent men, but also crucial to the formation of modern liberal democracy (Robespierre was an anti-colonialist who fought for the abolition of slavery). Their resurrection here is not to promote violence, but to confront one of history’s many awkward, enduring and maybe even a little maddening paradoxes.

Fragments at Victoria Miro, London, 30 April – 24 May

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.