According to T. J. Clark’s new book, to understand Paul Cézanne is to grasp his discontinuity – and enduring modernity

Ten years ago, art historian T. J. Clark, reviewing a show of Paul Cézanne’s Card Players series (from the early 1890s), announced that the French painter ‘cannot be written about any more’. It went on to be his most-cited (and most-criticised) remark. In his new book Clark explains what he meant. Cézanne, a painter known for his still lifes and landscapes, is generally regarded as among the most significant modernists. Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse revered him. Clement Greenberg declared him ‘the most copious source of what we know as modern art’. But, Clark argues, such judgements were driven by assumptions – an ‘overweening faith in Art’, a belief in art’s ‘access to Truth’ – that are alien to us today. Clark wants us to recognise this historical discontinuity, to give us a sense that to understand Cézanne is to grasp this discontinuity. Cézanne can be written about provided that we do not assimilate him to the present.

But (and this is the paradox that Clark wants to inhabit) Cézanne continues to speak to us all the same. He is historically remote, but also our contemporary. And the basis on which we might understand him – or fail to – hasn’t changed: the experience of modernity. Cézanne’s work embodies knowledge of what it is to be modern, the book argues. This knowledge is mostly negative. It is a peculiar kind of not-knowing characterised by ambiguity and contradiction.

These values are exemplified by the formal structure of Cézanne’s paintings. Take, for instance, the apples in the famous still lifes. They are peculiarly magnified. They seem to be rolling off their plate right into our hands. And yet their location in pictorial space is uncertain. They are available, ready for the taking, but we don’t know ‘where to have them’, Clark says. The resulting disorientation is a specifically modern feeling.

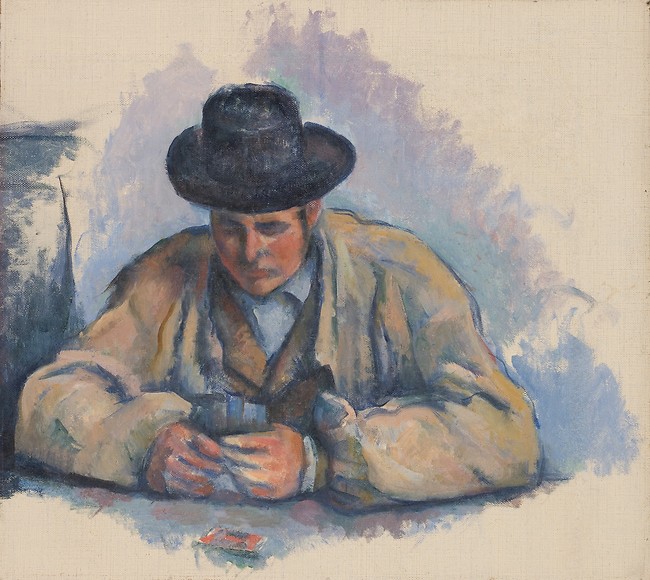

Clark is not the first to highlight this aspect of Cézanne’s work. Greenberg put Cézanne’s ‘unfading modernity’ down to the ‘problematic quality of his art’; Roger Fry felt himself ‘reduced to negative terms’ when tasked to put words to his paintings. Some of these words (used by Fry and Clark alike) are ‘disquieting’, ‘unnerving’, ‘uncanny’ and ‘sinister’. However, Clark distinguishes himself from his predecessors through his sheer insistence on Cézanne’s – and modernity’s – negativity. Across the book’s five chapters – on Cézanne’s apprenticeship to Pissarro, his still lifes, his landscapes, the ‘card players’ paintings, and the legacy of his work in a canvas by Matisse – Clark errs on the side of modernity’s failure.

In the first chapter, we find Clark meditating on the feeling of homelessness conveyed by Cézanne’s landscapes. Chapter two interprets Cézanne’s treatment of proximity and distance as an attempt to come to terms with ‘the new form of the object-world’ – that is, the commodity form. In chapter three Clark mobilises the materiality of the brushstroke against the notion of ‘the aesthetic as a moment of adequacy of form to content’. Chapter four makes a case for the peculiarly modern (as opposed to reactionary or revolutionary) quality of Cézanne’s peasant card players. In the final chapter, Clark reflects on Matisse’s aestheticism, arguing that the autonomous artwork, while self-enclosed, registers social contradictions all the more acutely (Clark is channelling Adorno).

The analyses, while often scintillating, are also relentlessly formal. What’s lacking is the texture of a specific historical period. One gets a little apprehensive when references to cave painting, world history and metaphysics start piling up towards the end of the book. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Clark contravenes his own call to honour Cézanne’s historical specificity. He experiences Cézanne’s paintings as the very embodiment of modernity – understood as an irresolvable contradiction, an ‘interminable to-and-fro’. But it has to be asked whether this is Cézanne’s modernity or ours. Clark often has Cézanne ventriloquise the disappointed hopes of our own (post-)postmodern era. What ends up dropping out of the analysis is an appreciation of the utopian dimension, art’s promise of happiness, which should not be ignored for its period flavour.

If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present by T. J. Clark. Thames & Hudson, £30 / $39.95 (hardcover)