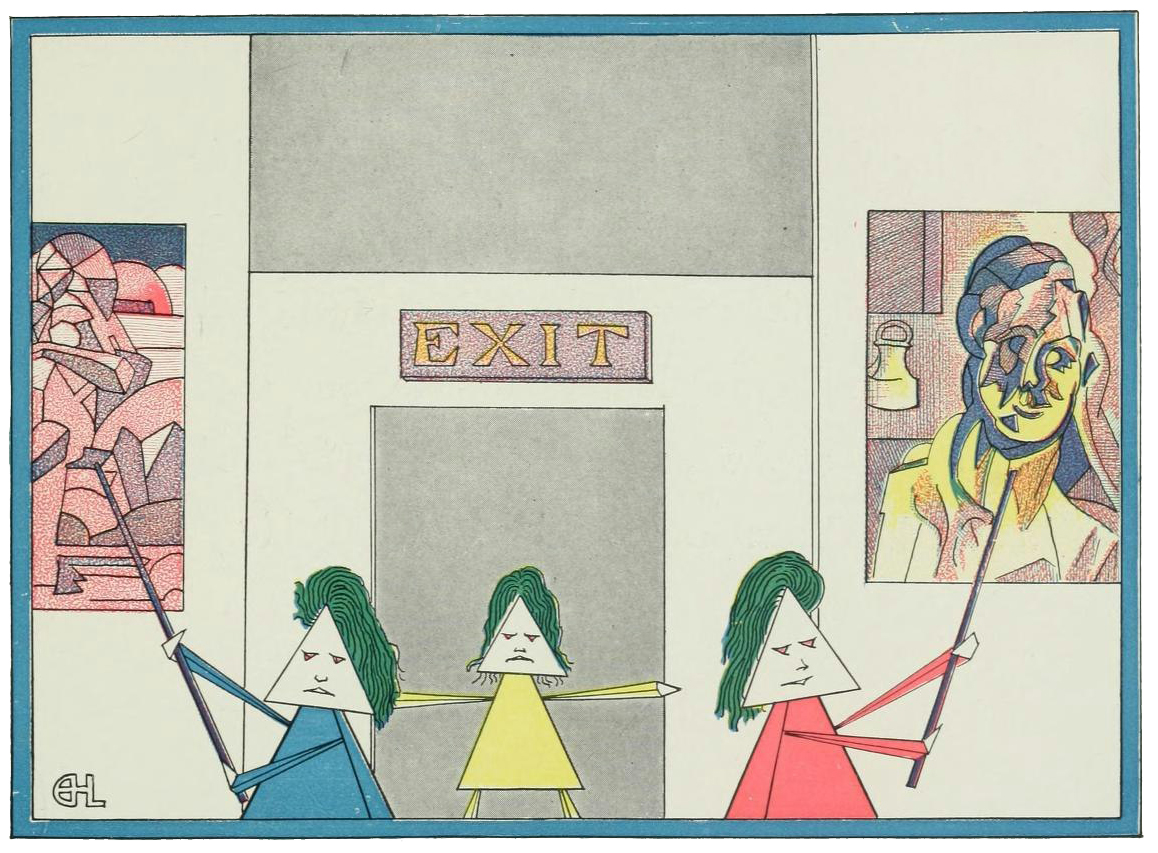

State funding tends to come with strings attached, trapping arts organisations into bureaucratic policies. So who wants it?

In the postwar era, spending public funds to support the arts has usually been seen as a good thing. In European social democracies it has played a major role in shaping the public’s access to the arts – in England, Arts Council England (ACE) spends over £548 million each year on funding organisations, artists and arts projects – and while in the US the arts have been largely bankrolled by private philanthropy, the government, through agencies such as the National Endowment for the Arts, has for decades put money into the pockets of artists and arts organisations. When governments have made cuts to arts funding, artists have usually complained.

They don’t usually complain about receiving subsidy. But in March something unusual happened: Wigmore Hall – a prestigious classical music venue in Central London – announced that from 2026 it would forego the £344,000 annual subsidy it currently receives from ACE. The problem, according to its director, John Gilhooly, was the ‘onerous bureaucracy’ of the reporting on audiences and activity that ACE demand of the arts organisations that it funds. But behind those requirements is ACE’s funding strategy, ‘Let’s Create’, drawn up in 2020. The strategy ties funding to organisations fulfilling commitments to, among other things, diversity and environmental agendas. Arts organisations must, for example, ‘agree targets for how… the work they make will reflect the communities in which they work’, while being expected to promote ‘the need for environmental responsibility in the communities in which they work, through their partnerships and with their audiences’. It’s an approach that emphasises what are, in effect, social and eventually political agendas, while seemingly less interested in traditional artforms or questions of artistic value and excellence – issues still key to the culture of classical music. Strangely, the term ‘the arts’ appears a handful of times in a document whose preoccupation is with a more diffuse notion of ‘culture and creativity’, prioritising activities that focus on audience access and participation.

Regardless of where one stands on the value of diversity or environmental agendas – in the ‘culture wars’ continuing to rage between left and right, or between progressivism and populism, these have become increasingly fractious and contested issues – it’s obvious that particular political outlooks have imposed themselves on how the arts are funded, to the point where arts organisations are now questioning whether the money is worth the ideological strings that are attached. Public funding for the arts was always sold as independent or ‘at arm’s length’ of political agendas, but this is no longer the case (if it ever really was), and the issue cuts both ways. In the US, the Trump administration’s recent cuts to the National Endowment for the Humanities, and in the executive order targeting national institutions such as the Smithsonian – highlighting what it sees as the predominance of ‘divisive ideology’ in the arts and cultural life – reminds us, if nothing else, that state funding for culture was never free of the ideological priorities of funders.

Nevertheless, if these different cases appear opposed – state funding being cut by a right-wing administration on political grounds, an arts venue refusing state funding because that support is conditional on it achieving the funder’s increasingly politicised objectives – the current controversies tend to exaggerate the significance of public funding in the wider arts-funding economy. While the Arts Council’s sour response to Wigmore Hall’s success in raising a £10m endowment fund was to do with the venue being ‘in a wealthy part of central London’, the fact is that, in the UK, ACE funding has diminished as a share of arts organisations’ revenues generally: according to its own survey, ACE subsidy now accounts for only 20 percent of organisations’ revenues (and even less in wealthy London). It’s not surprising that the policy (or political) demands ACE makes of its clients should start to seem to some organisations disproportionate to what it contributes.

If public funding is likely to be constrained in the future, Wigmore Hall’s fundraising suggests that arts funding will shift more towards the US model, where a greater reliance on commercial and philanthropic income has always been the case and private philanthropy dwarfs that of the state. The NEA had a budget of $207m in 2024, but this is a small fraction of revenues of the US’s nonprofit arts sector, which in the 2021 tax year recorded revenues of $41 billion, and had assets of over $170 billion. The endowment model (a major element in the finances of US arts institutions) will likely look increasingly attractive; London’s Tate, itself currently in some financial difficulty due to reduced audience numbers post-COVID, has been pursuing the fundraising of a ‘permanent endowment’.

What that might entail is greater artistic independence for arts organisations; it might also mean that they become more aligned with the cultures and priorities of their increasingly private benefactors, or the particular interests of their audiences. How these shake out in the polarisations and divisions produced by the ‘culture wars’ remains to be seen. It will probably mean a mix of all three, which might risk turning the arts into a world of increasingly niche interest groups and organisations. But it may also foster a greater plurality of perspectives and a greater focus on artistic work itself, and push to include bigger publics rather than be beholden to the changing whims of state policy, or the fragmented audiences defined by adherence to one or other political culture. Either way, the old model of state funding for the arts is on its way out, and a new relationship between art, funding and the public is slowly taking shape.

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.