In a Bright Green Field foregrounds young artists from Greece and Cyprus imagining a new future for the region

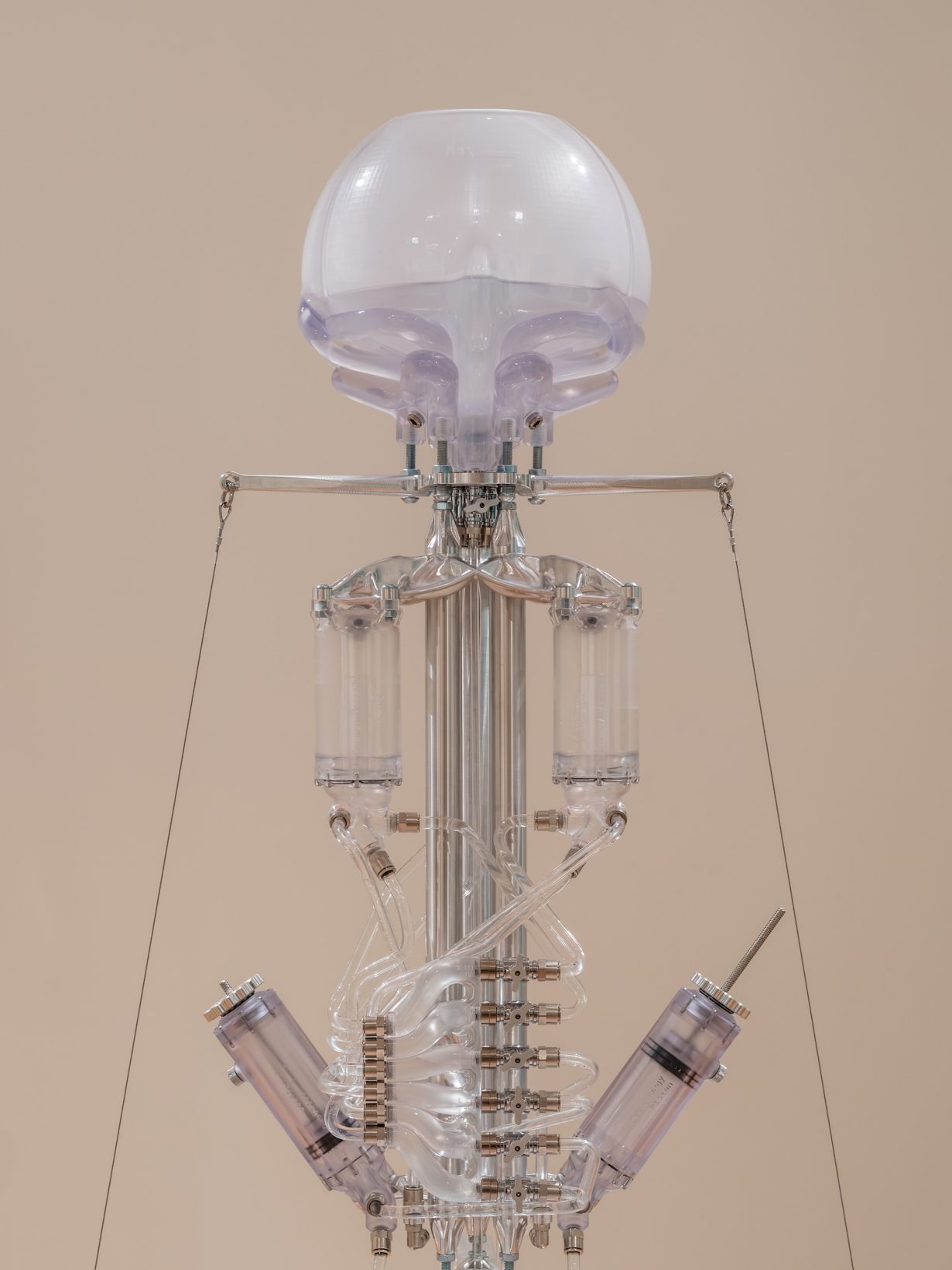

In a Bright Green Field features 29 young artists from Greece and Cyprus: a generation who’ve grown up since the Greek debt crisis of 2008. Not surprisingly, its central theme is the desire for change. Much of the work explores, as strategies for generating a different and more communal tomorrow, an understanding of local, peripheral histories and a relation to the natural world. Byron Kalomamas’s if you want to know about Change, first look at rivers (2025), for example – referencing the Phillips Machine, a 1949 device for modelling economic workings using hydraulics – is an obsessively fine-detailed apparatus featuring ligamentlike machined parts, circulating water in wave patterns visible through a clear acrylic basin. The flow is controllable by the viewer. Danae Io’s Dial II (2025), meanwhile, is a sort of proto-cinema machine, a revolving maquettelike carousel in which mirrors reflect an external ring of telephone cards featuring a painted view from an Athenian hill, made during the 1830s–40s by Scottish lawyer/amateur artist James Skene. The image, depicting a sparse Athens freshly freed from Ottoman rule, whiffs mildly of empire – whether the recently ended regime, or the empty expanse calling for a new ruler. The work, nevertheless, draws loose poetic connections between the colonial gaze of the depicted period and Greece’s more recent crisis and status as, arguably, a debt colony of the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF.

Look up into Raissa Angeli’s 1989 (2025), a wall-mounted, polished-steel structure, and you see the layout of the artist’s childhood house in Nicosia, dotted with ciphers of lived-in-ness, eg cartoon stickers. Underneath hangs a T-shirt imprinted with a bewildering photograph featuring two men (one toting a gun): Angeli’s journalist father and Abdullah Öccalan, then leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party or PKK, a separatist organisation founded in 1978 to protect Kurdish minorities in Turkey. Printed on a garment suitable for a pop fan, it’s a relic of romantic teenhood, now part of a dreamy constellation of losses and changes: the homestead, Angeli’s parents’ youth, the PKK (recently dissolved), Cyprus’s evolving geopolitical identity. Similarly architecture-driven, and made amid the financial crash, is Marina Xenofontos’s Ideology (and conviction) was modified with pragmatism (2012/2025): two walls form a corner, clad with reclaimed cast cement tiles dating from the start of the previous century and interspersed with mirrors. It feels like a building-site set crosshatched with cosmic portals, pointing at once towards past and future, stars and proverbial gutter: Schrödinger’s cat could live here.

That animal might also be at home in Damianos Zisimou’s ghostly monochromatic fieldscape paintings. Based on renderings of historical queer painters’ paintings of flowers, they’re steeped in viscous colour tonal swirls and washes: one series moves from carmine to deep magentas, another from Prussian blue to cobalt greens. This haze of nebulous pigmentations creates a casual illusory depth, but the paintings remain hollow and unpopulated, like backdrops for possible scenarios. The original imagery, suggestive of tenderness and desire, is coated in a fog of uncertainty, the monochrome spectrum reminiscent of the recent wildfires tinting sunsets in a toxic single colour frequency. Against this poetic but very real anxiety about the future, there’s the partial remedy of a sense of supportive community, offered by the eponymous subjects of Konstanza Kapsali’s 2023 film Elsa & Olga. Immersed, in autumn, in the cooling waters of the Cretan Sea, they tell each other – and us – that they’ll keep swimming into the winter, and engage in a sunset-lit aquatic chat about the antics of ageing, the cyclicality of the seasons, promising resilience together, against the coming winter’s cooling water. Kapsali’s edit manages to make us feel disarmingly like we’re there with them, wrapped in the interconnecting ageless egalitarianism that being immersed in the same body of water feels like, in a communal activity that feels older than that sea itself. Arguably, everything begins and ends with water.

In a Bright Green Field at Benaki Museum, Athens, 12 June – 13 September

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.