From 2007: As the great filmmaker rolls back his work, Skye Sherwin asks: is David Lynch a great artist?

In 1990 Parkett ran the feature ‘(Why) Is David Lynch Important?’ In it, various cultural commentators, artists, curators and other thinkers waxed lyrical on the significance of the director’s films. There was mention of his achievements as a ‘stylist’, of ‘clip-aesthetics’, the MTV generation mentality and, of course, his impact on Hollywood and, by extension, global culture. By 1995 David Foster Wallace was able to remark that Lynch had reached a point at which he could be defined in his own terms; he had achieved adjectival status: he was simply Lynchian. And to many he is one of the ‘great artists’ of our times.

This month a major show of Lynch’s artwork, The Air Is on Fire – encompassing painting, photography, drawings, film, animation, installation and sound art from the 1960s to the present day – opens at the Fondation Cartier, in Paris. At the same time, a new movie, Inland Empire, is being released in France and the UK, following rapturous reviews in the States, where critics declared it to be his best work since Eraserhead (1977). What better time, then, to revisit the question of his importance, the claim that he is one of our great artists?

On a day of blazing heat, even by LA standards, Lynch sits in his studio above ‘the compound’: two beautiful modernist constructions of grey stucco and glass. One is his home; the other houses the offices of his production company, Asymmetrical Productions (as well as having been a location for 1997’s Lost Highway). He hasn’t felt the need to show his art on a grand scale before, so why, I wonder, does he want to exhibit it now? “Well… I didn’t really want to,” is his characteristically perverse response.

Perhaps one of the main reasons is the fact that Lynch is most often described as an artist, not a filmmaker, a title that when used in the context of movie reviews suggests he has moved beyond the mainstream position he found himself in when Twin Peaks (1990–1) afforded him the double-edged honour of cult household name. The forthcoming Cartier show provides an opportunity to assess whether he can be described as an artist in the conventional sense.

When it comes to films, the past decade has seen the director abandon the rudder of accessibility that financiers insist upon; instead he pioneers an experiential type of cinema in which sound and image usurp plot, where character is destabilised, formula negated and conclusive understanding eluded. Inland Empire, his first experiment with digital filmmaking, sees him reach the most extreme point of this trajectory to date.

Lynch’s improvised approach to digital film – including smudging out faces, layering images and using extreme close-up to create texture in the notoriously flat medium – certainly prompts comparisons to the act of painting. Indeed, Lynch’s creative career was initially that of a painter; he felt an impulse towards cinema as a desire to make paintings that moved. His first film, Six Figures Getting Sick (1966), which will be shown alongside other shorts at the Fondation Cartier, was an animation derived from a painting. And even as his career as a filmmaker developed Lynch never abandoned his commitment to painting, while further expanding his output into the domains of photography, sculpture, music projects and furniture design. Never ostensibly made for an audience, these works function as important creative outlets for someone who is a restless doer. However, many pieces, including drawings on Post-it notes and lined paper that incorporate scribbled phone numbers, have never been publicly displayed before. Indeed, the promise of some kind of insight into his creative process – something he is not at pains to overly elaborate upon in interviews – is ultimately what makes the forthcoming Cartier show such a tantalising proposition.

A prominent ‘Lynchian’ trope – the freak, and a fascination with deformity – is suggested with a sad humour in the pathetic melting hunks of snowmen photographed outside suburban homes, or digitally manipulated images of vintage erotica. “There’s an attraction and a repulsion simultaneously,” he explains. “It’s a human thing. It’s a different angle on the human condition. A distortion or a disease or an abnormality always makes something start happening in the brain. It’s really interesting. It makes you look at the human being in a different way. I think it’s like Diane Arbus’s photos of those things, like Francis Bacon or Edward Hopper – they start making you dream.” In Lynch’s formative years, as a young painter in the 1960s, those artistic reference points were, and of course continue to be, iconic.

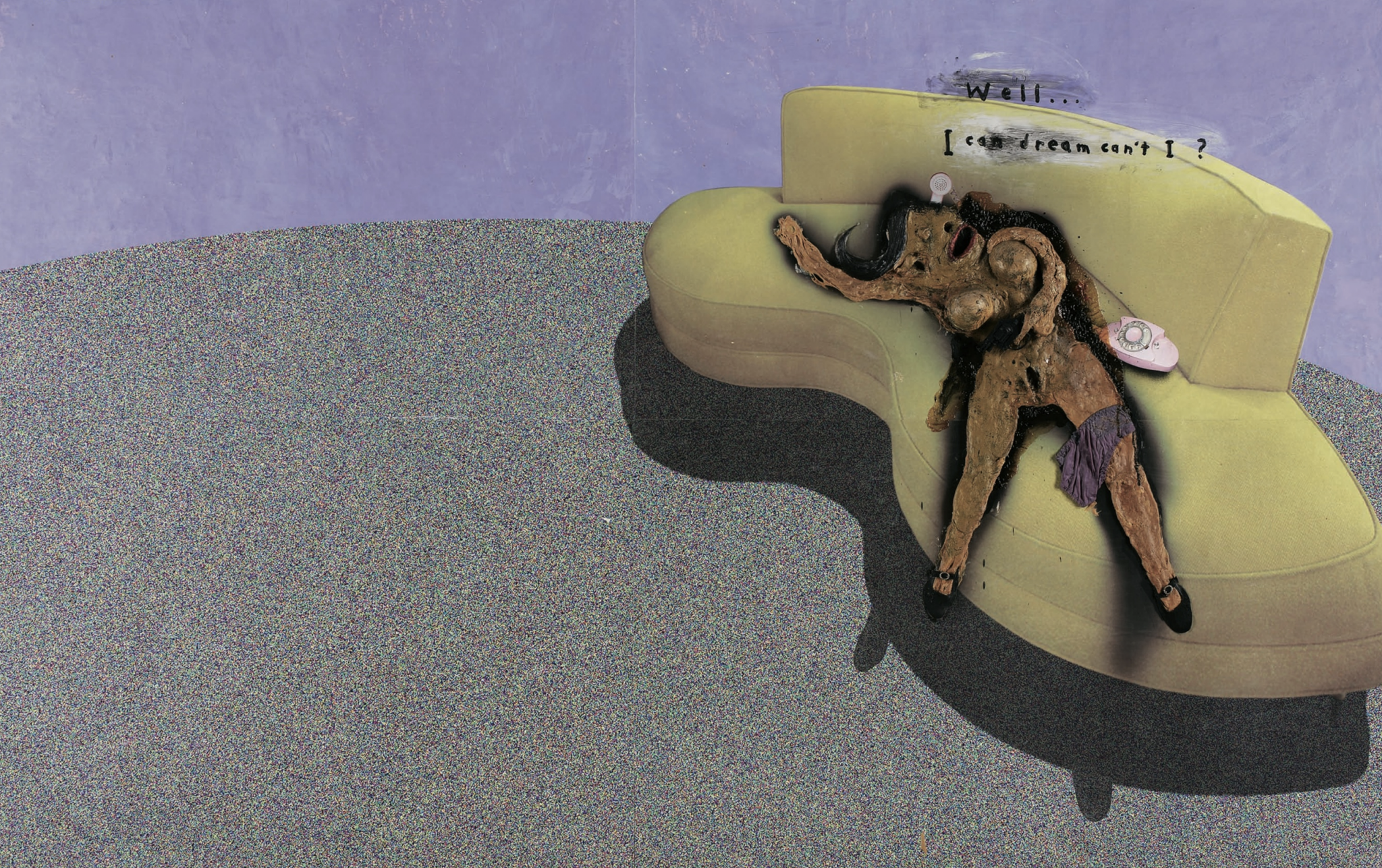

When it comes to Lynch’s filmmaking, the impact of these figures is well documented; when it comes to his art, Bacon’s influence in particular is especially notable in both his earlier and most recent painting. Among the latest output, Well… I Can Dream, Can’t I? (2004) is a giant mixed-media work of a naked woman masturbating on a couch. And it presents its subject’s fleshy shape in mottled corporeal textures familiar from Bacon – though in Lynch’s hands the paint comes across as a veritably volcanic eruption of anxiety. The paint, so thickly impastoed it becomes sculptural, seems to bubble with the distortion of decay, while her vagina, eyes and leering mouth are pitch-black holes. Offsetting this grotesquerie is an expanse of smooth, calm-looking grey and purple paper demarcating a room of unknown proportions, in a composition familiar from Edward Hopper’s wideangle cinematic set-ups.

“That particular painting there is really a homage to Bacon, and it’s three dimensional, with real clothes [the knickers are real], and it’s its own kind of thing. But the space and the fast and the slow area just happened like that,” he says, using speed as an intentionally vague way to describe the painting process (Lynch has often said that he thinks words make things smaller and is thus resistant to lengthy explanations of his method). Getting vaguer still, he continues: “I like this thing of fast and slow. And I like textures; the rest is an abstract sort of thing. It’s partly like a scene with dialogue, but it’s so much more of something that I can’t say in words. So it’s that, it’s just that. It feels correct to me, and I like the way it feels, and it was done.”

The artwork is more than a collection of references. It is, like everything in the exhibition, defined by a unifying vision that is best described as distinctly… Lynchian. This piece works well if considered as an intense distillation of the violence of sexuality, and of the sexuality of violence, his masterful rendering of the uncanny and the bogeymen of the subconscious for which he is renowned on-screen. As such, it’s difficult to look at much of the work without making connections with his movies. The figure described above has a foetal form that recalls the diseased baby from Eraserhead, while the indefinite expanse of the room suggests the uncertain interior geography in which Laura Dern or Naomi Watts lose themselves in Inland Empire and Mulholland Drive (2001) respectively.

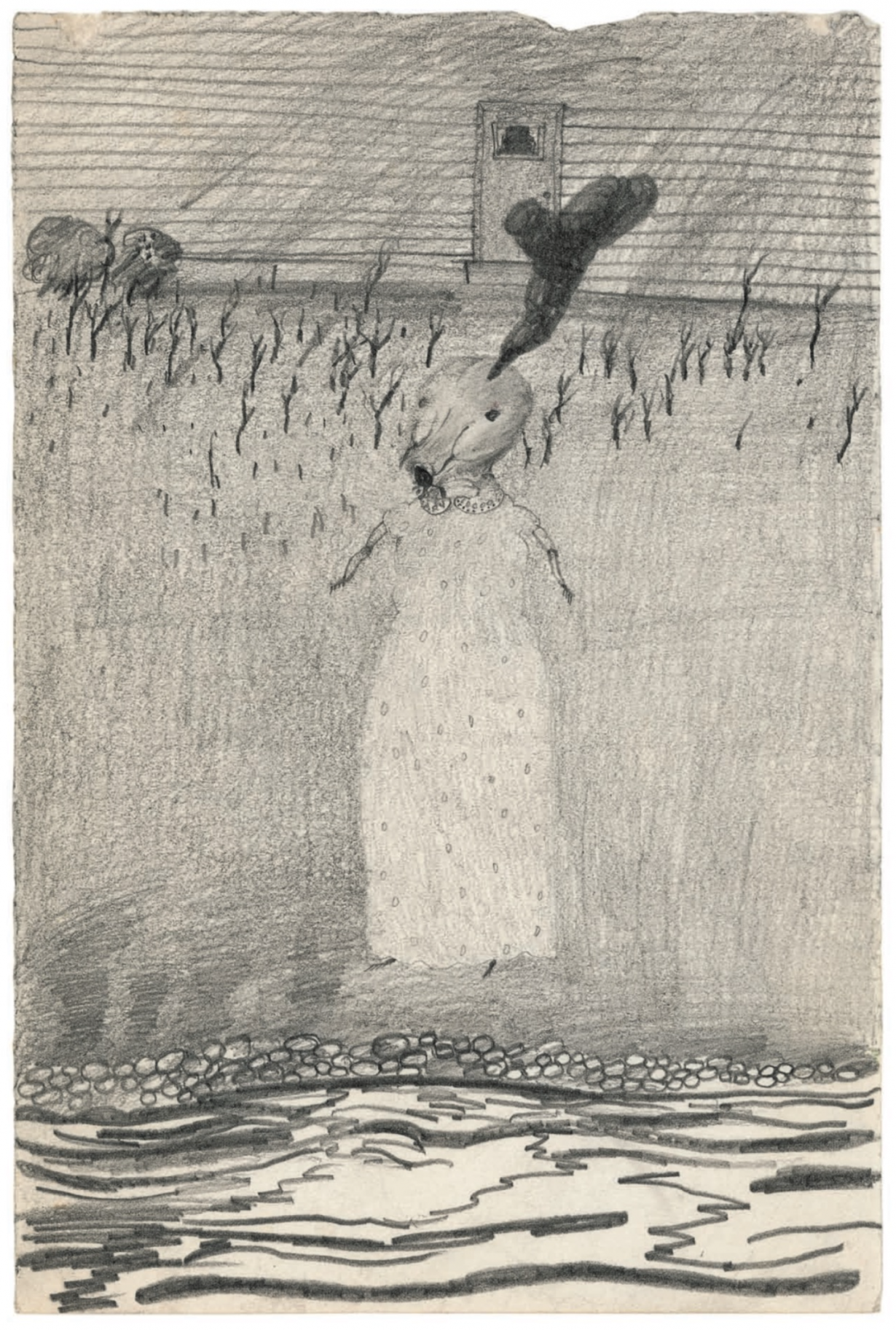

At the same time, the themes of his films, and his method of translating them through character and narrative on-screen, have been explored through many different techniques and devices appropriate to art-making. The confrontational nature of the mixed-media work discussed above could be read as only one example of his handling of the clash between innocence and the big bad world. It is expressed in the faux-naive style of smudgy black and grey watercolours of childhood motifs made sinister, be they dogwalkers or aeroplanes. Paintings dating from the late 1980s to mid-90s explore similar perspectives in an almost entirely black palette with simply delineated stick figures scratched angrily into the paint’s thick surface. Their titles demonstrate his interest in childhood fears that are both all-encompassing and mildly ridiculous, for example Billy Was Halfway Between His House and the Sickening Garden of Letters (1990), Oww God, Mom, the Dog He Bited Me (1988) and That’s Me in Front of My House (1988).

Lynch is resistant to discussing the work’s disturbing aspects. He says his use of live insects, for example, in paintings, feeding on sculpture or pinned regimentally to boards to be photographed, is not a morbid thing, evading the issue with deadpan humour: “No, no, no. A lot of insects arrive when something is decaying, but there’s a lot of insects that are very busy doing things, like bees. I’m not sure if they’re busy 24/7, but they’re very good workers, and they’re making honey.” He also dismisses the Romantic notion of the suffering artist, and he distances himself from any autobiographical reading of the work. “I always say that’s a way for an artist to get chicks to help them and take care of them. It’s real nice to be melancholy and kind of poor, and then the girls come and make warm meals, and it’s so beautiful! But at the same time, if you analyse it, the more the artist is suffering, the less the artist can do. Negativity squeezes the conduit of the flow of creativity.”

Yet Lynch does discuss certain morbid curiosities. When he first lived in Philadelphia, with his friend the production designer Jack Fisk when they were both aspiring artists, he used to make regular visits to the morgue. “Well, because we lived kitty-corner from the morgue, the city morgue, and I feel like it’s important to experience different things, and if you want to experience something very organic and see something that is pretty, you know, powerful, that will make you think in a different way, then visit the morgue, the city morgue, at midnight. It’s really something. And then you’ve had that experience, and it goes into the machine.”

Replete with plans for the kind of atmospheric soundscape that has proved an essential component of his cinema, and curtains that will act as a backdrop to certain works, The Air Is on Fire promises to be the consummate ‘David Lynch’ experience. Yet his own image, specifically as the purveyor of all things weird and freaky, is something he seems less and less comfortable with. His last three films have at times been described as pastiches of his earlier work, as Lynch doing Lynch. As if in answer to this catch-22, Inland Empire is full of knowing winks at his reputation, including a dancing woman shouting “This is so weird!” into camera. “My films are not that weird,” he says, smiling. “But you know, there’s an expression: the world is as you are. Films are as you are. It’s down to the viewer, and everybody has a right to say whatever they want.” His artworks will provide the world with ample opportunities for a fresh perspective on all things Lynchian.

This article was first published in ArtReview March 2007