Defending connoisseurship, criticism and collective intelligence in the age of AI slop

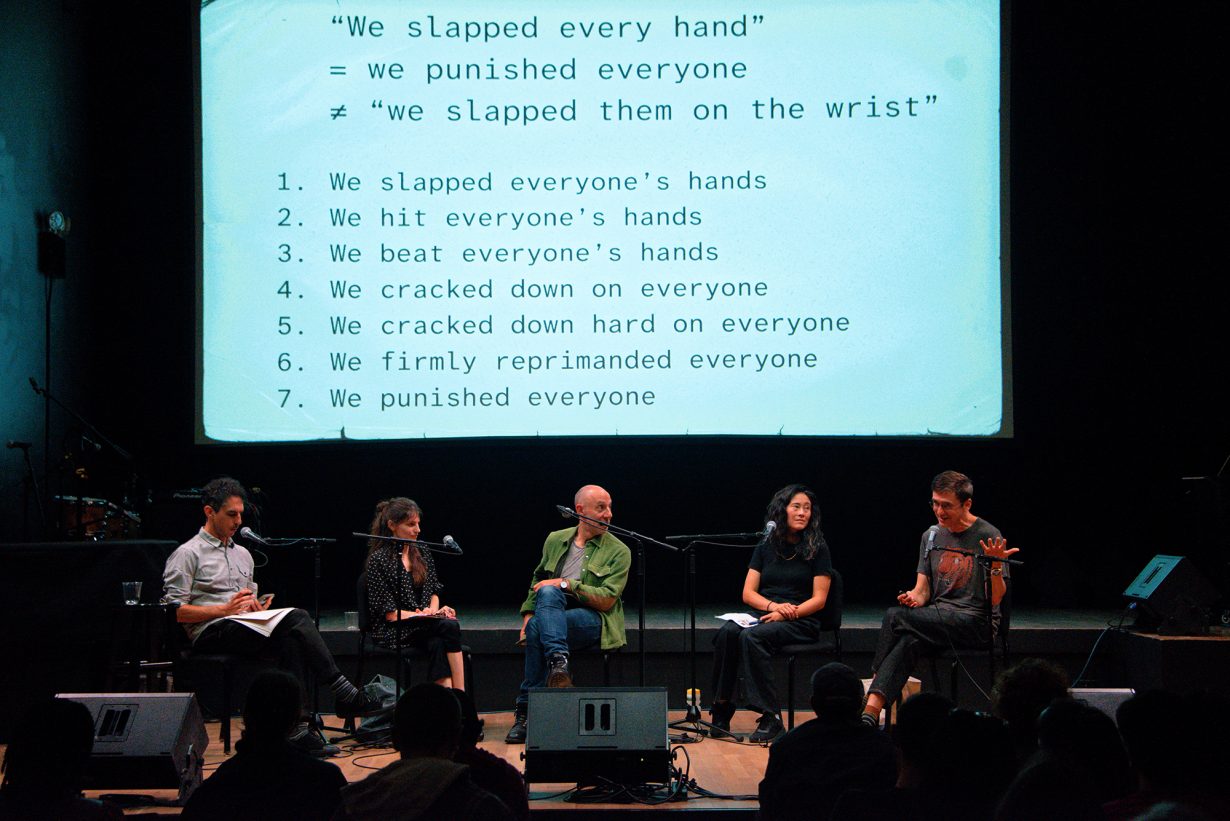

In mid-October, sociologist Alix Rule and artist David Levine, who wrote the widely circulated essay ‘International Art English’ for Triple Canopy in 2012, appeared on a panel titled ‘Language Against Intelligence’ during a symposium organised by the magazine at the Brooklyn performing arts venue Roulette. In their essay, Rule and Levine describe loading 13 years’ worth of e-flux press releases into Sketch Engine and amusing themselves with the linguistic tics that the text analysis software detected. Through the habitual overuse of adverbial phrases, dependent clauses and words like ‘aporia’, ‘radically’ and ‘space’, twenty-first-century art writers unwittingly begot an alien language the authors term International Art English or IAE. In the aughts, IAE rose alongside the expansion of the biennial circuit and the explosion of Web 2.0 to become the lingua franca of the global artworld. Writers versed in its conventions and a bit of continental philosophy could ostensibly churn out meaningless affectations that emptied artworld discourse of its once enviable intelligence.

This concept courted its fair share of controversy. In 2013 e-flux published responses to ‘International Art English’ by artists Martha Rosler and Hito Steyerl. Both respondents took issue with the methodology and spirit of the essay, with Rosler arguing that the use of statistical analysis accomplishes little more than to ‘give the analyst a jump on the messy contingency of reading’ and Steyerl pointing out the absurdity of scraping press releases ‘written by overworked and underpaid assistants and interns’ when ‘authoritative high-end art writing is respectfully left to keep pontificating behind MIT Press paywalls’.

Even though, as Levine noted onstage at the symposium, e-flux’s influence waned over the past decade, the internet became atomised and artspeak, as a result, lost some of its hegemony – and even though the artworld’s “source of authority”, Rule added, referencing art critic Ben Davis’s recent e-flux article ‘Artspeak After Social Media’, is now no longer ‘intellectual references’, as Davis writes, but “social media clout”, as she put it – Rule and Levine’s attitude towards the conventions of twenty-first-century art writing seemed not to have changed, as evidenced when they pulled up a recent e-flux press release (for P. Staff’s show at Bonner Kunstverein) and chuckled at its use of IAE – or what they now suspected was AI-IAE.

Indeed, the panel had been assembled because, as Levine observed, AI was contributing to a revival of interest in IAE. One can picture a continuum that runs from sloppy art writing to AI slop or perhaps even an alliance between these two categories of cultural output against intelligence as it is conventionally perceived. Being able to detect inanity in the former and colourlessness in the latter certainly makes the detective feel more intelligent, more human.

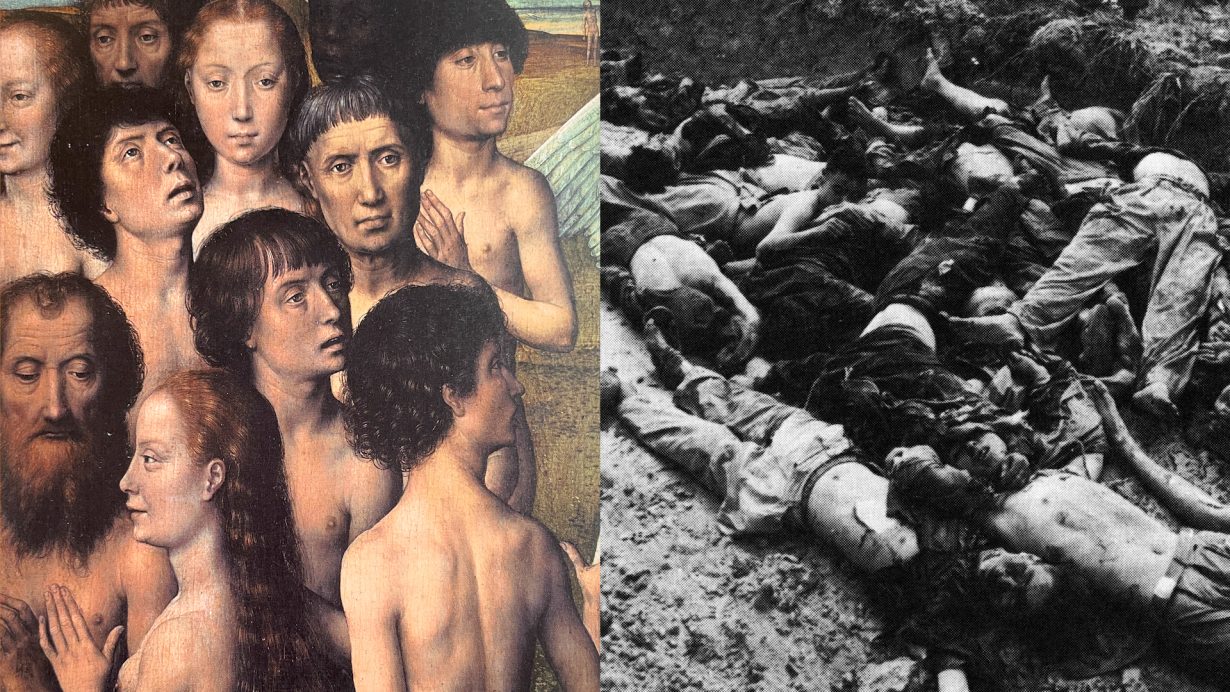

In an older essay titled ‘Connoisseurship and Critique’, Davis reminds us that having a sceptical, ‘educated’ eye was a mark of a connoisseur, such as the nineteenth-century art critic and Italian nationalist Giovanni Morelli, who used stylistic analysis to authenticate Old Master paintings. A ‘great master’, according to Morelli, would render details like figures’ ears or fingers the same way across his works; therefore, someone whose eye has been ‘educated’ cannot help but discern between mere copies and counterfeits and real masterpieces. During the mid-2010s, when Davis was writing this essay, however, connoisseurs had ventured beyond the artworld and were setting their sights on Nike sneakers and Hollywood movies. It had become fashionable to apply critical analysis to pop culture artefacts that were meant to be ephemeral, consumed, rather than rarified works of fine art, just as it was apparently compelling to scrutinise throwaway press releases over, say, scholarly monographs. But the quest to point out IAE or AI-IAE – or discern between the two – is in a sense the inverse of Morellian connoisseurship. Instead of studying a canvas for uniquely stylised earlobes and fingernails, the sceptic in the age of artspeak and AI slop elects to participate in a perpetual search for deficiency.

One of Rule and Levine’s fellow panellists, the literary historian Dennis Yi Tenen, attempted to push the conversation past cynicism by acknowledging the aggregated labour behind any and all acts of intelligence. Tenen’s advice was this: it isn’t productive to think about intelligence as an individual attribute, one that an art writer or a machine may or may not possess; what’s more useful is studying how writers and ai systems marshal the resources of collective intelligence. Intelligence – even the kind exercised by Morellian connoisseurs – is and has always been social, tool-based and spatially and temporally distributed.

Echoes of Tenen’s ideas emerged a week later at a forum titled ‘Matter of Intelligence’ organised by the Vera List Center, at New York’s New School. The keynote lecture by philosopher Matteo Pasquinelli, ‘AI and Madness: On the Disalienation of the General Intellect’, examined the mechanisation of intelligence via psychometrics, a subject Pasquinelli explored in his book The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence (2023) to show that AI does not model the human brain so much as it models stratified labour and social relations. Intelligence, as Pasquinelli conceives of it in his book, signifies the measurement, disciplining and surveillance of labour. It comprises, as he stated in his lecture, “the institution of public education” and “the spontaneous know-how of the working class”. According to this view, one would gain less from criticising AI-IAE than from observing how the intelligence of a system like the artworld – with its complex social division of labour – produces forms of knowledge that alienate even its insiders.

How, in this sense, might ‘language against intelligence’ sound? Perhaps like parody, à la (question–repeat–failure–record) (2025), a lecture-performance by artists Sandra Erbacher and Ruth Estévez that took place at the Vera List Center Forum the morning after Pasquinelli’s keynote. Here, the performers took up the subject of intelligence by conducting research on women such as Carrie Buck and Britney Spears who’d had their rights stripped on account of their perceived aptitude. Throughout the performance, Erbacher and Estévez volleyed invasive questions excerpted from archival documents, trial transcripts, press clippings and IQ tests across a table: “Are your parents living?” “Could you still live with them?” “Can you feed yourself or do you prefer to be fed by others?” Their mutual interrogation was intermittently paused when old-timey instruction videos for visualising the ‘perfect human’ and implementing mnemonic techniques were projected on screens in the lecture hall and rapidly devolved into pointed absurdities: “How many buttons do you have on your jacket?” “Do we want to perform a test that everybody can pass?” “How should a normal person be compared to another normal person?”

Parody, as Susan Sontag wrote in ‘Against Interpretation’ (1964), is a genre capable of eluding critics, whose inclinations to foist Marxist, Freudian and religious readings onto self-sufficient artworks constitute what she called, some 60 years ago, ‘the revenge of the intellect upon art’. Equally resistant is the work ‘whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct’ – the work that is, in short, so ‘good’ that it ‘frees us from the itch to interpret’. Suppose art writers today took similar approaches to outfox the maddening social and linguistic systems that dictate our labour. Suppose we actively deconstructed the language of our texts at every turn, or we tried to be brilliant. Barring that, we could try to ‘recover our senses’, as Sontag suggests at the end of her essay, so as to better attend to the art around us. For her, ‘senses’ meant our ability to see, hear and feel. For us, it might also mean our sanity.

Read next This ‘new’ era of Abstract Expressionism is the perfect fit for an age of hyper-individualism and AI-powered press releases