The rejection of Defne Ayas as curator of the 2024 biennial in favour of Iwona Blazwick reveals the increasing limitations of artistic freedom in Turkey

On 3 August, the Istanbul Culture and Arts Foundation (IKSV) announced Iwona Blazwick, the former director of the Whitechapel Gallery in London, as the curator of next year’s Istanbul Biennial, scheduled to run from 14 September to 17 November 2024. ‘We are delighted that Iwona Blazwick has accepted our invitation to curate the 18th Istanbul Biennial. Her depth of experience and her long association with the Biennial make her an ideal choice to lead the team for 2024’, the foundation stated in an announcement. Blazwick’s curatorial framework and artist list for the biennial are as yet unannounced. More curiously, however, the IKSV also chose not to reveal the names of the Istanbul Biennial advisory board members for this edition – the first time in a decade that these have not been made public.

Since the Istanbul Biennial’s inception in 1987, the principles of democracy, plurality, hybridity and cultural dialogue have been highlighted and championed by its curators, and it has seen millions of visitors over the years. The members of the advisory board remained largely unknown until 2010 when IKSV began publishing their names. That year, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Ayşe Erkmen, Melih Fereli, Hou Hanru, and Jack Persekian picked Adriano Pedrosa & Jens Hoffman’s project for the twelfth edition of the biennial. When it was announced in 2020 that Ute Meta Bauer, Amar Kanwar, and David Teh would curate the last edition of the Biennial, the names of the advisory board who appointed them were made public: Iwona Blazwick, Ayşe Erek, Yuko Hasegawa, Agustín Pérez Rubio, and Levent Çalıkoğlu. By contrast, the opacity of this year’s selection process has led to the formation of an initiative comprising a group of artists, researchers and art professionals who demand transparency. I was invited to join and became a silent observer as the initiative contacted members of the Biennial’s advisory board and the curators who pitched proposals for the next edition to piece together what seemed a baffling puzzle.

Blazwick herself, the group found, was part of the advisory board that was tasked with selecting a curator for the 2024 edition. As a private foundation, there is of course nothing in the IKSV’s mandate that requires it to commission a project recommended by the advisory board. There is also nothing to stop the foundation from choosing a board member as one of their curators; while they have done so in the past, this was only after those members had already left the board (including Christov-Bakargiev and Ute Meta Bauer). What makes Blazwick’s case unique is that she was a member of the very board that was dismissed before the foundation appointed her. Speaking on behalf of the transparency initiative, video artist Köken Ergun and curator Merve Elveren told me the members of the initiative are still waiting to learn from IKSV if there is a grace period or moratorium – standard practices to avoid ethical questions regarding the selection process – on former board members applying as curators for the biennial. “It is crucial to emphasise that while the IKSV is a private foundation, it has a public mandate and hence public responsibility”, they added. “It uses private and public funding for its exhibitions, programs, initiatives and research. It also has a longstanding research program in cultural policy with clear public stakes. We ask these questions because we all want IKSV and the Istanbul Biennial to be more public, trusted, inclusive and transparent.”

The advisory board for the selection process of the 18th Istanbul Biennial comprised curators Agustin Pérez Rubio and Yuko Hasegawa; art historian and curator Selen Ansen; Turkish-Armenian artist Sarkis; and Blazwick. In December 2022, five curators were invited to send their proposals for the 2024 edition. The board unanimously recommended the proposal of Defne Ayas in late January 2023 and informed the IKSV Biennial Administration of their decision. Much to their dismay, however, the administration team notified the board that they would not be able to proceed with their curator of choice; the administration also refused to commission the other proposals. Agustin Pérez Rubio resigned from his role on the board in protest, arguing that the process lacked transparency. Soon afterwards, Selen Ansen and the artist Sarkis also resigned from the board, sharing Rubio’s concerns; in response to my email, Ansen confirmed her resignation. “I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to comment on this, except that I resigned from the IKSV Advisory Board after IKSV appointed Iwona Blazwick as the curator of the 2024 Biennial”, she said. “I sent my resignation to the IKSV administration, and other Advisory Board members in an email which features my reasons for doing so.” Over the following days, a solution was found by dissolving the advisory board for the 2024 Biennial. Instead, the IKSV Administration appointed Blazwick as the next curator instead of Ayas. In their correspondence with me, the IKSV did not dispute this chronology of events.

The general director of IKSV Görgün Taner told me that it was not the advisory board but the IKSV themselves who selected Blazwick. “The decision to appoint Ms. Blazwick was taken by IKSV further to the non-acceptance of the advice of the Advisory Board by IKSV. It is to be noted that the Advisory Board gives advice which is not however binding and IKSV may act independently of such advice.” He added: “Ms. Blazwick’s work is highly respected by IKSV as she is an internationally renowned curator with wide knowledge of contemporary art and deep knowledge of the context in Turkey thanks to her experience in the Advisory Board from which she stepped down. IKSV at this time deemed that it is a moment in which to nominate an international curator to lead the next edition artistically.” Following the dismissal of a board that she was herself part of, Blazwick chose not to support Ayas but instead to accept her own nomination as curator. This seems a troubling and professionally unethical decision.

Seven months have now passed since the controversial board meetings, and the issue has resurfaced following IKSV’s announcement last week. Curator Duygu Demir demanded answers: ‘Iwona Blazwick, the curator of the upcoming Istanbul Biennial, has consecutively served on the biennial’s advisory board in 2015, 2017, 2019, and 2022. We are wondering: Who are the members of the advisory board this year? Why have these names not been publicly shared yet? Is Blazwick still part of the board? Has she selected herself?!? If so, did she submit a proposal like others in accordance with the invitational format, before being selected?’ On 6 August, the Turkish arts website Sanatatak joined in. Soon, Turkish social media was ablaze.

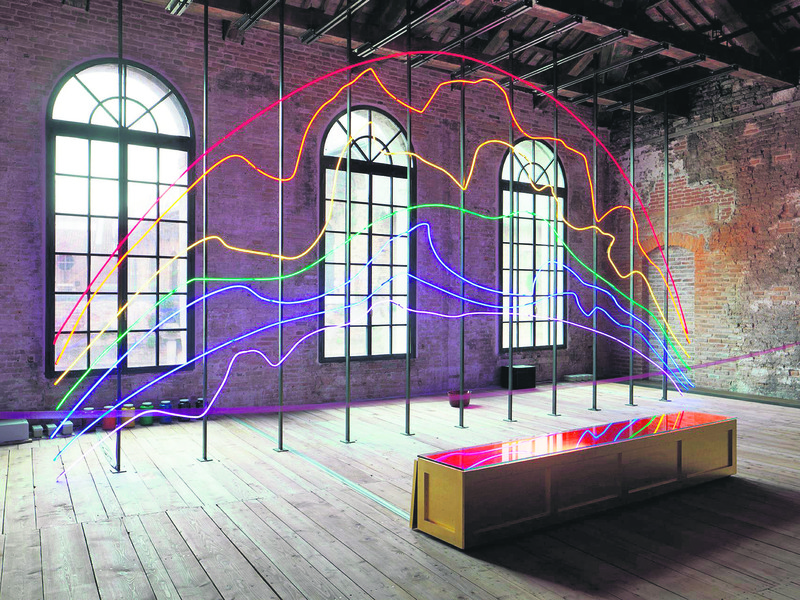

Defne Ayas stated to me her hope that these developments pave the way for a more transparent selection process and a dialogue-based art ecology in the city; she has chosen to donate her proposal-phase fee from IKSV to charities supporting recovery in Turkey’s earthquake zone. Ayas is currently working on an upcoming exhibition with Sarkis at Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, which will open on 27 October. One can only speculate that her prospective collaboration with IKSV in 2024 may have caused unease in some circles due to pre-election political sensitivities in Turkey. Such tensions may also have taken root in 2015, the year of Ayas’s previous partnership with the foundation. In 2014, the IKSV selected Sarkis for the Turkey Pavilion at the 72nd Venice Biennial; Sarkis picked Defne Ayas to work with him as curator. The resultant installation, Respiro, celebrated the legacy of the slain Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink. An accompanying exhibition catalogue featured essays by Ayas, David Kazanjian and Wendy Meryem Kural Shaw, as well as a text by Dink’s widow, Rakel, who referred to the Armenian genocide to describe the pain suffered by her people. IKSV organizes the Turkey Pavilion for the art and architecture editions of the Venice Biennale, with the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. In 2015, the Turkish Ministry of Culture reacted to the booklet’s publication by blocking its distribution due to political sensitivities. Cumhuriyet newspaper reported the controversy, but there was little further coverage of the issue in Turkey.

It does not bode well for Turkey’s art scene that resignations from the advisory board happened seven months ago in January but were never publicised. If IKSV were to eventually veto without explanation Ayas’s proposal, which was unanimously chosen, then why did they invite her to submit a proposal in the first place? If they won’t listen to the advisory board, why do they have one at all? It also raises institutional questions. Ergun and Elveren, from the transparency initiative, believe that “a credible and inclusive institutional practice regarding the selection of the curators requires that IKSV continues to announce the advisory board members, be transparent about the selection process, and remain open and responsive to criticism and respond to enquiries for transparency and accountability. We hope that this dialogue will continue in the coming years”. In Turkey, demands for institutional transparency are rooted in fears about a pervasive political silence that may soon take the country hostage, particularly as government pressure on the fields of arts and culture continues to grow. These demands and concerns are fundamental in public life; the artworld must commit to adopting them if artistic freedom of expression is to be protected for the future.

Kaya Genç is a journalist and novelist from Istanbul. His most recent book is The Lion and the Nightingale: A Journey Through Modern Turkey, 2019