In the 2003 Warner Bros film Looney Tunes: Back in Action there’s a chase sequence that, for various convoluted reasons, ends up in the Louvre. Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny are being pursued by their longtime nemesis, the shotgun-wielding Elmer Fudd, and they decide that their best course of action is to hide inside the paintings of the museum’s fictionalised collection. First they jump into Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), Fudd following, his gun going as limp as the painting’s floppy clocks. They jump out and into The Scream (1893–1910), the clean lines of the three characters becoming as wavy as Edvard Munch’s brushstrokes. It ends when Bugs and Daffy lure Fudd into Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884–6) and, with an electric handheld fan, blow apart the pointillist dots of paint that make up the hunter’s form.

Back in the real world, the population of Toontown (which Robert Zemeckis’s 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit locates as being near Hollywood) hasn’t quite made it to the Louvre yet, but they seem to be getting everywhere else in art. Let’s take a quick, no doubt incomplete, stock-check of recent artists who have incorporated motifs from the pantheon of Western toons in their work. All to a greater and lesser extent owe a debt to post-1969 Philip Guston, and his dark corralling of American pop culture: bloodshot, nihilistic and hungover, post-Woodstock (where Guston had moved in 1967 and lived until his death in 1980).

There’s Ian Cheng with Bugs and Fudd in his shootergame-style animated video for the Liars’s dark, pounding 2012 single Brats, Dan Colen (the Kool-Aid Man, Roger Rabbit and Wile E. Coyote), Ed Fornieles (Stewie Griffn), Anthea Hamilton (various characters from The Simpsons, 1989–), Paul Housley (Snoopy and Woodstock), Sam Keogh (the Smurfs), Mark Leckey (Felix the Cat), Oliver Laric (Disney’s Mowgli and Christopher Robin), George Henry Longly (Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble), Bjarne Melgaard (the Pink Panther), Joyce Pensato (predominantly Felix again, but also Mickey Mouse and Homer Simpson), Zach Reini (Mickey Mouse) and Jordan Wolfson (Bart Simpson and Charlie Brown). This is without considering the artists who do not utilise specific characters but have invoked the aesthetics of traditional animation (Peter Wächtler and Mathias Poledna) or who borrow the tropes of grotesque caricature and anthropomorphisation from the toons (George Condo and Armen Eloyan).

5 images

Of the artists listed above – space prevents me from going into the detail of each – we can perhaps separate them into two camps. The first are those who use toon imagery in a Warholian sense, invoking the motifs as one of many on the capitalist brandscape. Longly’s performance at the Serpentine Gallery in 2013 took the form of a fashion show, and involved an altered line-drawing of Fred and Barney smoking, taken from a 1950s advert for Winston cigarettes, appended to the clothes. (Longly isn’t the only one to notice that toons can be fashion: in June last year Jeffrey Katzenberg, CEO of DreamWorks Animation, told the Licensing Expo in Las Vegas that Felix the Cat was ‘a true icon [and] we plan to make him one of the most desired fashion brands in the world’.)

Likewise Fornieles’s mixing of the Family Guy (1999–) baby with any number of other Generation-Y tropes in his 2013 installation Despicable Me 2 at Mihai Nicodim, Los Angeles, updates a dubious lineage that counts Jeff Koons’s Banality series (1988, in which Koons co-opted cultural motifs from his generation including the Pink Panther and Michael Jackson) as a predecessor. In Fornieles’s work, in a manner akin to navigation in the online world, Stewie joins myriad images loosely connected by tenuous association. The majority of artists discussed here, however, to varying degrees engage in questions pertaining to an ontology of the cartoon character, pulling the image out of the pictorial fiction and into the ‘real’ world. The toon is an image imbued with a nostalgia for the cultural history of cinema and television but also narratives that operate in the hermetic world of Toontown itself. So an image of Bugs can be read within the context of cultural or personal histories (he first appeared in 1940; I remember watching reruns on television during the 1980s but always preferred Yogi Bear), yet it can also be read within the mythology of their world (Bugs has a love–hate relationship with Daffy, and they both hate Fudd).

The double-life status of the toon is perhaps most simply described, perhaps unintentionally, in Mark Leckey’s narration of his video Prop4aShw (2010/13). As 3D renderings of landscapes give way to a lecture by the artist watched over a webcam by a man dressed as Felix the Cat, Leckey monotones, “This is a proposal for a show that will be populated by things that have one foot in this world and one in another. And it’s going to toggle between the two.” And while Roy Lichtenstein’s Look Mickey (1961), his near-faithful reproduction of a Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck cartoon strip, was basically formalist commentary (produced as Lichtenstein had grown weary of the spiritual grandstanding of Abstract Expressionism), and from our contemporary list of artists, Housley’s repeated use of the Snoopy and Woodstock motifs are receptacles for the artist’s process-based experiments in the possibilities of paint; many of the artists working with toons seem to be engaging in the opposing struggle to pull the characters out of their own pictorial world and into our own.

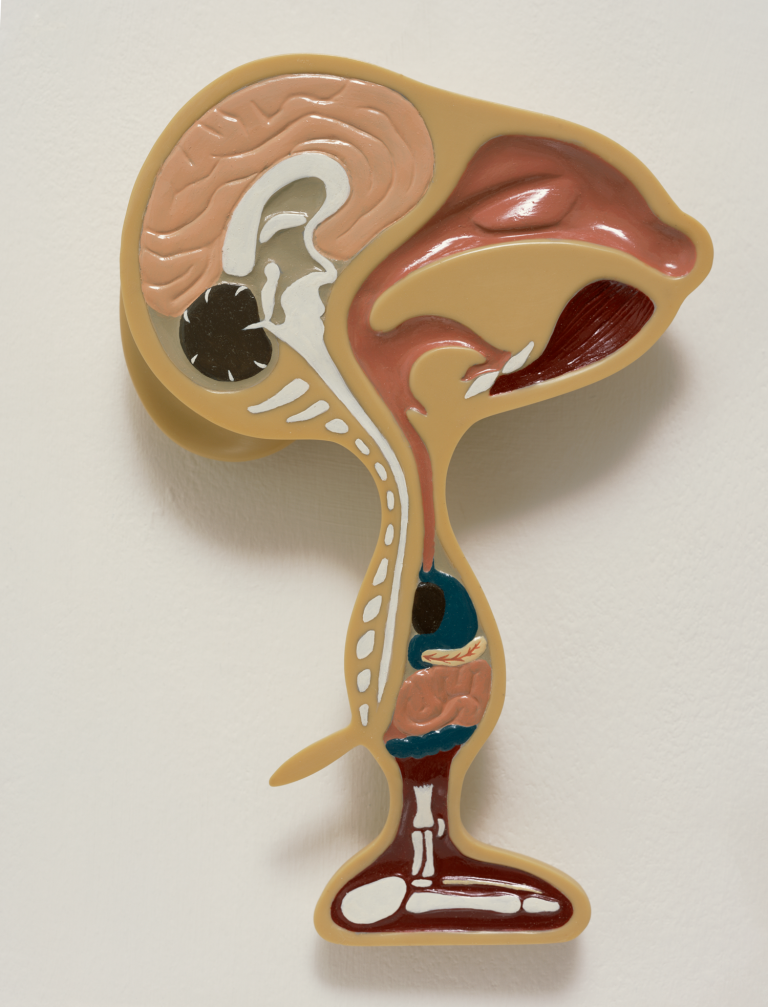

The show that Leckey describes in Prop4aShw, the touring The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things, would include David Musgrave’s Animal (1997), a bisected 3D model of Snoopy that shows the bipedal dog’s internal organs. Musgrave, characteristic of contemporary artistic users of cartoon motifs, seems to be indulging in a real-world materialisation to complement the Toontown anthropomorphisation (though toons are quite often distant relatives, aesthetically, to the animals they’re supposed to represent – Bugs doesn’t look much like a bunny – hence my use of ‘toon’ as a catchall moniker). So while it is one thing when, in a Peanuts (1950–2000) strip, Snoopy’s toon-human owner Sally has to write about animals as part of her homework and asks for Snoopy’s help, and Snoopy thinks to himself, ‘How can I help? I don’t know any animals’, Musgrave giving Snoopy an oesophagus, a stomach and a colon – pulling him from the flat place of the cartoon into the ‘living’, ‘breathing’ material world – is another. Leckey has said of Musgrave’s sculpture, ‘I like this idea of a cartoon having real viscera, these kind of internal organs as if it’s a live thing ’cause we believe Snoopy is alive – well I do anyway.’

If Musgrave has permitted one toon a digestive system, then Bjarne Melgaard has given another all kinds of other physiological urges. The Danish artist keeps returning to the figure of the Pink Panther; but in Melgaard’s vision, Friz Freleng’s suave and sophisticated catification of 1960s style has fallen on disastrous times. In his 2013 exhibition Ignorant Transparencies at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York, Melgaard produced multiple versions of the toon in fibreglass. These three-dimensional Pink Panthers were characterised, however, by their bloodshot eyes, trampy appearance and, in the largest version, toking on what could well have been a crack pipe.

Which is all quite socially acceptable when compared to Melgaard’s work for the Lyon Biennale the same year. Here the Pink Panther towers over a realist sculpture of a human woman and, wearing a top hat, fucks her from behind with a grossly outsized sequinned penis. Besides the obvious shock Melgaard is engineering by debasing an icon of childhood nostalgia in such a way, the artist is also playing the game of toon materialisation. To see this lecherous Pink Panther, the viewer had to wade through piles of old clothes on the floor. It was actually quite diffcult terrain, instilling an awareness of one’s own physicality, making the shock of the Lothario pussy even harder to stomach.

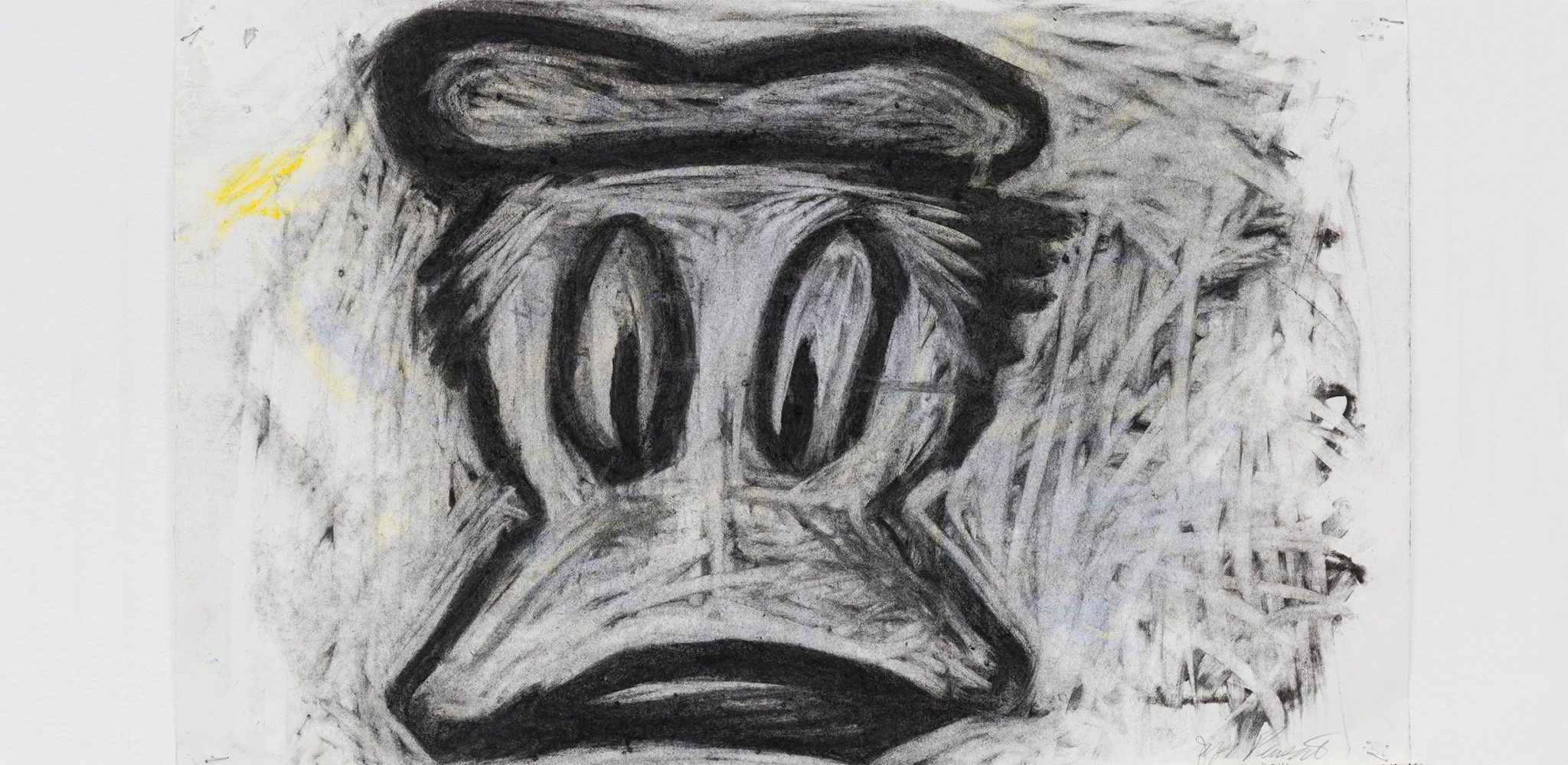

There was similar immersive busyness to Joyceland, Joyce Pensato’s 2014 exhibition at London’s Lisson Gallery. Alongside a series of paintings – characteristically smeared, drippy, enamel portraits of cartoon characters ranging from Donald Duck and Felix the Cat to Homer and Lisa Simpson and South Park’s (1997–) Eric Cartman – Pensato showed Joyceland in London 1981–2014 (2014), an installation of toys and other cartoon ephemera the artist has accumulated in her Brooklyn studio. Mickey Mouse costume heads sit among Cookie Monsters and armies of Elmos; Kenny and Cartman hobnob with Donald Duck. Yet despite the fact that some of this merchandise is animatronic, there was something strangely lifeless about all these toys when compared to Pensato’s actual paintings. Similar to Anthea Hamilton’s use of latex Simpsons masks (for example in Moe / Chess (Upper + Lower), 2009, in which the rubbery, seemingly decapitated head of the Springfield bartender is encased in a glass vitrine), in Pensato’s paintings the toons are simultaneously familiar and monstrous. Staring straight out of the canvas, the view close-cropped to their faces only, they take on the guise of antiheroes, capturing the mania and violence of Toontown more than any of the marketing ephemera in the artist’s installation work ever does.

Theodor Adorno argued that cartoons taught capitalist conformity, writing in 1969 that ‘Donald Duck in the cartoons and the unfortunate in real life get their thrashing so that the audience can learn to take their own beating’. Yet I think it is Who Framed Roger Rabbit’s Judge Doom who is more on the money in his description of Toontown. Christopher Lloyd’s character (who, it turns out, wants to demolish the city to build a freeway lined with malls and fastfood joints) says in the film, “My goal as Judge of Toontown has been to rein in the insanity. To bring a semblance of law and order to a place where no civilised person has ever been able to set foot.” It is this sense of anarchy – the lack of control that often breaks into violence; the ‘fear’ that, as Walter Benjamin wrote in 1931, characterises the world of Mickey Mouse – that seems to attract artists to toons.

Dan Colen, again at the 2013 Lyon Biennale, made a series of realist sculptures including Roger Rabbit and the Kool-Aid Man, showing them crashing through the internal gallery walls, their progress marked by appropriately shaped holes. Similarly the young Denver-based artist Zach Reini has made a number of latex-on-canvas works titled WWMMD? (2011– 14, presumably an acronym for ‘what would Mickey Mouse do?’) in which the Disney icon has fled the frame, leaving just a silhouette void in his wake. The toons – the massive, freewheeling, instantly recognisable icons that they are – are there to muck up the status quo. In the end, perhaps the two camps of artists using the motifs aren’t so different, and the reason that so many toons have made it into contemporary art of late is that they are recognised as ciphers for the contemporary role of the artist itself, toggling between the two worlds of anarchy and consumption.

This article was first published in the January & February 2015 issue of ArtReview