A superhero who said he would live forever, Adrian Street’s greatest artwork was himself. Turner prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller looks back at the life and times of a cultural icon – as told to Louise Benson

The first time I saw Adrian Street was in a photograph of him and his coalminer father, taken by Dennis Hutchinson for the Sunday People newspaper in 1973, which has often been reproduced. It appears in The Wrestling (1996) by Simon Garfield, a firsthand account of the wrestling scene in the UK, and was used as the album cover for England Made Me (1998) by the band Black Box Recorder.

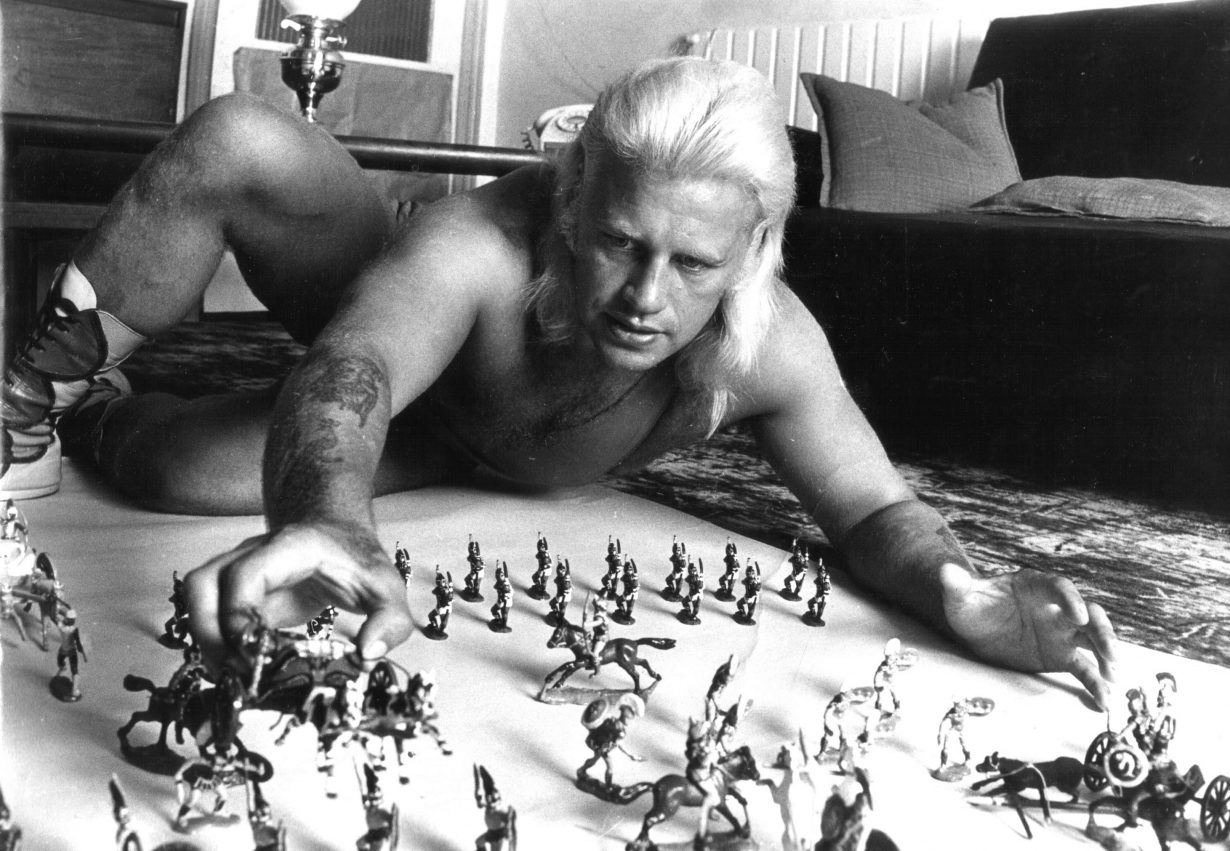

Instantly curious, I contacted Adrian in Florida in 2010 and he responded immediately; within a couple of months, I was out there filming him. He lived on a little piece of land and a house that he was very proud of in Pensacola, Florida, in a very extreme climate. He made a lot of the furniture and the artwork in the house himself, and he had a gym and a room that was just filled with mirrors he would pose before. It was an entire world of his creation, filled with mementos, images and videos of him wrestling – a museum to himself and his achievements.

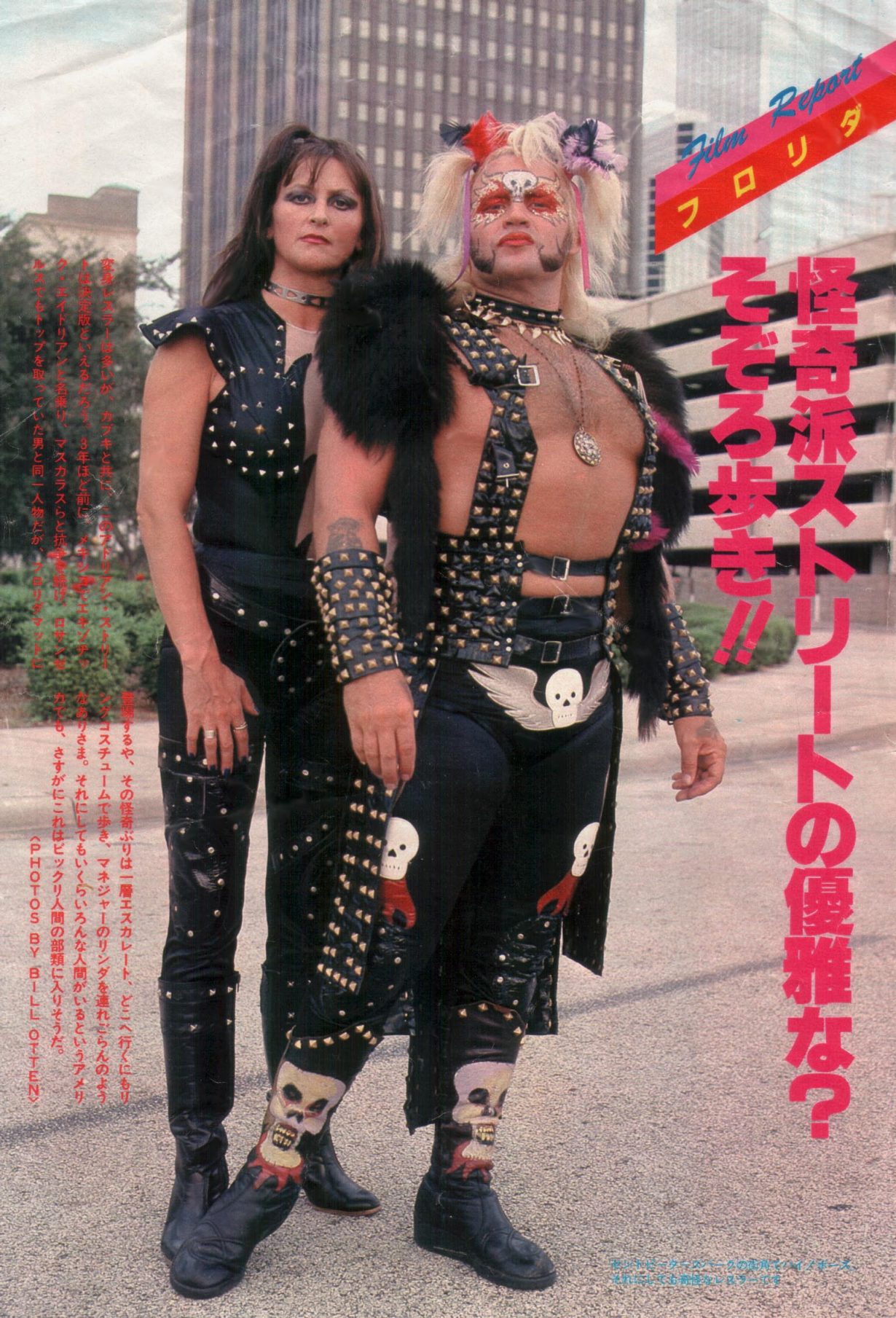

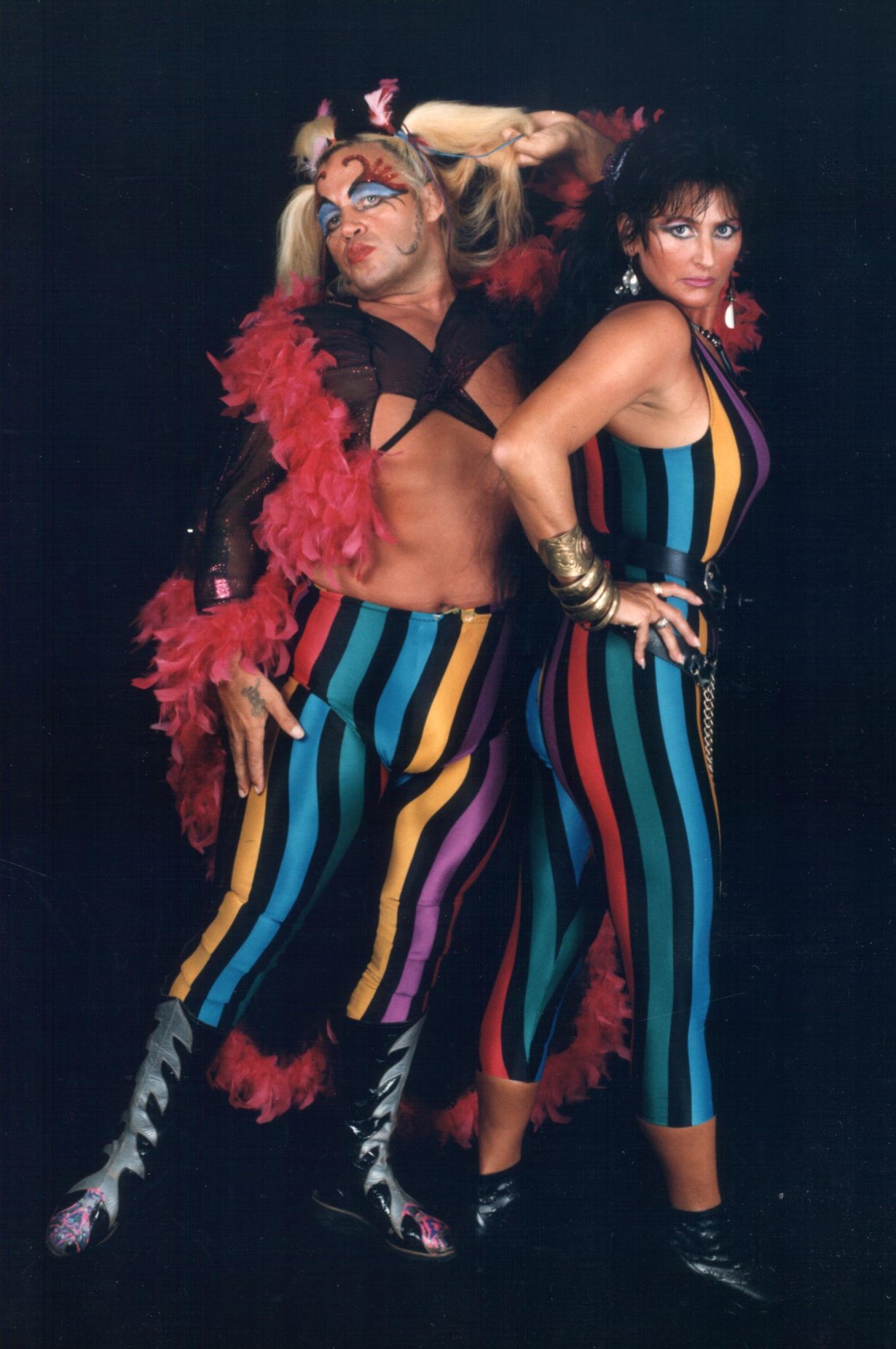

An émigré to the United States, Adrian made the decision to leave Britain in the 1980s because wrestling was declining in popularity and increasingly absent from television scheduling. In America, he reinvented himself as the ‘exotic’ Adrian Street. He played an outrageous character who was both very masculine and very feminine, with his long bleached hair often worn in pigtails, glittery make-up and spandex costumes. His act played upon people’s homophobia, as he would say, and he loved pushing boundaries.

From his childhood right through his career, he always craved attention. Adrian’s father, who fought in the Second World War, was absent when he was a young child and virtually ignored him throughout his life. Adrian desperately wanted his approval but he never got it, and so instead sought the approval of everybody else. This is what makes that photograph of the two of them so powerful. He’s showing his father what he’s made of himself – and how different he is.

Americans were particularly intrigued by the specificity of his humour, the wordplay and the campiness of it. He learned all that when he first came to London as a teenager in the 1960s, when he worked as a builder while training to be a bodybuilder. He spent time in clubs and was often around gay men, where he would have picked up certain phrases and ways of behaving. He knew the writer Daniel Farson and artist Francis Bacon from various drinking dens, but he knew the criminal underworld too. He mixed with a very unusual group of people, and the act that he adopted later was influenced by that time spent in Soho.

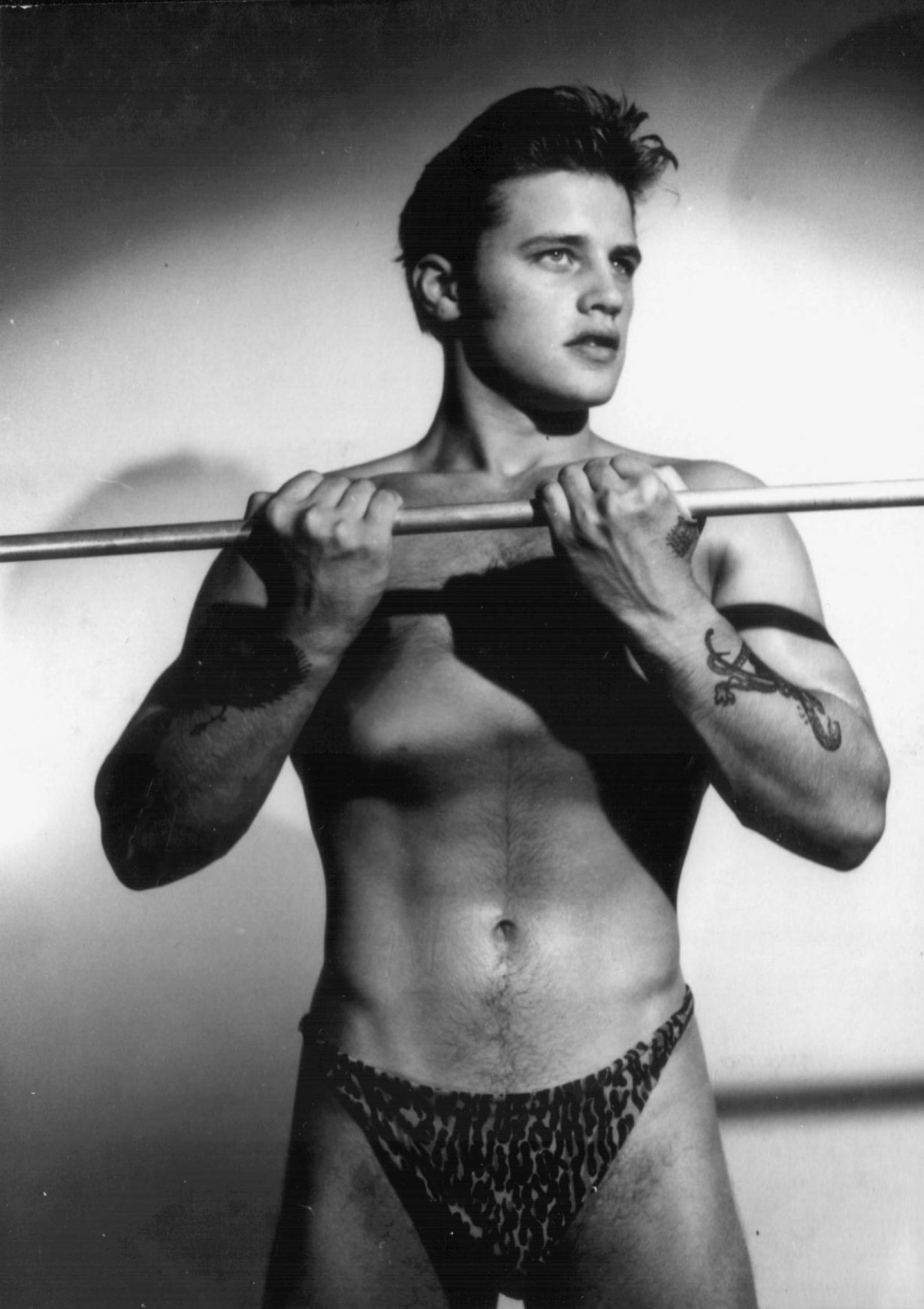

Adrian understood the homoeroticism of wrestling in a way that many others in the industry didn’t. Bacon was another, using images of wrestlers as source material for Two Figures (1953) and Two Figures in the Grass (1954), which show men locked in an embrace resembling both intercourse and combat. You could say both of them were mining the same territory, one through pop culture and the other through fine art. People were often shocked to learn that Adrian was heterosexual. He was married until his death to ‘Miss’ Linda, his wife of over thirty years and a fellow wrestler. But he always appreciated the company of gay men, and was at ease in that community. He also became a gay pin-up (unbeknown to him) after he modelled for bodybuilding magazines in the early 1960s, which were essentially a form of very soft pornography. He was always playing with his own image.

Adrian had an incredible force of willpower and self-belief. He was absolutely single-minded and massively narcissistic; he had to be. He ran away from home and the coalmine at the age of sixteen to make a life for himself. He saw himself as a superhero and would often say that he was going to live forever; in his mind, he was immortal. Adrian lived his childhood dream and became this larger-than-life character dressing up in amazing outfits that he designed; his costumes were of such high quality that he also made them for others, including Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler (2008). He was consummately creative but the greatest artwork, of course, was himself. His body was a sculpture and his life was his performance art.

Five years ago, Adrian moved back to Brynmawr in Wales, where he was born. He came to represent society’s changing attitudes to industry, identity and entertainment. He lived it all. He wanted that photograph at the mine with his father because he hated the place and the culture. He wanted to show them what he’d made of his life. I believe it is one of the most important photographs taken in postwar Britain. It’s a prophetic image of a world in flux. Adrian showed them the future.

Jeremy Deller is a Turner prize-winning artist. He represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2013. So Many Ways To Hurt You: The Life and Times of Adrian Street (2010-2012) is available to watch online