From 1952: the art critic writing on a 1952 exhibition at London’s Army and Navy Stores of the self-taught ‘painter of genius’ Affandi (1907–90), and musing about the lessons we can learn from art created in the context of another culture and another place

Apart from the 1945 Picasso show, this is the most important contemporary exhibition seen in London since the war: important not only because Affandi, who was born in Java in 1910, is a painter of genius, but also because it indicates the type of work and the attitude which lie behind the new emerging culture of Asia, and because we in Europe will finally have to learn from that attitude.

But first a warning: about a dozen of Affandi’s fifty canvases are badly erratic and incoherent; also, all of them suffer the disadvantage of being unstretched and unframed. Personally, I believe both these facts to be constructively significant. They must, however, be allowed for when most of us in our present situation tend to be negatively critical and conservative. Nor do I wish to imply that I am above such faults. If I feel and write decisively about Affandi’s work, it is only because during the last two months I have had time to study it.

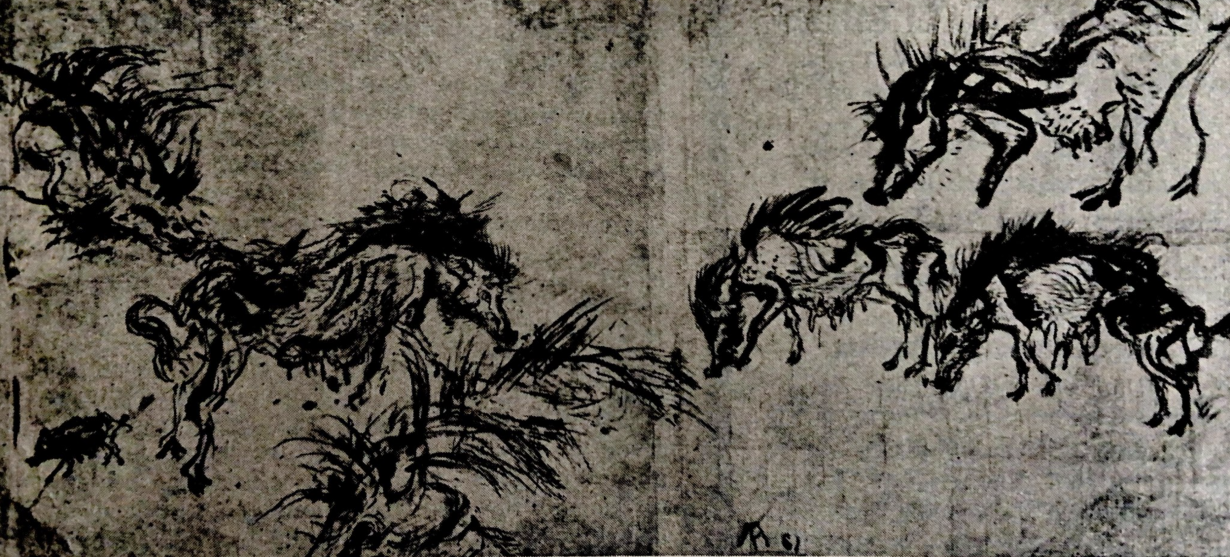

Most of the pictures are fairly large and are painted on coarse canvas. The pigment itself is usually thick and often applied in line strokes which literally appear to have hit the canvas, and, having hit it, to have been drawn irresistibly into the orbit of the forms and spaces portrayed. Or more accurately, the magnetic process appears to work both ways: the tension of the paintings is dependent on the lines and colours both attracting and being attracted by the development of the presented forms. Or again, to put it in an abstract way: the form and content of these works is indivisible. Their colour is bright, but violent and dignified rather than gay. Their subjects range from landscapes of rice fields, cities and mountains to portraits of the artist’s family; from paintings of animals – buffaloes, horses, boars, to paintings of the people to whom the artist has a complete, unselfconscious loyalty – rickshaw drivers, street musicians, republican soldiers, beggars, serious students. There are also on show a number of extraordinary drawings whose calligraphic quality is oriental, but whose grasp of particular form and expression is more reminiscent of Rembrandt or Goya.

Yet what makes any description of these works inadequate (Expressionist is the only label that appears to fit, but doesn’t) is that they are different in kind from anything we are accustomed to seeing. Not because of their exotic content – far from it: looking down one of these street scenes, one has no feeling of being on an unfamiliar set of values. Broadly speaking, ‘Art’ in the West has become inflated at the expense of life. Aesthetics have triumphed over vitality. These paintings redress the balance. They are the result of participation rather than contemplation, action rather than introspection. They are not concerned with Taste, for Taste completes and isolates. (This, I think, is the significance of the canvases being unframed and of a few being badly organised and uncorrected.) Instead, they are concerned with the continuity of life, the necessary continuity of being able to risk achievements. One could argue that such an attitude means the destruction of art, that a work of art must always be complete in itself. This is true. but such completeness is only achieved by an artist who resolves his continuous, other-than-aesthetic responsibilities, never by one who rejects them. Affandi, working during historic and heroic events (the resistance to the Jap occupation and the war against the Dutch for Indonesian independence) has a profound sense of active solidarity. The public, to whom he accepts responsibility, are not those who may happen to look at his paintings, but those who make, or are implied by his subjects. It is for this reason that his pictures do not present themselves to the spectator, but turning him into a witness, confront him.

Looking at one of Affandi’s pictures, one feels that the canvas and pigment, neither cherished nor despised for their own sake, were simply the ground on which the particular situation was fought out: the lines and colours somehow miraculously expressive tracks of the fight.

Yet the proof that Affandi has resolved his responsibilities is that his work never appears to be either moralistic (in the narrow sense) or sentimental. On the contrary, its predominant quality is one of tolerance and exhilaration. Finally, the obvious: Go to this exhibition. What I have said may be irrelevant to many readers. The only thing of which I am absolutely certain is that this exhibition is a supremely important challenge. This exhibition will be transferred to the Imperial Institute, where it will be shown from June 9th–14th.

First published 31 May 1952, Art News and Review, Vol IV No 9