Nope manages to be both Spielbergian romp and elusive work of art

Nope (2022), a science-fiction western written and directed by the comedian-turned-auteur Jordan Peele, is that hairiest of things, a film about the process of filmmaking. It is also, albeit perhaps less explicitly, a film about the relationship between exploitation and the cultural or cinematic gaze, and about the circumstances that might lead to someone thinking it was better to risk being eaten alive than to miss out on their big break. ‘I will cast abominable filth upon you,’ the furious Bible verse in its first frame assures us, ‘make you vile and make you a spectacle.’ Who is speaking in this context, given that the onscreen quotation contains no direct reference to God, is unclear. Likewise, we are left to wonder who exactly will be turned into a spectacle, and – to paraphrase the tagline of another film about the risk of being eaten alive under the azure skies of the desert – what will be left of them once the credits roll.

Our main players are Otis ‘OJ’ Hayward and his sister Emerald, played by Daniel Kaluuya and an effervescent Keke Palmer, and they are animal wranglers, operating the only Black-owned horse farm in Hollywood in the wake of the recent and mysterious death of their father. Instantly, the dynamic between the two siblings is established: OJ, taciturn and stoic, is reluctant to engage with their obnoxious human clients on an advertising shoot, focusing all of his attention on the stallion he is training; Em, arriving late, launches immediately into a peppy, goofy, thousand-mile-an-hour safety presentation that culminates in an advertisement for her other skills, which include singing, acting, modelling, and catering. Haywood Hollywood Horses, she explains, have a unique connection to the industry, and that connection is familial: the first ever moving image was a 19th-century assemblage of photographs by Eadweard Muybridge, featuring a Black jockey on a horse, and that jockey was OJ and Em’s great, great, great grandfather, Alistair Haywood. “Since the moment pictures could move,” she chirps, striking a pose like a spokescartoon in a backwards baseball cap as if she’s said this several hundred times before, “we had skin in the game.”

A story about the direct descendants of the first actor, stuntman, animal wrangler and technical star in cinematic history, and perhaps about his experiences as a Black man in the earliest moments of that industry, would be compelling enough in and of itself to justify a decent runtime. Peele, though, has other ideas – a wealth of them, jostling thrillingly and eccentrically with each other, the result being a film that somehow manages to be at once an entertaining Spielbergian romp, and an elusive work of art. To fully describe the plot of Nope is to neutralise its power to surprise; still, I believe that the film is a great achievement, either in spite of or because of its shagginess and strangeness, and as such I can think of no other way to recommend it than by outlining some of the ways it works its deranged magic.

Here is the sequence of events that sends us tumbling down the rabbit-hole, or, more accurately, sucks us up into the belly of the beast: at the advertising shoot, somebody holds a mirrored VFX ball to the horse’s eyes, and the horse – seeing itself, perhaps confused or perhaps mistaking its own reflection for a predator – panics and kicks, leaving the Haywoods short of yet another job, and even shorter on hard cash. That a mirror, or a screen, can have transmogrifying and life-altering powers is a common theme in Nope; down on their luck, drowning their sorrows at the ranch, OJ and Em see something impossible-seeming in the clouds, and when it dawns on them that it must be a UFO, they decide to shoot first and ask questions later. They need “the money shot,” Em grins, loading her shopping cart with security cameras. “The undeniable, the singular – the Oprah shot.”

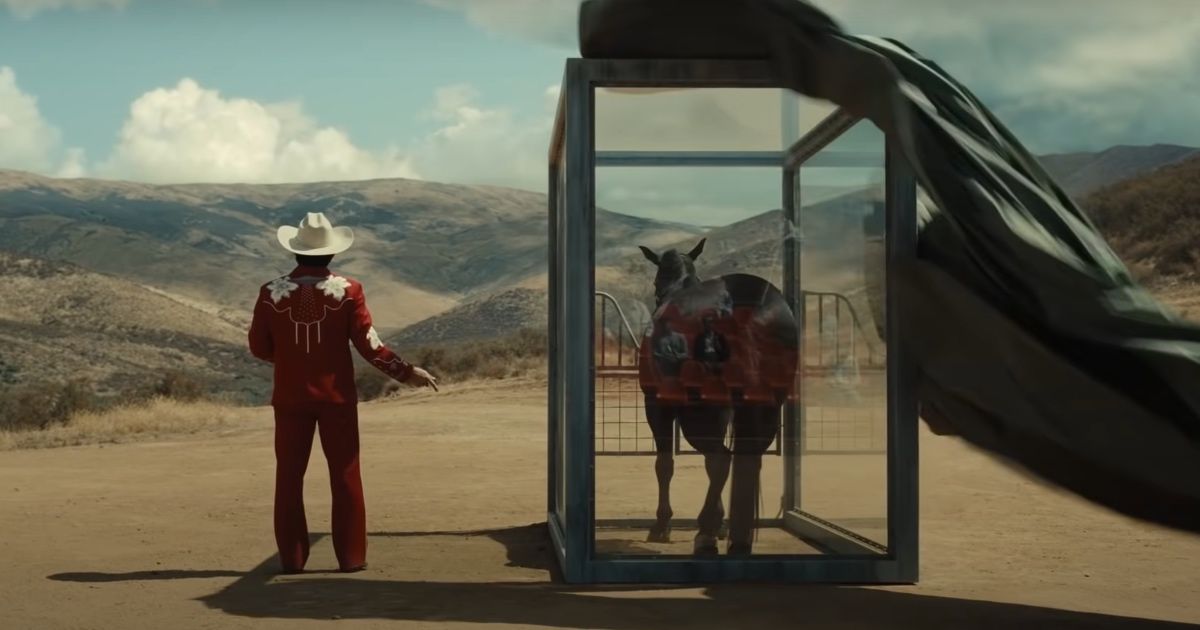

Even once it becomes clear that their new guest has definitely not come in peace, both brother and sister maintain that obtaining footage must take precedent over their personal safety. As decisions go, this is prima facie bonkers, and would leave the audience struggling to suspend their disbelief if we did not have prior knowledge of the Haywoods’ financial and professional situation, built on the slippery foundations of a legacy that might have allowed for Hollywood nepotism if they had been white, but which instead has furnished them with few benefits other than the opportunity for Em to coin a catchphrase. A similar dogged obstinacy characterises their neighbour, an Asian-American former child star named Ricky ‘Jupe’ Park (Steven Yeun, making a strong case for a men’s magazine cover-shoot in which he’s outfitted entirely in Nudie-style rodeo suits). Jupe once played the adopted son in a dumb but popular sitcom in which his primary co-star was a chimpanzee named Gordy, and that sitcom was abruptly cancelled after violence broke out on its set. Peele brazenly opens Nope with an extraordinary scene of Gordy, soaked in blood, wandering around a soundstage made to resemble a family home, and he adds one permanently unexplained, maybe magical-realist touch: the abandoned sneaker of a child, who lies torn and beaten with her face entirely out of view, standing upright on its toe as if worn by a ghost en pointe.

More extraordinary still is Peele’s refusal to point out this eerie tableaux’s actual connection to the plot for what must be the first thirty-ish minutes of Nope’s runtime – a relative risk that I think sealed my fealty to the film, which I watched in a commercial multiplex as if it were a conventional blockbuster. When Em and OJ drop in at Jupe’s cowboy theme park, ostensibly to sell him a horse, Em’s excitable nostalgia about Jupe’s former career encourages him to reveal another of his income sources, and he lets them into a locked room filled with lit vitrines housing remnants from the set of Gordy’s Home!, one of which is the child’s plimsoll from the opening scene. Em, sweetly tactless, presses him for information about what actually happened on that fateful day, and Jupe – his voice so smooth it suggests that he has rehearsed the monologue, but his gaze so distant that we know he is remembering something awful – tells her she should watch a sketch from SNL about the incident. “Chris Kattan,” he breathes, his eyes narrowing in what might be mirth but also might be terrible psychic pain, “crushed it.”

Jupe, in other words, can only bear to revisit his on-set trauma through the lens of a fictionalised sketch, just as he has chosen to experience life itself in the uncanny surrounds of a mocked-up Wild West town, a simulacrum of traditionally white American history that is so false and flimsy that it might as well be made from cardboard. If this bit of commentary about our mutually-sabotaging relationship with the screen and its mythology is a little paging Guy Debord!, it is also simply one of many similar devices, employed in a harum-scarum manner that prevents the film from coalescing into a didactic message movie in the manner of, say, Alex Garland’s recent Men (2022). As he demonstrated with The Sunken Place in 2017’s Get Out, Peele has an eye for the cinematic, and the line between spoofing the majesty of classic Spielberg and actually recreating it is very, very thin.

You want to talk about another thing that’s prima facie bonkers: how about making a movie that is in part a critique of the tyranny of the spectacle that also happens to house several discrete images that are almost impossible to describe without resorting to the word ‘spectacular’? If I appear to be struggling to explain just what Nope is trying to say, it may be because Peele does not totally explain it, either; this is fine by me, since I would rather a film have too many ideas than too few. An auteur should be an artist, and not an interpreter, and if Nope is Peele’s response to the historically exploitative relationship between the media and non-white performers, it is not his job to draw me, a white critic, a blandly elucidative diagram. I understand that Nope has been divisive. All I can say is that it provoked in me an immediate feeling, an instinctive stirring of the gut.

Speaking of animal instinct, look away now if you are dodging heavy spoilers: it turns out eventually that the alien ‘ship’ is not a ship at all, but an enormous creature, and as such its aim is not abduction, but digestion. OJ realises, significantly, that the alien will not eat its quarry if that quarry makes eye-contact with it, flashing back immediately to the kicking of that frightened horse. The idea that alien life forms would decide to behave territorially over the one Black-owned horse farm in Hollywood is, in itself, a dark joke: even extraterrestrials, Peele seems to dryly suggest, think of Black land as being up for grabs, colonialism and racism proving to be not simply global sicknesses, but intergalactic ones.

When OJ points out, vis-à-vis the rule that they must not look at the alien, that abiding by an untameable predator’s behavioural codes is the best way to survive, I thought back to Emerald’s presentation for that snotty crew – her eagerness to impress, her well-rehearsed friendliness, and the way Kaluuya, in the background, allows disappointment and embarrassment to flicker across his face. Predatory human beings have their behavioural codes, too, and some of them are abominably filthy. The film’s title, at first rumoured to be an acronym for ‘not of planet earth,’ is intended, Peele has said, to mirror the ideal reaction from his viewer to its most hair-raising scenes; it is what OJ, in a shot that plays homage to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), murmurs gruffly as he sees that unfamiliar form hovering right over his truck for the first time. Do note, though, that it is also what Em says immediately after asking the assembled film crew whether, given that most people in the movies know who Eadweard Muybridge is, they know her great, great, great grandfather’s name. Ultimately, Nope presents a fantasy – a science fiction – in which it is the one gawking, the consumer, who ends up being consumed.