Two new books on antechambers and atriums explore the politics of transitional architecture

Since moving to Germany a few months ago, a memorable part of my life has been ticked away in waiting rooms. Spend enough time in Wartezimmer and you may, like me, become transfixed by the interplay of architecture and social etiquette, protocols shaped by the contours of space. It’s polite here to greet strangers in doctors’ offices, where horseshoe layouts prevail and everyone’s body is oriented towards the doorway. Briefly mistaking the latest patient for a beckoning nurse, we all spit out a taut Morgen laced with frustration, before averting our eyes to the floor once again. At the various municipal Bürgerämter, where you must register your residential address with each new sublet, it’s more common to perch in communal silence before an LCD appointment screen. A type of space that can verge on democratic at urgent care clinics, the waiting room of the Ausländerbehörde is pre-sorted by passport and politics. Once I’d arrived at this immigration office, I was put into the antechamber for spouses of EU citizens. Across the corridor was a doorway with a taped A4 sign scrawled in red biro: UKRAINE.

My summer of waiting and expectation culminated in a spell of reading. Not the glossy automotive mags that seem to litter foyers the world over, but two new books on the architecture of antechambers and atriums, both a kind of ‘antespace’ – a concept historian Helmut Puff develops in The Antechamber: Toward a History of Waiting. ‘Antespace’ denotes built environments where ‘architecture becomes experiential in a processual manner’, where ‘mobility and immobility converge’. In his ‘history of waiting’, we learn how European architecture – mainly aristocratic residences, but also the homes of the ‘middling classes’ in Baroque Rome and of the bourgeoise in eighteenth-century Paris – renovated perceptions of time and space. Between 1500 and 1800, corridors, vestibules and nested rooms proliferated; the inner sanctum of daily life was increasingly walled off from dedicated places of circulation and service. These antechambers entwine space and time in their very name: they are rooms you enter on your way to other rooms, where events occur that preface what’s to come.

Antechambers offered new architectural tools for choreographing experience through immersion and procession, and they shaped time into a technology for engineering social experience. The ground plans of the Papal Palace in Avignon, for instance, resembled a series of airlocks or checkpoints – here, ‘a person’s distinction manifested itself through spatial distances and temporal intervals’. Job seekers, servants, courtiers, merchants, diplomats and countless other professions and classes frequently found themselves in antechambers, which had a dual function: to ease the plight of the waiter and to enshrine a decorous vision of the awaited. These spaces regimented social interactions, ‘they solicited responses, guided people, and encouraged certain comportments, imposing a particular gait or affect on those who spent time in them’. In perhaps his most intriguing idea, Puff claims that actively waiting in anticipation of a meeting is ‘an integral part of sociality in stratified societies, whether at court or in urban communities’. To await someone for prolonged periods is to physically experience their importance through a scarcity of access. And yet, the seemingly ghosted had recourse, for excessive waits were taken as proof of ‘unjust rule’ in medieval and early modern Europe, spelling the beginning of the antechamber’s demise.

All forms of waiting – bar damnation – must eventually come to an end. ‘Antespatiality’ persisted after 1800, claims Puff, ‘yet wherever possible, the plight of the waiter was masked or lightened, especially for the well-to-do’. With the decline of the old regimes in Europe, ceremonial waiting became an antiquated practice. Evolving economic systems once again restructured space-time – when time is money, few have enough to kill.

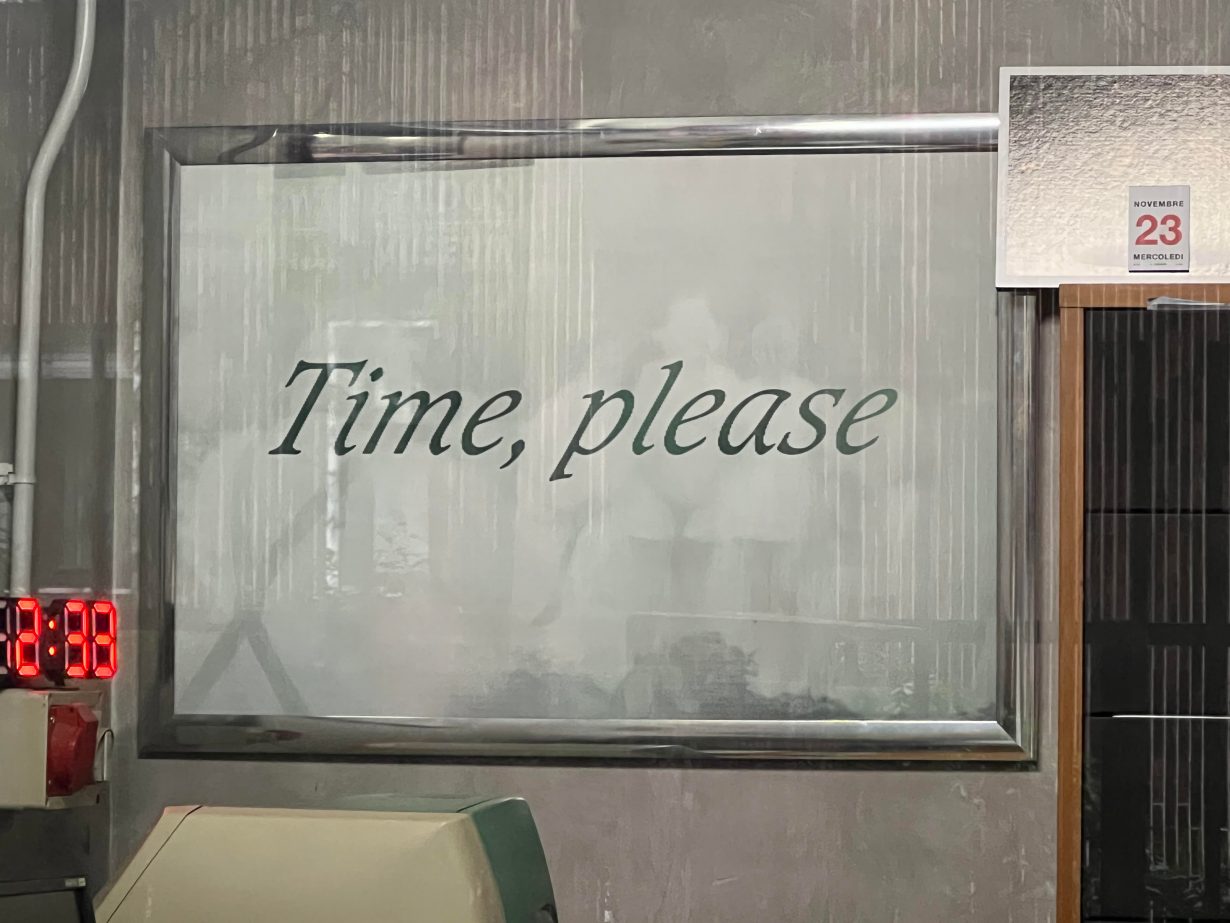

Does time operate differently in different types of rooms? Marc Augé’s shopworn neologism of the ‘non-place’ has become a shorthand for capitalism’s tendency to erode distinct places, leaving behind smooth, forgettable zones: the interstitial hotel rooms and petrol stations that recede back into indistinction once they vanish from view. But there is nothing smooth about the dentist’s reception, where time dilates like a cavity to the pulse of muffled drills, or the pathetic bardo of Zoom’s virtual waiting room, in which we long like a Kafka character for someone to admit us who may simply never come. Antespace helps name and excavate the architectural and emotional inheritance of these workaday delays. Puff’s study rebuffs the knee-jerk assumption that waiting is a form of tedium at its core. (Due to the tedious conventions of academic style, however, the same cannot always be said of his prose.) Antechambers were decorated with frescoes, tapestries, sculptures, reliefs and ornamented timepieces, whose scenes he reads as both imaging and stoking the anxieties, woes, amorous horizons and myriad other concerns that preoccupied the waiter.

Antespace experienced a renaissance in a different time and place, with a different set of demands, near the end of the twentieth century. In the mid-1980s, walking through the lobby of the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, Fredric Jameson found himself disturbed by the atrium, which seemed to impose ‘some new category of enclosure governing the inner space of the hotel itself’. Sound familiar? In Atrium, Charles Rice tracks how the atrium’s popularity accompanied a sea change in the practice of architecture during the 1970s and 80s. The story begins circa 1961, when New York building codes granted ‘floor area bonuses’ to commercial developments in exchange for publicly accessible space. Built on a court model, the atrium redefined the relationship between public and private – the form made private buildings into de facto retaining walls, which enclosed a quasi-public void, often ‘interiorscaped’ with plants and gardens. More than an arrangement of the visible, atriums are perhaps best observed as an ordering of negative space. When ‘sick building syndrome’ – a kind of Havana syndrome avant la lettre, where coworkers succumbed to manifold illnesses with no clear cause – mystified regulators and ventilation designers alike in the mid-1970s, the atrium’s plenum of air was championed as a source of climactic variation, which could be recirculated into smaller rooms for health or energy conservation.

Like Puff’s antechamber, the atrium fascinates Rice for the economic and social relations that it enshrines. It marks a ‘particular spatial threshold in corporate architecture, a designed material intervention that promoted the core of corporate work as a certain kind of self-managed “freedom”’. This freedom is often anything but. Discussing Herman Hertzberger’s Centraal Beheer Office Building in the Netherlands, Rice quotes office space planner Francis Duffy: ‘Could it be that the whole building is an enormous red herring, cynically erected by management to divert worker attention from real issues? By permitting at very small expense a certain amount of autonomous interior decoration, has management bought peace and the reputation for being progressive?’ In the atrium’s playbook, Rice sees the hand of neoliberal strategy. It comes as no surprise to the author that Google purchased the James R. Thompson Center in Chicago in 2022. The tech company’s intention to refashion this iconic 1985 building and its 17-storey atrium into an environmentally friendly home for a ‘flexible, hybrid workforce’ encapsulates Rice’s argument, as the metrics of efficiency and ‘building performance’ come to trump architectural significance, spatial indeterminacy replaces programmatic intention and organizational strategy hides within the rhetoric of user accommodation.

The Antechamber and Atrium employ a similar organisational strategy of their own, reading their respective transitional spaces as products of waxing and waning economic regimes: early modern courts and their aftermath; Reaganomics and Thatcher’s ‘deregulation agenda’. These academic studies can also be viewed as products of economic history. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and global lockdowns, when many of us spent months isolated in rooms – and as quasi-public environments like atriums become depopulated or repurposed in the era of hybrid work – these spaces gained a certain visibility through obsolescence. Both books struggle to discover what exactly it was like to be in these rooms during their heyday. Of course, this is less the fault of the authors and more a result of what humans choose to record. Our waits are rehearsals for the ultimate appointment; we pass through rooms inside of bodies that only hold us temporarily. We might as well look around and say what we see.

Atrium by Charles Rice. MIT Press (hardback), $44.95

The Antechamber: Toward a History of Waiting by Helmut Puff. Stanford University Press (paperback), $30

Hunter Dukes is managing editor of Cabinet magazine and The Public Domain Review.