An exhibition at The Drawing Centre of hundreds of works from the artist’s private collection seems most interested in establishing the street cred of KAWS himself

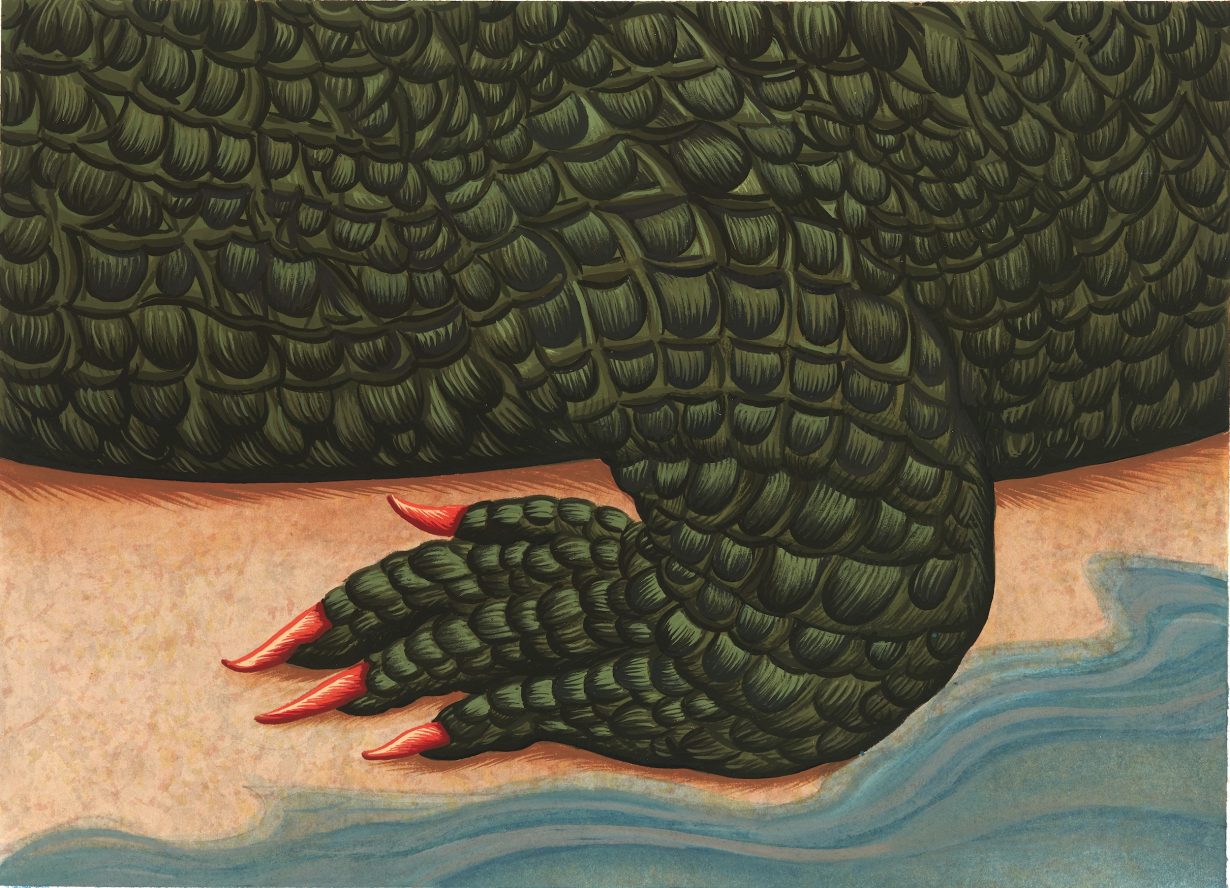

Brian Donnelly came up writing graffiti in New York and New Jersey in the nineties, throwing up the tag KAWS while pulling down a paycheck as an animator for family-friendly media companies. Under the same moniker, the Brooklyn-based artist, now a long way from his street art start, famously appropriates Spongebob, the Simpsons, the Muppets and their ilk to produce collectible toys, hard-edge paintings and large-scale public sculpture. His Mickey Mouse-inspired Companion figures – cast vinyl, wood, or bronze sculptures with crossed-out eyes and crossbones through their heads – are some of the most salable artworks in the world. KAWS created the cover art for the deluxe edition of Kanye West’s 2008 album 808s & Heartbreak and collaborates on streetwear with brands like Nike, Comme des Garçons and DIOR. Drake, Pharrell Williams and Justin Bieber collect KAWS, yet casual enthusiasts may not know that KAWS is a collector himself, and a good one. His trove of over 4,000 items in diverse media amassed over the last twenty-four years is especially strong in work by graffiti artists, self-taught and outsider artists and artists like Jim Nutt, Peter Saul and Tomoo Gokita who tend towards the bizarre, kooky and surreal.

The Way I See It: Selections from the KAWS Collection at The Drawing Center centres two recreations of KAWS’s office. On Instagram, this is known as the place to get a picture taken after a studio visit with KAWS. The recreations are installed back-to-back in the middle of The Drawing Center’s main gallery and protected behind a partial glass wall. In these contemporary period rooms, artwork is hung salon-style from floor to ceiling. Japanese artist Haroshi’s monster toys constructed from recycled skateboard decks sit on a high-end coffee table KAWS designed. Small sculptures by KAWS and others abound on other designer tables and the floor. 1960s American folk-art-inspired assemblages by H.C. Westermann hold the sides of the office rooms like museum guards. According to the exhibition catalogue, KAWS wanted to build these installations to show how he lives with the artworks he owns.

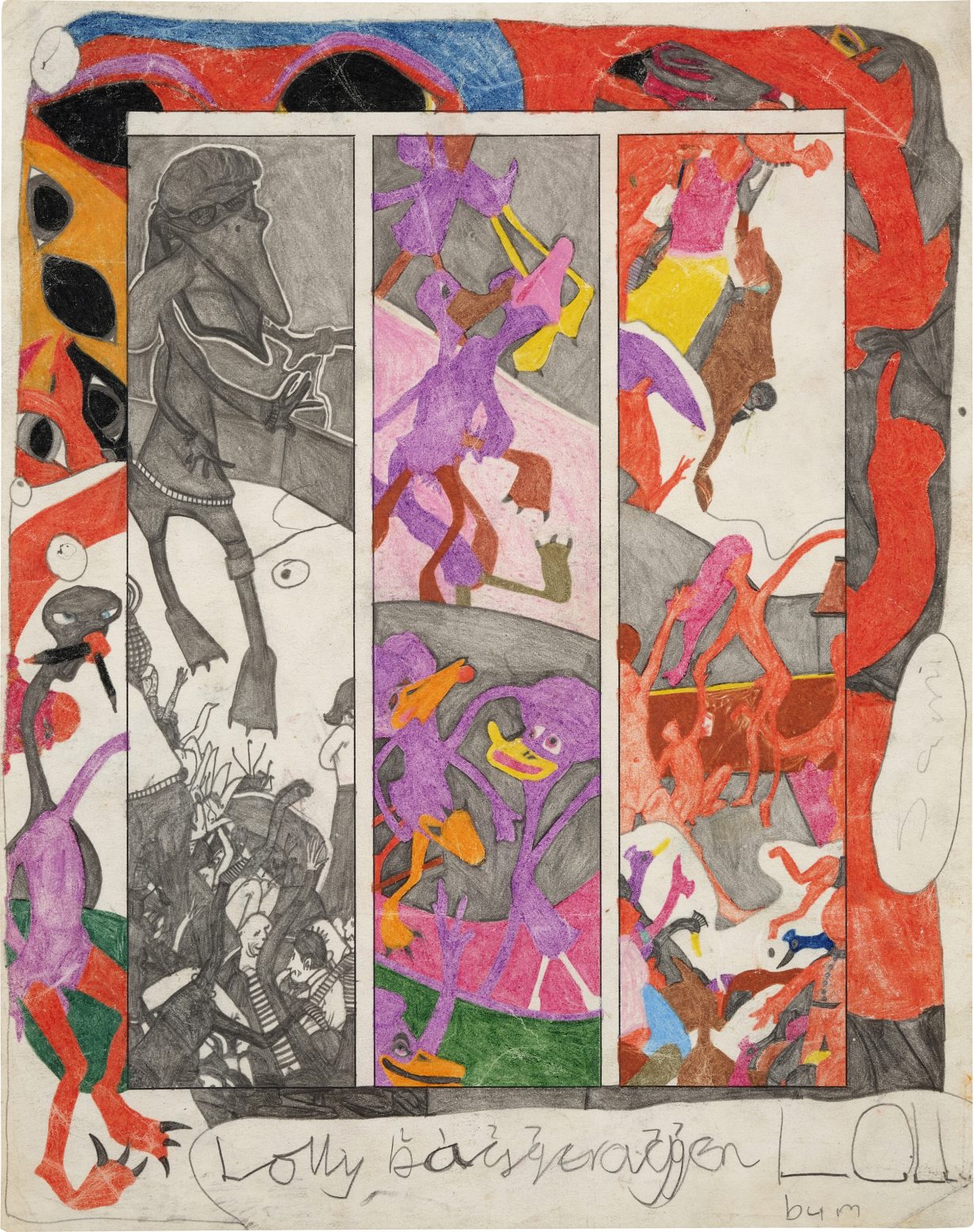

The show contains about four hundred works. Outside the ‘offices’, they’re hung more conventionally. There are interpretations of Mickey Mouse by Joyce Pensato, Raymond Pettibon and others, sketches from the 1970s and 1980s by New York graffiti artists like Lee Quiñones, DONDI and Rammellzee and labour-intensive drawings often using coloured pencil by artists like Simone Johnson, Helen Rae, Yuichiro Ukai and Nicole Appel, who work, or have worked, at art studios set up to support neurodivergent artists. More mainstream picks include a 1971 Pablo Picasso harlequin head in ink and pastel on cardboard, a Willem de Kooning charcoal that resembles the lumpy bronze figures he was making around the same time and Nicole Eisenman’s pencil-and-ink nude, Math (2017).

Seeing as the catalogue focuses on KAWS, with only short bios of the artists in his collection – and not even all of them – The Drawing Center and the artist would have done well to focus The Way I See It by offering an overt theme and more museum-style interpretation in the galleries. This is especially the case when the works on view undercut the ethos of the exhibition. For instance, the exhibition materials assert that the show offers a historical corrective by defying art-historical hierarchies and embracing diversity, but an undated work in an upstairs gallery by R. Crumb, a cantankerous and sometimes backward hero of underground comics, suggests otherwise. Titled Mr. Natural Takes a Vacation, it shows two racist minstrel-type representations of Black women. A wall label giving historical context would have been helpful here.

Ultimately, the absence of a curatorial hand betrays an institutional strategy to court a celebrity artist wishing to establish his own street cred as an artworld ‘outsider’ and thereby to attract his many fans to their programme. As is, the creators and creations featured in The Way I See It risk being lumped together as merely influences and inspirations for KAWS. What results is an emptying out, not an equitable leveling out. Marcus Civin

The Way I See It: Selections from the KAWS Collection at The Drawing Center, New York, through 19 January