A new videowork by Liu Chuang, full of allegory and representation, posits an alien invasion against the beauty and lost opportunities of Earth and its dumb inhabitants

Taking past, present and future China as its playground, Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018), a 40-minute, three-channel (think super-widescreen) videowork by Shanghai-based artist Liu Chuang, is a meditation on victims and oppressors and the interrelated subjects of power, profit and control. In both human and nonhuman arenas. If there’s such a thing as going ‘viral’ in the world of art (tricky, given that the unspoken economy behind art is built on scarcity), then Bitcoin Mining seems to have achieved it, seemingly on a continuous trundle through worldwide biennials, among them the Asian Art Biennial, Taipei and the 5th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, Ekaterinburg, in 2019; the Dhaka Art Summit, 2020; the Seoul Mediacity Biennale, 2021; and most recently finding a corner in this year’s Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale in Riyadh.

The work uses a blend of found and filmed footage, extracts from popular and unpopular cinema, and citations from academic literature and pop culture to draw out its core themes. By entangling fact and fiction, time and space, Liu poses bitcoin miners as practitioners of traditional transhumance and, conversely, ethnic minority cultures as dead museum relics. As a viewer, one minute you’re pondering an analysis of Zhou dynasty (c.1046–256 BCE) economics, the next you’re considering the relationship of Mongolian wedding dresses to the aesthetics of the Star Wars movie franchise, all the while wondering what any of that has to do with cheap karaoke machines, colonial telegraph wires, a tendency to put big statues next to big dams and why some human beings (ethnic minorities) are continuously treated as if they were (threatening) aliens. Like most great art, the work performs a perfectly judged tightrope act, guiding viewers safely across the fine line that, to a purely academic mind, would separate the profound from the ridiculous. While nevertheless keeping us entertained with the sensation that it is continuously tottering on the brink of the latter.

Liu’s latest videowork, the near-hourlong, three-channel Lithium Lake and Island of Polyphony (2023), deploys the same techniques as its predecessor and debuted last November at Antenna Space, Shanghai. Like Bitcoin Mining, its title links two apparently disparate subject matters: the production and extraction of an atomically unstable alkaline metal (best known for its use in smartphone batteries) and a musical texture made up of two or more equal but independent melodies. During the mid-sixteenth century, in Italy, the Bishop of Verona forbade the form from being performed in convents on the basis that, unlike monophony (which became the dominant form in Western music), it was morally dangerous and encouraged individual vanity among the nuns. Some of these latter, however, continued to write, in secret, polyphonic hymns, and when polyphonic singing is part of Liu’s video it is notably performed by Lithuanian folksingers and Mbuti tribeswomen. While Europe is not the primary target of Liu’s work (other than as a colonial force, ultimately responsible for many of the problems related to capitalism and globalisation that plague the global majority today), Lithium Lake proposes the persistence of related fears and proscriptions. Not least in an intriguing segment on Project Cybersyn, a decision-support system developed by British cyberneticist Stafford Beer and deployed during the early 1970s by Salvador Allende’s shortlived socialist government in Chile to create a managed economy with ‘almost instant’ feedback (via Telex machine) from factories and service industries. This polyvocal form of socialism was crushed following an America-backed coup and Allende’s subsequent death in late 1973.

Lithium Lake also picks up themes that rumbled through Bitcoin Mining: the link between the control of water and the exercise of power, the relation, with respect to control, between silence and the lack of it, the more general links be tween ecology and economics, and an obsession with scenes from Steven Spielberg’s movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1979), in which humans attempt to communicate, through light and sound, with an alien mothership. The result is a paean to diversity in the face of humanity’s blinkered drive down a highway to ecological hell. With song as its metaphor and representation as its driving force, its narrative blends science-fiction movies and novels, a long-extinct hominid ‘discovered’ in 2002, an incarnation of the Buddha whose compassion led him to become a meal for a tigress, the theories of historic and contemporary economists and physicists, seventeenth-century philosophers, twentieth-century ethnomusicologists and historians, the chief adviser to French president François Mitterrand and a focus on Earth’s flora and fauna.

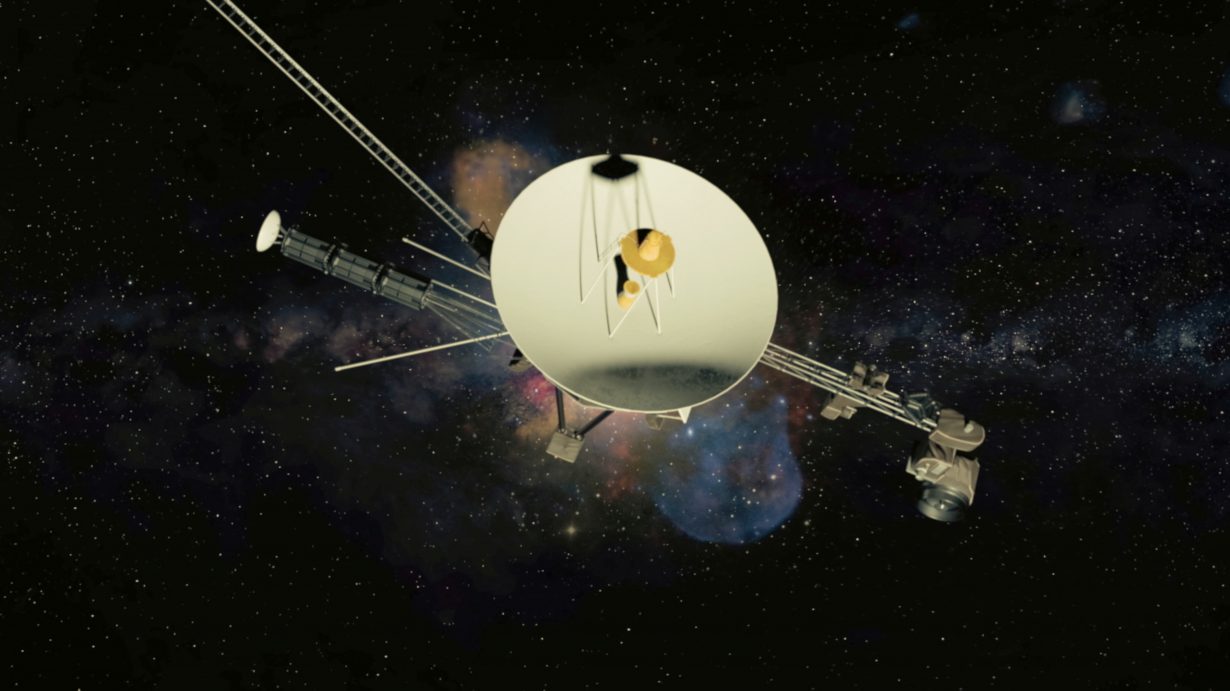

It starts, however, with a homage to Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968): a bone rotating through the air, presumably symbolising, as in Kubrick’s film, the discovery of tools, the transformation of apes into humans and the idea of progress and its accompanying violence. This time, though, the bone has holes drilled into it, suggesting more a flute than a club. In keeping with that, the shot of the bone cuts not to a rotating space station, as it does in 2001, but to a CGI of the Voyager 1 spaceship (launched in 1977 and now the most travelled humanmade object in the universe, hurtling towards nowhere in particular through interstellar space) and the Golden Record attached to it. The Golden Record is what it says it is. Once an alien civilisation has worked out how to play it (instructions on the golden packaging, which also contains a guide to the location of Earth), they will hear greetings in a number of languages, a speech from Kurt Waldheim (back then Secretary General of the un) and a general introduction to the diversity of life on Earth (in both sound and images). A diversity, Liu’s video goes on to suggest, that is rapidly becoming extinct.

From there, Liu channels the contemporary Chinese science-fiction writer Cixin Liu, and in particular the plot of his novel The Three-Body Problem (2008; translated into English in 2014 and this year adapted as a controversial Netflix series) and the related ‘dark forest theory’, which asserts that the first thing an alien race will do, on discovering the existence of another, is to destroy the threat. A theory, effectively ‘silence is golden’ – an ironic riposte to the Golden Record – that was also espoused by physicists such as Stephen Hawking, and which reflects the policy of most earthbound ‘superpowers’ throughout history. One of the limits of science fiction, perhaps, is that we can only, really, imagine what we know: ourselves. If we look to nature, Liu suggests, while projecting images of tiger moths evading predation by bats, aided by a soft, sound-absorbent fur and an ability to project the false sounds of other elements in the natural world, we might learn a thing or too. Even if the rule of this jungle is that every living thing is afraid of unfamiliar forms. Today, the tactics of the tiger moth are deployed in the creation of light shows designed to make ugly largescale infrastructure – here dams – less unpleasant and more entertaining.

Back in the world of Cixin’s novel, that alien race is the Trisolarans, who upon discovering the existence of Earth set about to destroy it. However, on realising that it will take them 400 years to reach their target, by which time they surmise that humans will have evolved their technology beyond that of the Trisolaran’s own at the time of launch, they send a computer, the ‘Sophon’, as an avant-garde tasked with slowing down and confounding any technological development (particularly when it comes to particle physics and energy production), and generally spying on Earth. In Liu’s film, the Sophon, which has transformed into a female human, acts as our largely mute guide (words are provided via a narrator) through the rest of the artwork. And what she discovers is that humanity is doing a pretty good job, through the destruction of other species and Earth’s atmosphere and the natural environment more generally, of retarding itself. In relation to which, Liu evokes economist W. Brian Arthur’s ‘lock-in’ theory, by which increasing-returns technologies that ‘by chance gain an early lead in adoption’ corner the market to the extent that no one continues to think about alternatives (in Liu’s video this relates to the dominance of carbon and then lithium technologies). Similarly, in Lithium Lake the discovery of whale song is the accidental byproduct of the paranoic silence on Cold War submarines: woven together with ethnomusicologist Joseph Jordania’s theory that humans sang in the trees and became silent on the plains, progress is gradually related to silence, alterity to song.

By the halfway point of the video, the Sophon has discovered and started dealing with its own redundancy, smoking and staring at a reproduction of Caspar David Friedrich’s classic depiction of the Romantic sublime, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818), touching and feeling the natural world in what, perhaps, are the alien equivalent of its moody teenage years.

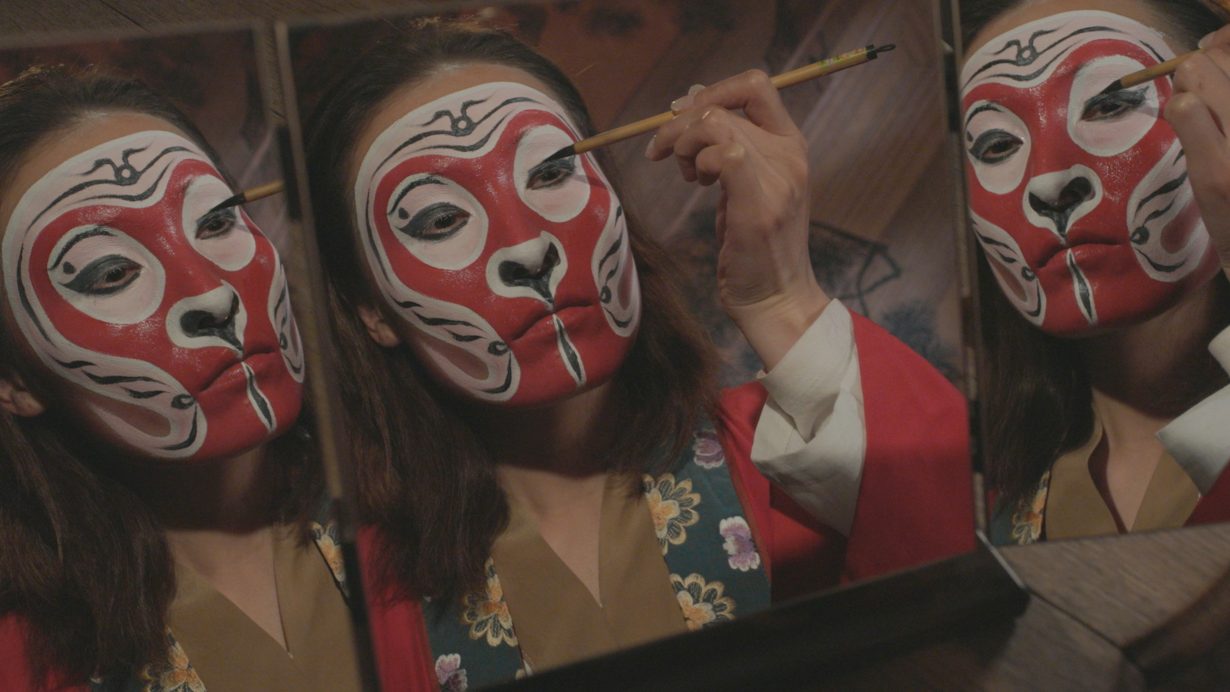

Perhaps what’s most intriguing about the film is that, like the Golden Record, much of the view of Earth presented by Liu is through representation. A Ming-dynasty scroll painting is used to depict urban demand for managed nature in the form of gardens. Hu Huai’s tenth-century painting Bestiary of Real and Imaginary Animals is animated to depict the extinction of species. Vintage movie footage of a tiger on the prowl is presented in the context of a traditional theatre setting. In the midst of her musings, the Sophon is applying face paint as if to perform a Chinese Opera version of the mythical Sun Wukong; Edgar Degas’s 1875–76 painting Dans un Café becomes the trigger for an exploration of the spread of silence and distinctions of class; coins, with the heads of Ferdinand VII, King of Spain (1784–1833), and his predecessor Charles III (1759–88), become a cypher for colonial exploitation. The entirety presenting art as a space of truths and imagination. Towards the end of the film, Liu cites French economist and scholar (and adviser to François Mitterrand) Jacques Attali, who asserted that representation was a power that once only belonged to God. Today, seven billion mobile phones have changed that, Liu suggests. We’re subject to an uninterrupted stream of messages, but don’t really speak. Although we could.