For all of its big ideas of futures and freedom, the 36th edition, The Oracle, is altogether something smaller and more diaristic

In some respects, this biennial began with a first dispatch dropped on 6 December 2024, in Mousse, six months to the day before its physical opening. While many biennials are developed in the utmost secrecy, curator Chus Martínez offered the opposite. In the following 25 weekly chronicles, Martínez’s guiding principles – health, love and wealth – weaved connections, welcomed other words, accrued meaning, convened 25 artists, became incantations and eventually assembled around four sites to form a multi-accented chorus.

Martínez’s spatial choreography for the biennial, themed as The Oracle: On Fantasy and Freedom, echoes her diaristic approach: it traces a short itinerary between Tivoli Park and the Ljubljanica river along city streets, bridges and shadowed paths. At each of The Oracle’s main venues we are greeted by one of Silvan Omerzu’s installations of puppets/automatons and a triad of printed texts – a curatorial introduction, a short poem by Svetlana Makarovič and a pedagogical prompt under the heading ‘conversations with the oracle’. This potent curatorial gesture, a material-textual cocktail meant to orient visitors and foster diverse approaches to the biennial, quickly becomes contrived, the overabundance of words cacophonic.

Kathrin Siegrist’s installation A Shade We Share II (2025) billows above the entrance to the Museum of Modern Art (MG+), the biennial’s main venue, extending an invitation to walk up the canopied steps. As it gently interacts with winds, Siegrist’s colourful inverted pyramid of repurposed parachutes and dangling cords playfully offsets the grey permanence of the stately modernist building. In the first gallery, Ajša Pengov’s humble, fist-sized 1951 puppet Žogica Marogica, aka Speckles the Ball, also dangles from strings to meet us eye to eye. Borrowed from Czech puppeteer Jan Malík’s popular 1936 fable about the emancipatory power of intentional community, Žogica conveys the conceptual core of the biennial.

For the two-channel installation Open World (2025) presented in the next room, Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei have reprgrammed a BAD 2 weaponised robotic dog to be a pet. On the smaller flatscreen we meet Yarik, a young gamer displaced by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, who remotely operates the talking dog from his console. Behind him, the larger projection follows the dog’s journey through the place Yarik fled and his delegated interaction, in which longing weaves itself into play, with the family and neighbours he left behind. Here, the robot, a wireless technological puppet, becomes a vehicle to rehearse imaginary scenarios and to forge freedom-oriented human-animal-machine solidarities. Nearby, Noor Abed’s A study of a stick: movement notations and notes on defiance (2025) combines detailed drawings of a stick, notations on its flight pattern and motion studies for throwing it at a drone. Together, the works of Siegrist, Pengov, Malashchuk and Khimei, and Abed draft notes towards freedom as they whisper an ode to survivance, reminding us that the tools and know-how for our emancipation are at hand.

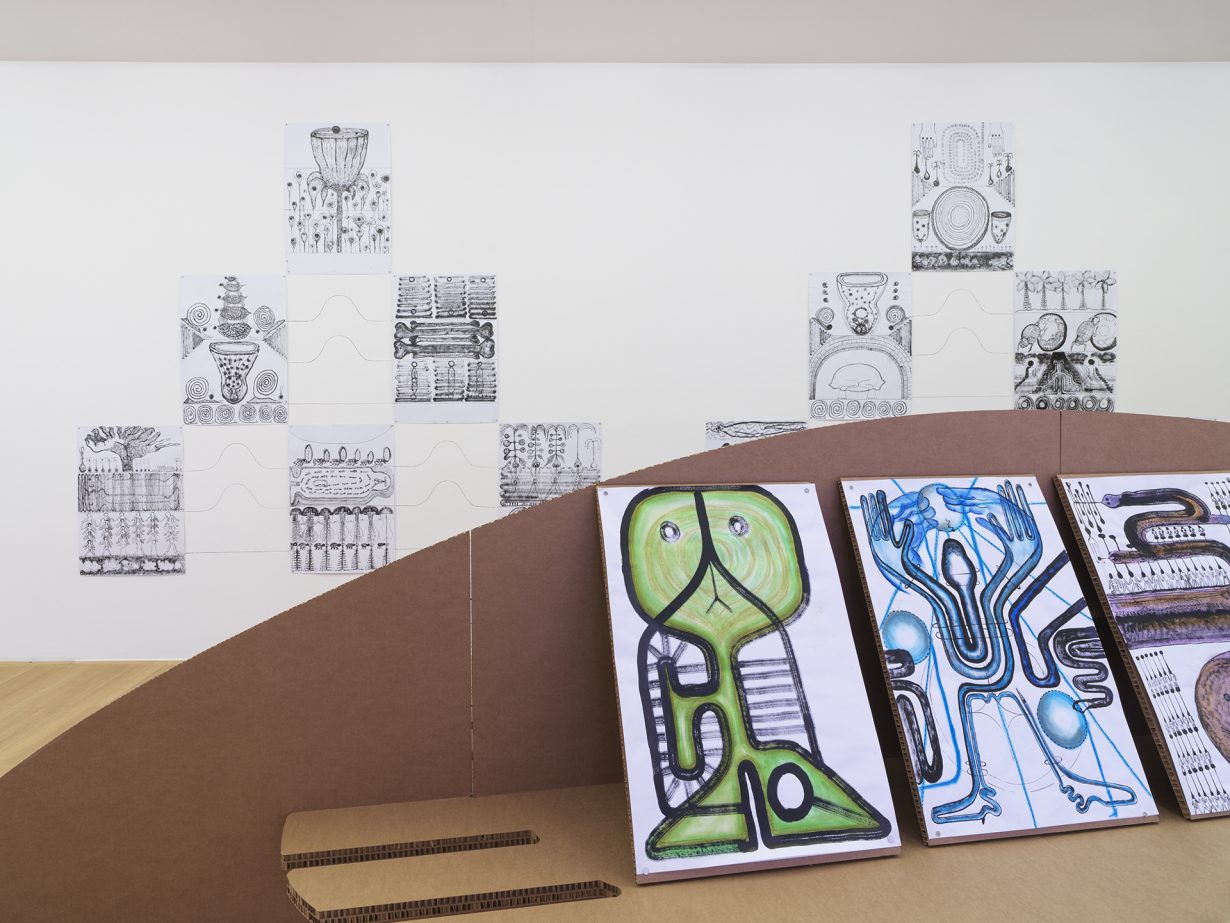

Immersing visitors in more-than-human worlds, the elegant cohabitation of Nohemí Pérez’s monumental charcoal and embroidery on canvas with Jane Jin Kaisen’s two large projections calls on us to slow down and recalibrate our senses. Both artists enlist interscalar play. Pérez’s diminutive, intricately detailed and colourful embroidered animals and insects amplify the majesty of both her depicted trees and of interspecies entanglements. Kaisen’s use of sound and image immerses us in a similar experience, albeit with time, shuttling across planetary and cellular times, through past, present and future. Eduardo Navarro’s space is both a shrine to seals and a humorous critique of the theories of nature that colonialism has ensconced in our imaginaries. Oceanic Altar (2025), a room-size cardboard sculpture of a seal, displays ink and pastel drawings imaginatively evoking a marine mammal viewpoint. It is surrounded by The origin of the Origin of all transformation (2025), an installation in which three pyramid-shaped clusters of taller ink drawings on paper, connected by dotted ink lines on the wall, rewrite outworn notions of food chain, survival of the fittest and natural selection.

Tivoli Castle is host to fantasy: in Gabi Dao’s two-room installation Sweet Blood in Stagnant Waters (2025), we traverse a staged assembly of suspended marionettes to reach a video in which humanoid cyborgs escaped Earth’s collapse and settled on a proxy planet where they are haunted by earthly ghosts and plagued by a deadly genetically modified mosquito and reproductive challenges. Upstairs, in Gabriel Abrantes’s four-channel video Bardo Loops (2024), two spectral avatars struggle to find the words and gestures to reach each other. CANAN’s monumental site-responsive installation Kıymeti Zatiyye (Intrinsic Value, 2025) grounds fantasy in material. Orchestrating fabric and light across four rooms, it offers a sensorially disorienting immersion into the intimate work of ideology, one stitch after the other.

At the City Art Gallery Ljubljana are two of the biennial’s standout works. From the street-level shopfront window, Ingo Niermann and Mayte Gómez Molina’s Hieroglyphs of the Monadic Age (2025) hails passersby with a colourful graphics-and-text vinyl installation and a video animation presented on large LED panel. Succinctly captioned and structured around actors, actions, transactors and monadic age, the animation offers a critical primer to autonomy in our post neoliberal present. One flight up, Takeshi Yasura’s subtle yet expansive installation distilled (2025) plays on the intra-action of matter and concepts. It places us at the edge of a space where light, glass, birdsong, water and other materials act with each other, spill out onto the street and in the stairway, barely noticed.

The Oracle feels like a project made, first and foremost, for Ljubljana, a project guided by a politics of proximity, both speculative and grounded. It delivers on a wish shared in a January diary entry, where Martínez wondered, ‘Wouldn’t it be wild and beautiful if visiting an exhibition – an activity with only a limited range of effects – could arouse such curiosity in people that it inspires them to explore worlds closer than they think?’ For the possibility of emancipation often lies in such worlds, which are already here but not always perceptible.

The 36th Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts, Various venues, through 12 October

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.