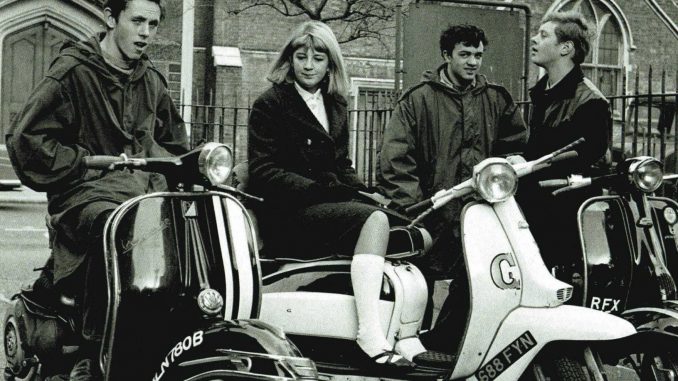

That ‘Mods’ – the sharply dressed youth tribe of 1960s Britain – should have something to do with modern art (of the 1960s) seems at first incongruous. It’s not that the two weren’t adjacent culturally and socially, but that art history and cultural history tend to keep their objects in their separate tracks – the history of painting and sculpture in one, say, and the history of fashion cults and popular culture in another. What art historian Thomas Crow essays in The Hidden Mod in Modern Art (2020) is a sympathetic and elegantly counterintuitive account of the emergence of something more like an attitude towards life; a kind of subject who was ‘devoted on an almost full-time basis to fastidious discrimination in the styling of the self’.

Crow refuses to compartmentalise fashion, design, music and art, preferring to weave these together like threads in a Mod’s knitted tie. His close-to cultural history is about individuals, not abstracted cultural or social movements, each chapter tracing fortuitous interconnections between creative minds in particular urban and institutional junctures. The tiny, hothouse world of artists, art schools, soho bohemia, fashion shops and art galleries of the 60s are here mapped in synchronicity, and the first chapter opens with Crow’s ironic recommendation that ‘it is often useful to launch an investigation into any artistic episode from an apparently marginal or inauspicious point of entry.’ In this case it’s an ad for Vince’s, a proto-Mod menswear shop in Soho. This ad, however, appears in Ark, the magazine of the Royal College of Art at its most influential moment; Ark’s editor at that moment is Roger Coleman, who is steering the magazine towards American mass culture and a cutting-edge technophile attitude to graphic design; Coleman is then recruited to Lawrence Alloway’s exhibitions committee at the ICA; Alloway puts together Coleman’s painting schoolmates Robyn Denny and Richard Smith with Guy Debord’s London acolyte Ralph Rumney, resulting in the 1959 show Place, which, with its immersive installation of paintings ostensibly responding to American largescale abstraction, suggests a quite different attitude to visual sensation plugged into the reality of mass media, and by implication, a new sensibility to the city and urban culture.

This new sense of the mobile, self-making individual, alert to commodity culture and media, is the ‘Mod’ Crow seeks out in his parallel tales of artistic emergence, siting the familiar alongside the less well-known; David Hockney’s explosive early success framed in relation to his less-feted contemporary Billy Apple; the shortlived Pauline Boty’s Pop painting alongside the enduring Bridget Riley’s Op. In each, Crow points out the fading exclusivity and hermeticism of high (and male and heterosexual) modernism giving way to the heterogenous and horizontal interdependencies of ‘Mod’. But the Mod sensibility is soon to dissolve in the endpoint of individual self-affirmation – hippydom and the counterculture, which Crow treats in the final two chapters.

Underpinning Crow’s kaleidoscopic enthusiasm for British culture at a moment of extraordinary fertility is, it turns out, a long-range dispute with the disciplines of the New Art history and cultural studies. Crow’s Mod is, in essence, a cousin of the denizen of Paris in the nineteenth century (on which Crow cut his art-historical teeth) and he bookends his chapters with criticism of T.J. Clark (a key figure of the New Art History) and cultural studies, seeing in their theorising of the spectacle of Parisian modernity and of contemporary youth subcultures a parallel condescension of the ‘petit-bourgeois’ subject – that is, not politically radical or ‘authentically’ working class, but an individualist hopelessly adrift in the capitalist spectacle. Crow is no revolutionary, but it’s the self-conscious ‘modernist’ awareness of that spectacle, and the claim of working-class and subaltern agency that stems from it, that The Hidden Mod is determined to defend.

The Hidden Mod in Modern Art: London 1957–69, by Thomas Crow, published by Paul Mellon Centre