In foregrounding the work of young artists, this edition takes on a tenacious, quietly stirring tone

This thoughtfully curated Whitney Biennial features the work of 63 artists, the majority relatively young, whose works prod the fragility of the American Dream through the prism of civil-rights struggles, racial violence, mass incarceration and environmental destruction.

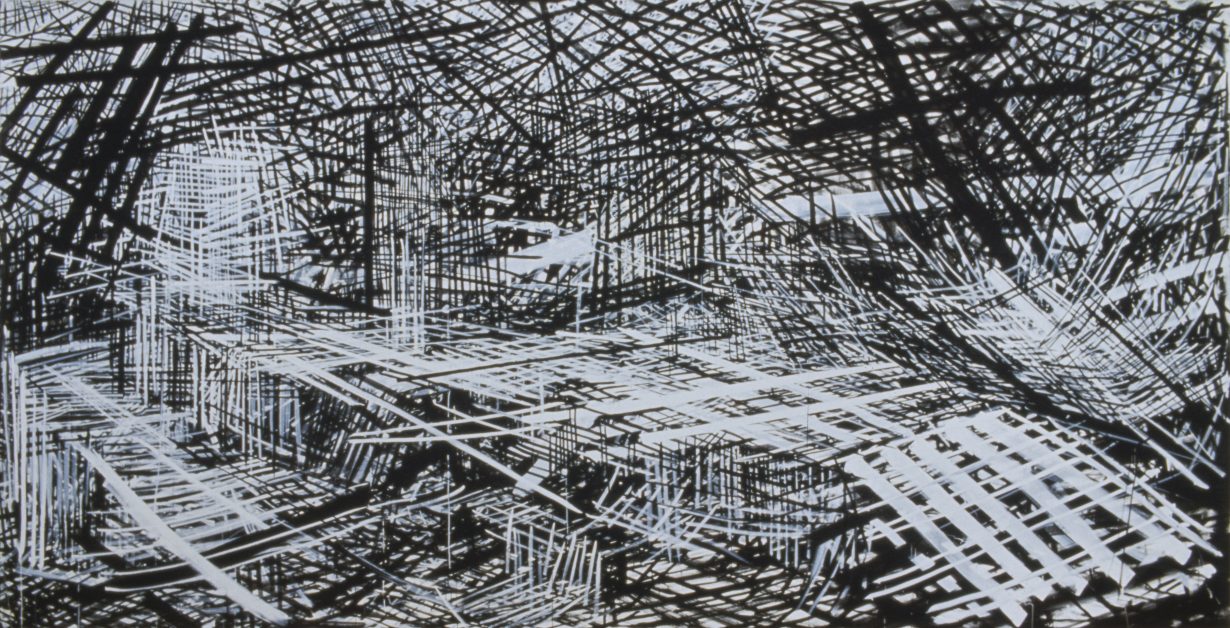

On the top floor of the museum, which is painted and carpeted in black, Denyse Thomasos’s obsessively layered, glorious black-and-white abstract acrylic painting Jail (1993) – corresponding, according to the wall text, to a prison at a colonial slaving depot – is paired alongside the similarly vigorous Displaced Burial/Burial at Gorée (1993), referring to a burial ground on Gorée Island, Senegal.

Thomasos was featured, alongside Ed Clark and Stanley Whitney, in a 2002 exhibition titled Quiet as it’s kept (in turn referencing uses of the phrase by Max Roach and Toni Morrison), a show the biennial’s curators state was a paradigm for how to think about identity in porous ways. This last intent is convincingly conveyed by the biennial itself, with many works as attentive to formal as to social content, rendering them more open-ended. It’s true of Thomasos’s diptych, whose imposing, distorted grids are intensely claustrophobic – suggesting the oppressiveness of colonial systems – and yet, when looked at more closely, seem also to suggest a great degree of freedom, conveyed by the sheer multidirectional sweep and fugacity of lines.

In the exhibition materials, the Black American painter James Little, who grew up in the segregated South, also speaks of abstraction as an expression of freedom. In Little’s resolutely controlled series of paintings, Exceptional Blacks (2021), a mixture of oil and wax produces a unique, mercurial colour, shifting from opaque, inky black to metallic ash. A similarly protean quality emanates from the work of Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore. In her sculpture ishkode (fire) (2021), a sleeping bag, cast in rust-coloured clay, evokes a spectral figure – the bag’s blackened folds rising from a mound of shimmery bullet casings.

Several video-works convey a lyrical intensity. Coco Fusco filmed Your Eyes Will Be an Empty Word (2021) while boating around Hart Island, in the Bronx, site of the US’s largest paupers’ grave through numerous pandemics. Poet Pamela Seed provides a voiceover performing Fusco’s passionate reflection on the statistics of illness and burial, alienating epidemiological vocabulary (“contagion”, “isolation”), human vulnerability, fear, but also resilience, in the face of death.

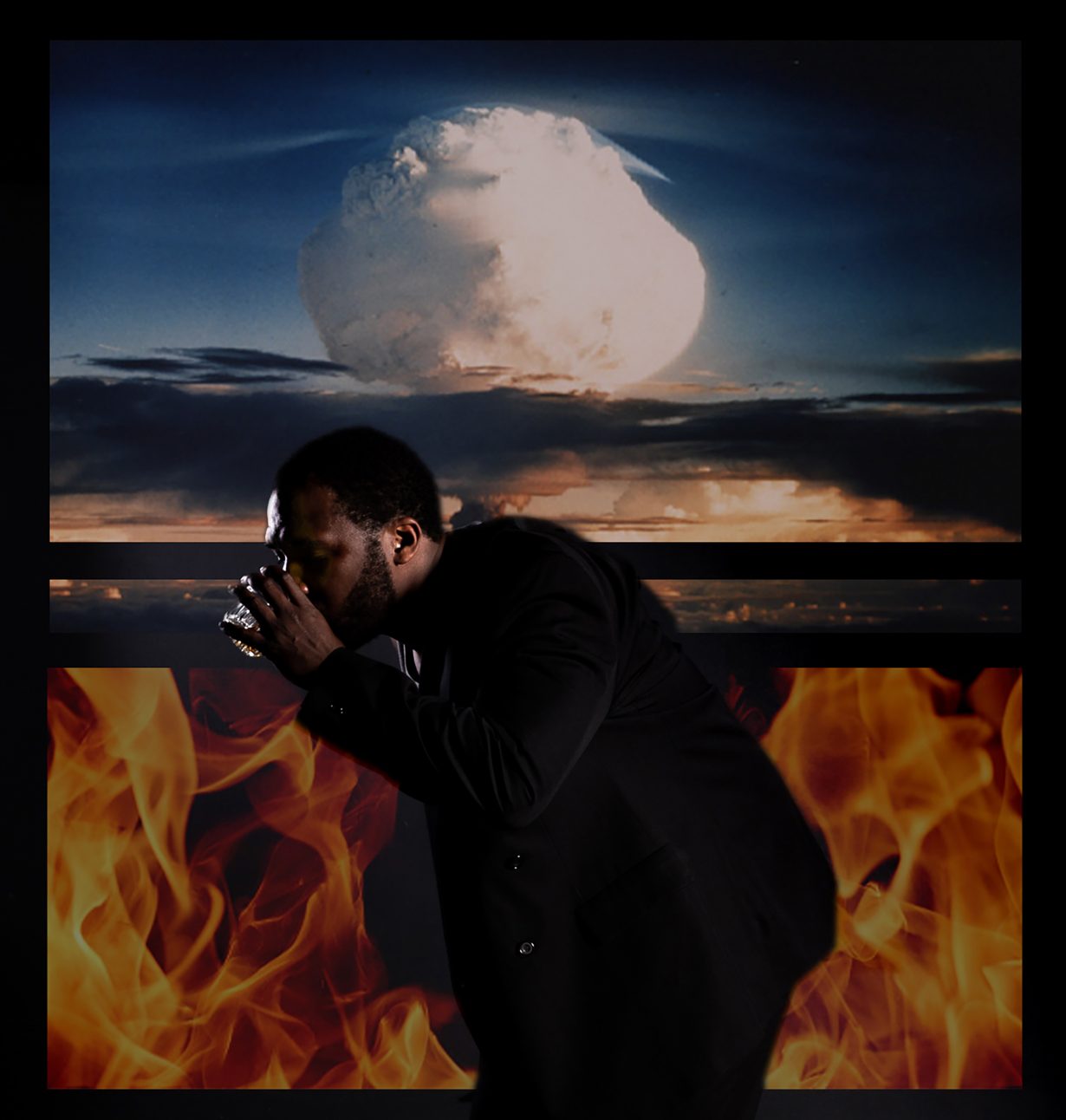

Kandis Williams presents a four-channel video installation, Death of A (2021), in which monologues from Arthur Miller’s 1949 play, Death of a Salesman, and words by Albert Einstein and others are delivered by a Black performer shown across two screens, while the other two screens show clips of Black men portrayed on television and in cinema in wartime settings. Williams’s installation is a rhapsodic investigation of masculinity bound up in the politics and economics of power, and of familial love. Similarly to Thomasos and Little, but also to several younger artists, such as Woody De Othello, Danielle Dean and Na Mira, Williams engages the past to address the present from a personal perspective.

On the fifth floor, which is brighter, with an open floorplan, videos by the Korean-American conceptual artist and writer Theresa Hak Kyung Cha are shown behind a gauzy curtain. Kyung Cha’s scrambled words – such as in the video displaying a white T-shirt that reads ‘A MARR CAN ISM’ or photographs documenting her ‘A BLE W AIL’ performance – speak to an expansionist notion of borders, with signs ‘smuggled’ across cognitive roadblocks. An equally playful albeit nonverbal approach informs Emily Baker’s pet-plastic Kitchen (2019), a group of see-through cabinets, some hung unusually high, commenting on her experience of using a wheelchair. Here transparency (and inclusion) is a mirage, evidenced by a pointed displacement. And like Kyung Cha’s performances, Baker’s installation makes the human body art’s anchor, and ultimate measure. As do De Othello’s earthy-toned ceramic sculptures of domestic objects, some morphed with human body parts, to sensuous effects. The maze-like, obdurately expansionist brushstrokes in artist and community-organiser Rick Lowe’s acrylic painting Row Houses: Artists Are Creative, So Why Can’t They Provide Solutions (2021) embody the fallibility that art shares with the sciences, and encapsulate the tenacious, prodding, quietly stirring tone set by the curators of this biennial.

Quiet As It’s Kept at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York through 5 September