A focus on the country’s sociopolitical fissures grounds this ambitious yet occasionally sweeping survey of its art and architecture in time and space

Manzar is an Urdu and Arabic word meaning perspective, view or landscape, but it is a sonorous recitation in Farsi that beckons us to the recessed entrance of this exhibition. The sound is part of Ali Kazim’s The Conference of Birds (2019), an interpretation of Farid-ud-Din Attar’s twelfth-century metaphorical voyage of self-discovery. In the context of a national survey exhibition, Kazim’s exquisitely rendered depiction of a flock of birds in various stages of flight suggests the search for a unified national vision. The work’s juxtaposition with Zones of Dreams (1996) – Salima Hashmi’s sensitively painted monumental map of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh – however, opens up alternative readings of migration and displacement associated with the 1947 Partition of the British-ruled India and the creation of Pakistan. In an inadvertent continuation of the avian theme, Pakistan, created as a home for South Asia’s linguistically and ethnically diverse Muslims, was initially realised with two wings separated by the vast expanse of India in between. This geographically unlikely arrangement collapsed with the bloody 1971 liberation war, in which the Bengali language movement played a critical part, after which East Pakistan became Bangladesh.

Kazim’s and Hashmi’s works are selective interruptions to a broadly chronological 80-year survey of Pakistan’s art and architecture. This vast exhibition features more than 200 works by over 60 artists and 15 architects, arranged in 13 sections in the National Museum’s gallery spaces, with additional works dotted around the museum’s courtyard. The whole locates us in time and place, presenting broad movements in visual expression (including calligraphy, contemporary miniature, vernacular pop), and revealing the conceptual debates and sociopolitical fissures with which they are entangled. Manzar’s displays are punctuated by carefully assembled vitrines of archival material – from radio broadcasts and newspaper clippings to photographs, publications and ephemera from exhibitions as well as social marches – to offer a contextual foundation to audiences for whom the names, objects and history may all be unfamiliar. The exhibition breaks new ground in putting forward one of the first instances of Pakistan’s architectural history being shown alongside its better-rehearsed art history.

Anchored in primary research, and buttressed by plans, models and insightful interviews, Manzar reveals the competing demands of ‘heritage’, ‘regionalism’, ‘development’ and ‘environment’ that have shaped architectural thinking in building the nation over the last eight decades. Nayyar Ali Dada, Habib Fida Ali, Kamil Khan Mumtaz, Arif Hasan and Yasmeen Lari present a culturally sensitive, polyvocal riposte to an earlier generation of international modernist architects (among them Constantinos A. Doxiadis, Louis Kahn and Richard Neutra) commissioned to shape cities and civic buildings across a newly created Pakistan.

A specially commissioned series of bamboo, mud and plaster structures in the courtyard offers a 1:1 encounter with Yasmeen Lari’s groundbreaking architecture ‘for and by the poor’. Lari’s zero-carbon shelters for those impacted by Pakistan’s devastating earthquakes and floods have won her international architecture prizes and were also featured in the 2024 Lahore Biennale. Here, their organic minimalism presents a productive contrast to the steel and glass of Doha’s skyscape, and formally extends the handmade, ludic challenge of Rasheed Araeen’s wooden lattice-structures (such as 4rS, 1970–2016; shown in the ‘New Languages’ section of the exhibition) to the industrial austerity of capital ‘M’ Minimalism. Two of Lari’s structures host Karachi LaJamia’s playful pedagogic installation Hamare Siyal Rishte (Our Watery Relations, 2021–24) and Noorjehan Bilgrami’s newly commissioned textile installation, Nir Kahani – Indigo Story (2024). This braiding together of artistic and architectural strands is a welcome exception in the exhibition, where the two disciplines maintain a respectful distance, like strangers in a lift. This is puzzling when a number of contemporary artists including Bani Abidi, Noor Ali Chagani, Seema Nusrat and Rashid Rana have experimented with myriad forms that straddle the two.

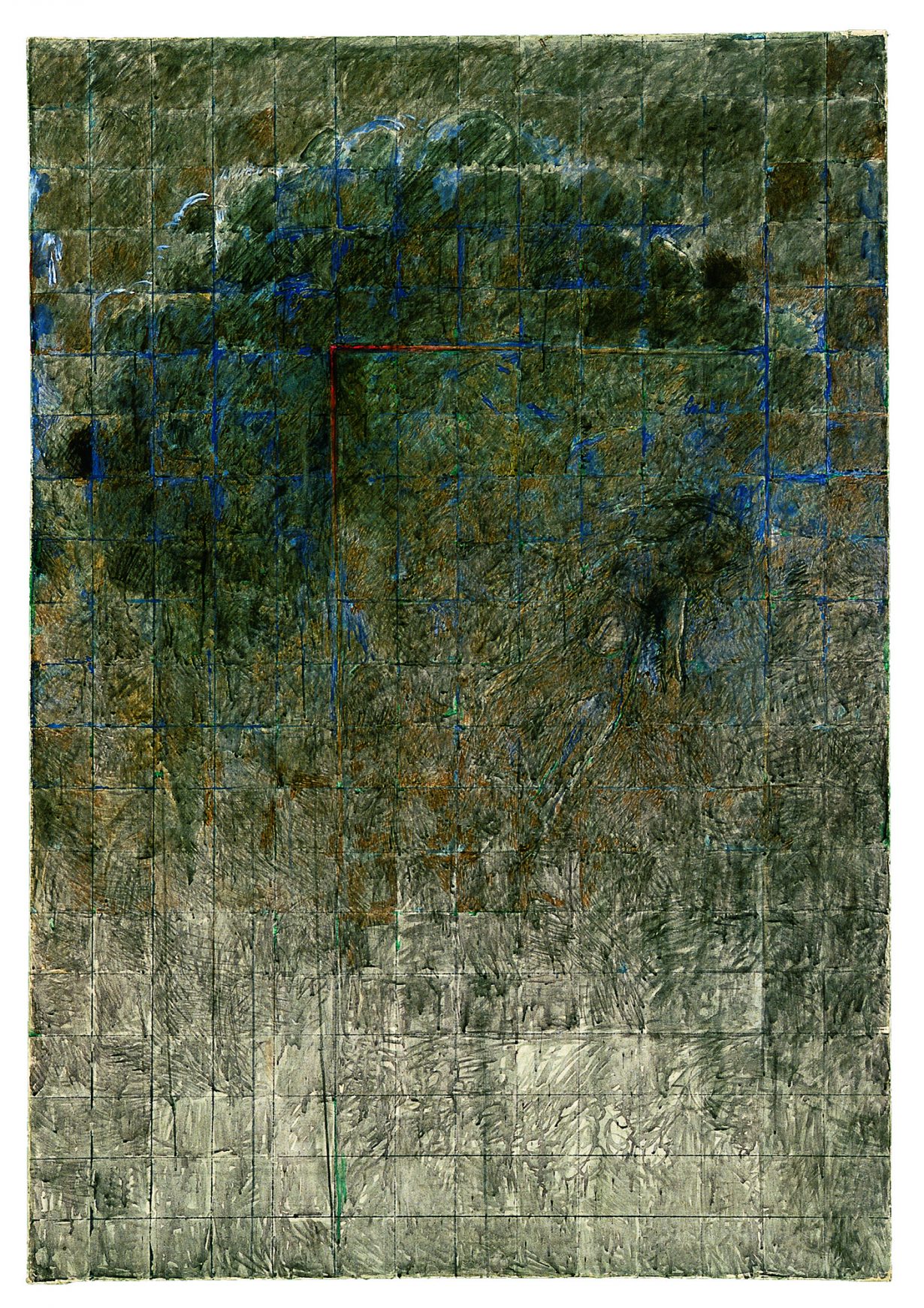

While the architectural history is innovative and propositional, the art strand in Manzar builds on a number of influential exhibitions and publications in Pakistan and abroad. It assembles the work of Pakistan’s modernist pioneers, including Zubeida Agha, Shakir Ali, Sadequain and Anwar Jalal Shemza; internationally renowned contemporary artists of Pakistani heritage, including Hamra Abbas, Huma Bhabha, Aisha Khalid, Imran Qureshi, Shahzia Sikander and Salman Toor; and a generation of influential artists, writers and teachers who bridge the two, including Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Lala Rukh. The visual dialogue between Sadequain’s jagged cactus-inspired shapes (for example, in Resurrection, 1963) and Akhlaq’s exploration of the grid as an arrangement of space and form in paintings (View from the Tropic of Illegitimate Reality, 1975–78), sculpture (a striking arrangement of 15 polished-steel pyramids, Untitled, c. 1975) and public monuments is a particular highlight.

Another highpoint is Mariah Lookman’s mesmerising film commission Behrupiya (Mimic, 2024). The moving image – all orange tints, scratches and dark shadows – is the damaged remains of a documentary on Sadequain handed to the artist in 2016 in an 8mm-film tin. In an act of material and cultural repair, Lookman has collaborated with the novelist H.M. Naqvi to step into the gaps of the archive with a scripted conversation between the missing subject, Sadequain (through his verse), and the writings of his foremost critic, the late Akbar Naqvi.

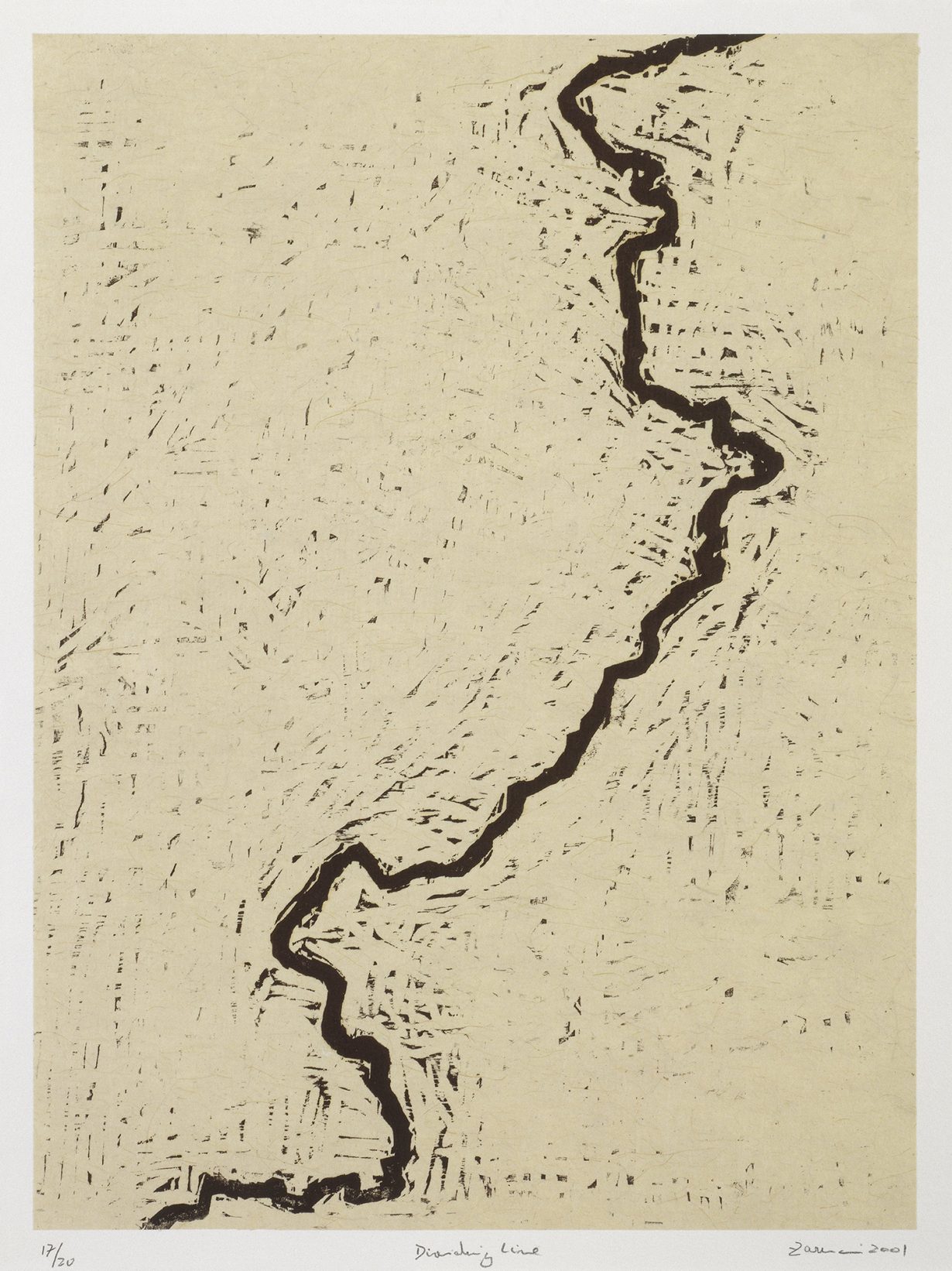

Zarina is among a handful of non-Pakistani artists included in the exhibition in order to acknowledge their impact on art practices and institutions within the country. Her extraordinary prints (including Dividing Line, 2001) are shown alongside David Alesworth’s Lawrence Gardens (Bagh-e-Jinnah) (2014) – a colourful antique Kashan carpet bearing an embroidered line-map of colonial-era Lahore’s Lawrence Gardens, which itself was modelled on London’s Kew Gardens. These works, of contrasting scales and aesthetic registers, are among the exhibition’s most fruitful juxtapositions, acting as palimpsests of private memories and public histories.

Manzar contains many brilliant individual flourishes as it puts forward an art history attentive to the social and institutional contexts in which it is embedded. But this art history is also a somewhat eccentric one. Many artists are represented by works of uneven quality, perhaps the result of an overreliance on a small number of collections; while an understandable desire to give prominence to works in the collection of Qatar’s Art Mill Museum (currently projected to open in 2030) means space is not always used to the works’ best advantage. Several largescale works by Aisha Khalid, Imran Qureshi, Khadim Ali and Rashid Rana jostle for attention for instance. And while three rooms are allocated to a new commission by Omer Wasim, entire artforms important in Pakistan’s art ecology (ceramics and printmaking) are excluded; as are far too many art-historically significant artists, including Ijaz ul Hasan, Khalid Iqbal, Bashir Mirza, Mussarat Mirza, Nagori and Jamil Naqsh.

Manzar has, however, set a stage on which new perspectives might emerge. Ensconced within the umbrella of Qatar Museum’s wider programme (Manzar opened alongside exhibitions exploring the work of French Orientalist painter Jean-Léon Gérôme and a retrospective of the American artist Ellsworth Kelly), it will undoubtedly introduce new audiences to the vital art and architecture of Pakistan – not least the nearly 300,000 Pakistani residents of Qatar; a number approaching the population of Qatari citizens and one set to grow following the announcement of intergovernmental labour initiatives earlier this year.

MANZAR: Art and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today at National Museum of Qatar, Doha, through 31 January

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.