Celine Song’s follow up to Past Lives compares finding love under hyper-capitalism to working at a morgue

In Materialists, the writer-director Celine Song attempts to marry two genres together into one harmonious riff on the rom-com: a nihilistic, hetero-pessimist satire, and a circa-2020s reimagining of the comedy of remarriage, in which love conquers all. What results is a union that intrigues, but seems fated to end in divorce. At the centre of the film is a triangle revolving around Lucy (Dakota Johnson), a New York matchmaker who earns a relatively modest wage, but inexplicably looks like a person made of money. Her admirers are John (Chris Evans), a cater waiter in a flat share who wants to be an actor, and who even more inexplicably looks like a person made of money, and Harry, a dashing older bachelor whose own luxe looks are explained by the fact he is an-ultra rich financier, and also by the fact he has the rare good fortune of being played by Pedro Pascal. Lucy is a genius at her job, and her genius in the matchmaking field has turned her into a loser when it comes to the age-old game of romance: she is incapable of seeing other people as anything more complex than a series of statistics – height, weight, wealth, age, and so on – and she cannot stop using the word “math” in conversations about love. (By my reckoning, she uses it six or seven times in this context, although unlike Lucy, I admit that I am not really one for arithmetic.) Once, Lucy was with John, but the two of them broke up over the disappointing size of his bank balance. Now, she is waiting to find someone rich enough, and tall enough, to be her husband. “Marriage,” she says primly, “is a business deal. And it always has been, since the very first time two people did it.”

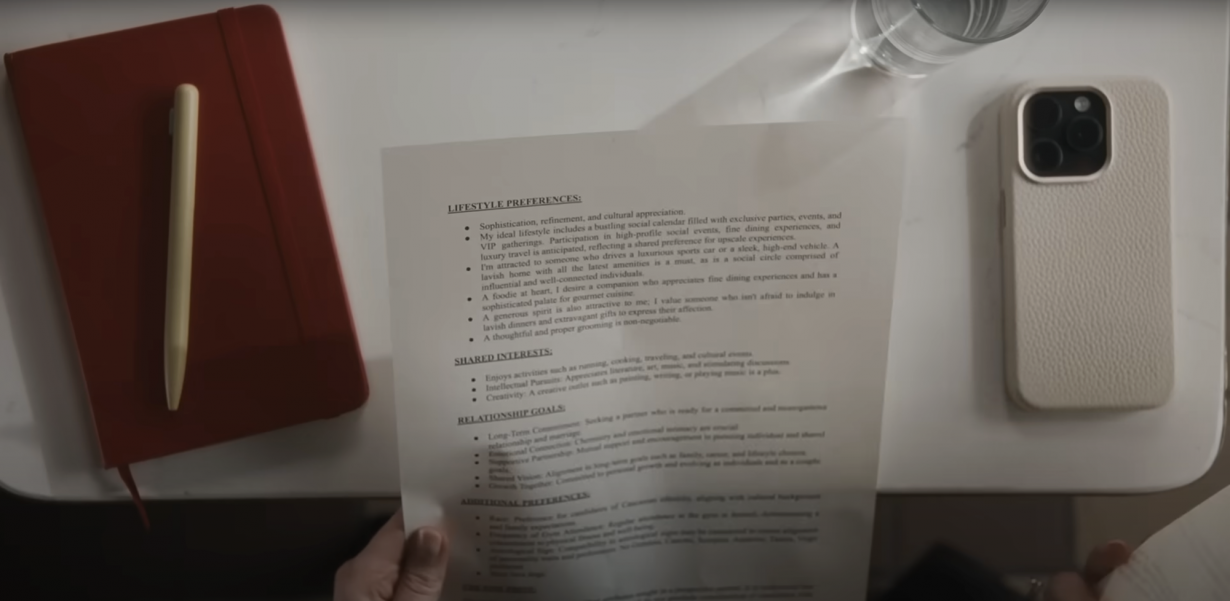

All this means that rather than being a typical – thus typically appealing – rom-com lead, Lucy is a kind of hyper-capitalist antiheroine, in pursuit of a white knight from Wall Street: one, ideally, with a great big lance and a very heavy wallet. In the meantime, she is pouring her efforts into finding the right partner for a long list of affluent single men and women, and the scenes of her interviews with clients offer us both the great pleasure of seeing an unusually competent professional excel at her job, and the horror of discovering what happens when people are encouraged to view prospective suitors as optimised products. What is the difference between men and women? To paraphrase that old, perhaps-apocryphal Margaret Atwood quote: men are afraid that women will be fat or over twenty-five years old, and women are afraid that men will be poor, or too short, or have no hair. Such is the view of contemporary dating put forward in Materialists, and I found the abject nastiness of many of these brief conversations truly bracing, like dunking my head in an ice-cold bucket of Dom Perignon. Song herself once worked in the field, and one has to assume that these moments have a ring of truth about them. Has Lucy helped to make the singles that she represents this unfeeling, or has she simply hardened herself to meet the merciless demands of a preexisting market? Consider the scene where she is called in to comfort a bride on the morning of her wedding. “Why do you really, in the darkest, ugliest part of yourself, want to marry Peter?” Lucy asks. “He makes my sister jealous,” sniffs the bride. “This is about value,” Lucy offers, in the calm and measured voice of an operating system. “Peter makes you feel valuable.” It is a soft gloss on yet another horrible preference, and its phrasing is plausibly suggestive of both therapeutic language and financial terminology. The bride is convinced, and the marriage goes ahead.

Being a matchmaker is similar to “working at the morgue”, Lucy tells Harry the first time they meet. The analogy is pleasingly gothic, and also fairly accurate: the beating of the heart and the flutter of the pulse are of very little interest to Lucy, who cannot meet a person without stretching them out on the slab in her mind for inspection and assessment. This image of her as a master mortician is invoked once again when she and Harry finally go on a date, and Song shows them making airless, inert conversation with each other, full of strange phantom pauses and devoid of discernible emotion. “How am I as a corpse?” Harry asks. “A good corpse,” Lucy nods in response. The fact they end up fucking at the end of such a lifeless and unerotic evening is surprising; then again, since the sex happens offscreen, we’ve no idea if it’s actually hot. (One can’t help but picture, once again, the barely-animate bumping together of two bodies in a mortuary freezer.) It is heavily implied that Lucy’s lust is not for Harry, but for Harry’s palatial apartment, the elegant restaurants he dines in, and his status as what she calls a “unicorn”: a rich, single man over six feet tall. It took three generations of Hollywood royalty to produce Dakota Johnson, a louche and terrifically charismatic beauty with a wicked sense of humour. Pascal, likewise, is as famous for being funny and charming as he is for his looks. With this in mind, placing these actors together as lovers and producing a dynamic as frigid as this must, presumably, take far more work than simply sitting back and letting them bounce off each other. One assumes, therefore, that the relationship is dead by design. This is bad chemistry as social commentary, a gambit that works well enough while Materialists still appears to be a tragicomedy about theruinouseffects of capitalism on romance – not a new theme in cinema, exactly, but one that might feasibly produce fresh results when effectively filtered through the lens of the rom-com: a genre whose high-gloss style begs for a touch of enlivening malice.

More troublesome is Song’s eventual pairing of Lucy with John for what seems to be a classic happily-ever-after ending. Harry may tick all of Lucy’s boxes, but penniless John, with his passion for theatre and his architecturally significant jawline, is the one who can assure her he’ll still love her with grey hair and with lines on her face. It is a sweet enough sentiment. For most of its runtime, however, Materialists is not a sweet film – its very sourness, in fact, is its most subversive quality. Accordingly, this sudden volte face makes John and Lucy’s tenderness feel misplaced and naïve. Opting for swooning romance in the year of our Lord 2025 takes guts, and it also requires a degree of willful blindness: to the cruelty of contemporary dating, to the still-extant social and cultural inequalities between men and women, and to the pressure that the need for financial solvency can place on even the happiest marriages. Prior to Lucy and John’s reconnection, Song has spent scene after scene forcing our eyes open as if she were subjecting us to the Ludovico Technique, making it difficult for us to attain the required state of ignorant bliss to enjoy the gentle montage of city hall weddings that runs under the credits. I believe that I understand her personal predicament: she is, just as I am, a furious, feminist cynic who still believes in love. Such a contradiction is hard to negotiate in life, and it is also hard to negotiate on film. By the time we have been asked to rush breathlessly past a tossed-off subplot about rape so that the film can devote more attention to Lucy and John’s rekindled relationship, the balancing equation of Materialists’ tone is absolutely, as the kids say, not mathing, and even Lucy getting out her mental calculator for the seventh or eighth time won’t move the needle.

That Materialists opens with a vignette of two cavepeople courting before cutting to present day New York seems, at first, like a gag about love being as old as human history. When John, in the very final scene of the film, is shown proposing to Lucy, he does it in exactly the same fashion as the caveman from the start: by tying a daisy, like a single-flower chain, into a ring on her finger. “Would you like to make a terrible financial decision?” he asks her, and her answer is yes. (Lucy has, thank God, just been promoted, and this raise ex machina helps to solve the issue of John’s apparent poverty.) Later, I found myself wondering whether Song, in repeating that gesture with the daisy, really was suggesting that love was eternal, or whether she was actually saying that marriage is a primitive affair. I sat down to write this thinking that I disliked Materialists, and yet the more I thought about it, the more that I found to grab onto. It’s a failure, but an interesting one, and perhaps part of the reason it feels like a failureto me personally stems from the fact that in my own balance of cynicism and romanticism, it is cynicism that tends to win out. Ultimately, what those amorous Neanderthals reminded me of was a scene from another tonally ambitious rom-com, the beloved HBO series Sex and the City, in which our love-obsessed antiheroine Carrie is encouraged to start therapy after splitting from a dashing financier. “Ancient man didn’t need shrinks to survive,” she protests, shrugging off the suggestion. “Ancient man,” her pragmatic friend Miranda snaps back, “only lived ‘til 30.”

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norfolk. Her latest book is It’s Terrible the Things I Have to Do to Be Me (2025)