Where do revolutions happen nowadays? In the streets, is the most immediate answer; on Tahrir Square, in Zuccotti Park and most recently in Maidan Square too. But just as often they happen behind closed doors, far away from the visibility of outdoor public space and the supposed transparency of democratic decisionmaking. In fact, some of the most profound revolutions take place in locations where iPhones are switched off and TV cameras are absent: at board meetings and on the desks of bureaucrats.

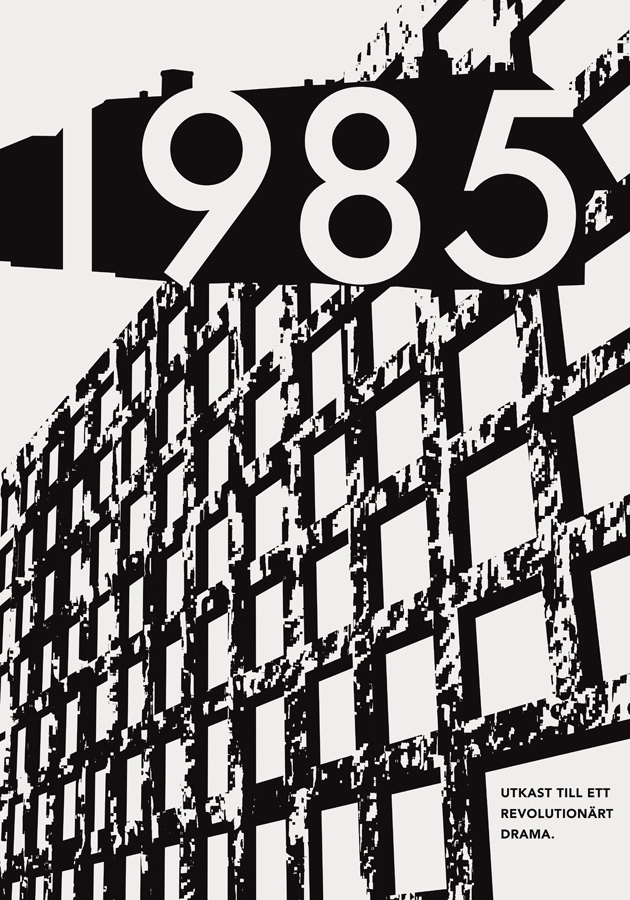

A revolutionary plan, which changed the course of both economics and politics in Sweden, was shaped on 21 November 1985 in a villa in the countryside near Stockholm. The board of the Central Bank of Sweden met there to come to terms with the weakening economy, decreasing profits for industry and increasing unemployment. Their solution was to make the banking sector autonomous by deregulating the credit market, an initiative endorsed by Olof Palme’s Social Democratic government at the time. This unspectacular, and largely unknown – albeit certainly revolutionary – event is the object of artist Andjeas Ejiksson’s work 1985 (2011). The work takes the form of a play featuring the characters who attended the board meeting, conceived for the villa itself and its surrounding picturesque landscape. It was commissioned by Lisa Rosendahl, director of the International Artists Studio Program in Sweden (Iaspis), itself part of the state authority Arts Grants Committee, which answers directly to the Ministry of Culture.

Power has moved from the representatives of parliamentary democracy to public and private bureaucrats

That the influence of bureaucracies has been growing rapidly since the advent of ‘new public management’ in Western Europe is palpable in most sectors of society, whether the influence is revolutionary or not. Power has moved from the representatives of parliamentary democracy to public and private bureaucrats. A prominent feature in this process is the ubiquity and impressive volume of assessments and controls of different kinds. We count, weigh and measure more or less everything, and evaluate the results. The protocols for doing so go by various names: reviewing, inspection, certification, revision and quality control are some of them. The field of contemporary art is as affected by this as much as anything else; it is palpable in both artworks and their subjects, and how organisations operate. But in contrast to Benjamin Buchloh’s, ‘aesthetics of administration’, it has more to do with methodology, protocols and rituals than visual aesthetics – it has to do with the performance of bureaucracy.

But why do we review and assess so much? And what are the consequences? One explanation is that the public sector over the last 20 years has gone through a process of ‘organisation making’ – ie, agencies and other entities have striven to become ‘proper’ organisations. For this to work effectively, they need – understandably – to be definable, measurable and manageable, characteristics derived from steering mechanisms used in business management. In addition to this there has been a tendency to decentralise, which has led to responsibility moving downwards in the hierarchies.

In order to make sure that this freedom is not used in the wrong way and that disorder does not occur, reviews and assessments are useful. But this is a prescriptive use: the assumption is that without the inspections and assessments, problems might occur, so one needs to perform the inspecting and assessing as a core activity. And as we know, reviews and assessments often lead to a demand for more – and presumably better – reviews and assessments. Ultimately they are used as an instrument of control – to make people do what you want them to do.

Whereas politicians hang on to the idea that reviews and assessments signal action and engagement, they are in reality replacing political responsibility

When this logic of assessment starts to dominate other logics (for example, professional logics specific to each field of activity), an ‘imaginary rationality’ comes about. Especially when the reviewers and assessors can implement sanctions. Furthermore, as these figures rarely delve into the activities they are examining themselves, they have to rely on reports, which in turn makes the bureaucracy grow, stimulating rituals of control. However, reviews and assessments are often made too narrowly and any new knowledge they might produce doesn’t enter the relevant arenas – at the end of the day, change in organisations happens through established power relations and ideology, not through reviews and assessments. Whereas politicians hang on to the idea that reviews and assessments signal action and engagement, they are in reality replacing political responsibility.

For Ejiksson, this – how bureaucracies become sites of condensed influence and executive power, a force to be reckoned with – is fertile ground. However, 1985 still waits to be staged. The Arts Grants Committee, through a high-ranking bureaucrat, in 2013 suddenly erased the play from the agenda of art projects by Iaspis that had to be approved by the board. This makes the context of the commissioning of the play, via a state agency that has gone from being, during the 1990s, one of the most vivid and artist-centric platforms in Europe to now being ruled by the bureaucracy, even more interesting. In all its banality. Iaspis also happens to be the place where, during my tenure there, the word ‘bureaucracy’ was banned from official use – as Foucault already taught us: real power always tries to conceal itself.

This article was first published in the May 2014 issue.