In its twelfth iteration, the Sharjah Biennial – an exhibition that in the past distinguished itself for ambitious projects developed in situ, a focus on art and performance in the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, and inclusions that incisively explored migration, secularism and radical faith, among other dynamics critical in the region and the greater ‘international’ beyond it – eschews critique and politically trenchant content to consider how art might signal what is ‘possible’ in today’s world. Inherently pragmatic, though not devoid of idealism, the concept seems to complement an idea the show’s curator, Eungie Joo, first mooted in The Ungovernables, the 2012 triennial she organised at the New Museum in New York: that in art, as in nonviolent political resistance, disobedience and withdrawal can both circumvent existing power and engender new artistic and social structures.

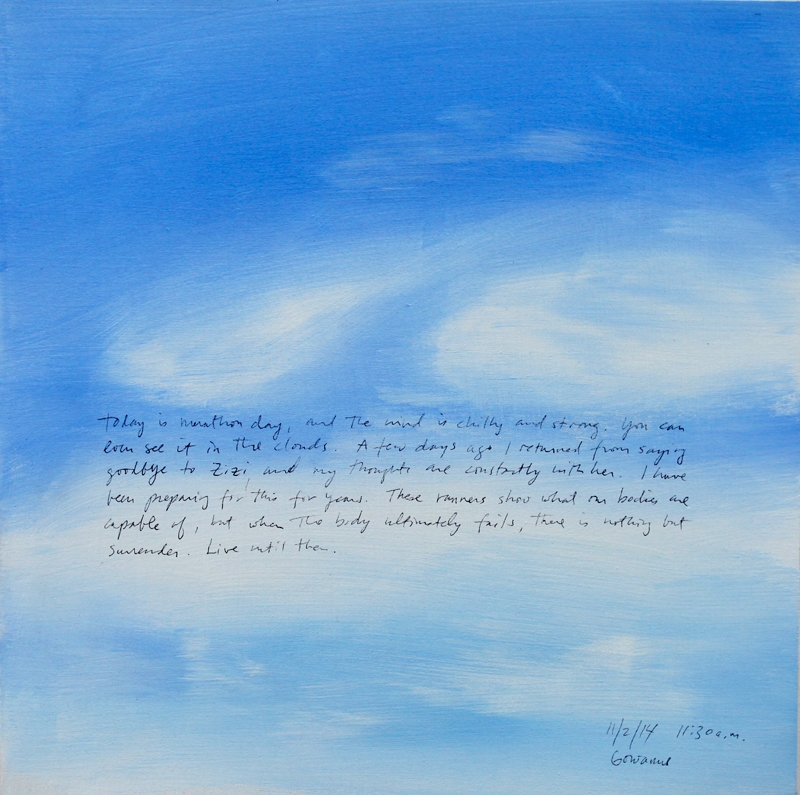

What these ‘possibles’ might be remains unclear. Rather Joo’s concern here is with how artists look at the past and present in ways that might allow us to imagine the future afresh. Experience is the unifying thread. Sensation and physicality, interpretation and emotion, are its constituents and are also the raison d’être of much that’s on view. Byron Kim’s Sunday Paintings (2001–), an ongoing series depicting the sky on which Kim inscribes various musings, construct an intimacy of specific detail and, in their combination of random reflections and references to current events, suggest ways in which the private and the public intersect. A selection of work from the 1980s by the Emirati conceptualist Hassan Sharif, including a table with a wool-covered bottom that visitors are invited to feel, proposes individual investigation and scepticism as requisites of engaged viewing and, by extension, living. They also signal that Modernism is more than a phenomenon of the Atlantic world, and that Conceptualism can be sensuous and multivalent, not just heady, though neither point counts as news.

Joo’s concern here is with how artists look at the past and present in ways that might allow us to imagine the future afresh. Experience is the unifying thread. Sensation and physicality, interpretation and emotion, are its constituents

Sharif’s pieces anchor a long sequence of galleries in the Sharjah Art Museum, one of the few venues in which work by more than two or three artists is installed together. This includes a small survey of the Lebanese master Saloua Raouda Choucair, born 1916, whose abstract sculpture incorporates elements of Arabic calligraphy and reflects an interest in Sufism. The display ends with a selection of plaster reliefs from the 1970s and 80s by Abdul Hay Mosallam Zarara. Painted in garish colours, they alternately depict scenes from Palestinian life, weddings, Iftar feasts and suchlike, and Surrealist amalgams of martyrs and monsters, including a golemlike figure inscribed ‘Pinochet’. Together they assert that for Palestinians daily existence itself constitutes resistance.

If Joo intended these juxtapositions as a statement about the complex links between the personal, the political and the social, the inclusion here of Byron Kim’s work – which is more introspective than visionary – or Beom Kim’s neo-Dada plays on canvas as surface (a painting cut to resemble bricks, for example) reduces the mix to a superficial, muddled exploration of how experience is represented in art.

An introductory wall text nearby refers to the need ‘for wonder, mindfulness and query at this particularly disharmonious and decadent moment in history’. Past biennials have deftly explored such implied urgencies and their immediate effects as, for example, the years-long engagement between the Indian collective CAMP and the crews on the dhows that dock in Sharjah and trade between Gujarat, the Emirates and Somalia. This collaboration resulted in a ship-based pirate radio station that broadcast during the 2009 exhibition and a film with content generated by sailors screened during the 2013 version. Both projects pioneered new dynamics of artistic inclusion while parsing economies of trade, movement and political isolation.

This time, much on view seems comparatively anodyne and superficial. Haegue Yang’s An Opaque Wind (2015), an installation of metal partitions, spinning chimney caps that apparently cite Islamic wind towers and local newspapers published for foreign labourers, attempts to gin up references to migration and traditional regional architecture into a poetic play on the titular suggestion of wind. In paintings from her recent Invisible Sun series (2012–15), Julie Mehretu lays skeins of lyrically abstract marks over networks of rectangles in ways that recall Twombly, though her canvases lack his feverdream passion and depth of cultural reference. They are far too large and elegant to convey the ‘emergent potentiality’ or ‘the resistance to participate – [as] a revolutionary act’ the Biennial guide attributes to them.

Rather, as grandiosity yields to solipsism, such work encapsulates – although I doubt intentionally – the pitfalls we all face in inscribing ourselves in a broader polity and underscores how this exhibition fails to cohere into little more than disparate introspections and superficialities.

This article was first published in the May 2015 issue.