An attempt to establish a specific art history of Bangladesh, and to define the role of the artist in that nebulous space

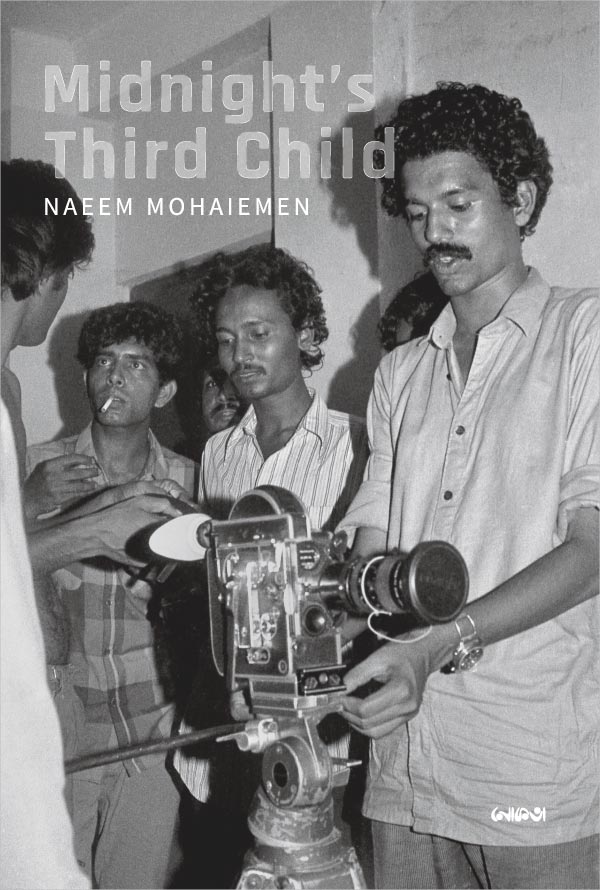

The title of this collection of writing from newspapers, magazines and catalogues by artist Naeem Mohaiemen is a polite translation of a phrase used in Bangla to suggest that the youngest child has to try harder. It refers to Bangladesh, the ‘forgotten’ third child of partition, ‘born’ in its current form following independence from Pakistan in 1971. Much of Mohaiemen’s research as both an artist and a writer is focused around this trinity of states (completed, of course, by the dominant mass of India) and the two moments of partition that created them as they stand today. The effect of all this, the author points out, was as deleterious for the art scene as it was for society in general, with artists choosing between Pakistan, West Bengal (in India, to where many Hindu artists retreated) and Bangladesh (in a reverse flow of Muslim artists). ‘The exact shape of the idea of Bangladesh’, he suggests, ‘remains contingent and contested.’

All this is given a further impetus as his homeland becomes, as he puts it, ‘a laboratory since the 1970s for every major developmentalist theory’ and, not unrelatedly, the latest focus (after its neighbours) of the global artworld’s ‘attention economy’, for both good and bad. (Mohaiemen himself, who was born in London, was shortlisted for the UK’s Turner Prize in 2018.) As a whole, this collection is an effort to establish a specific art history of Bangladesh, and to define the role of the artist in that nebulous space.

In the texts that follow he rails against the limitations of art education; the dominance of English over Bangla (who is the imagined audience?, he asks of local English-language art magazines); and the use of poverty tourism to satisfy white liberal guilt across the Global South. In one text he references the tribal people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (in south-eastern Bangladesh) and Adivasi (indigenous) people more generally, lamenting the fact that the more art is afforded luxury status, the more it loses touch with a general audience. Nevertheless, he points out, the ‘periphery’ – of the Bangladeshi art scene and the global artworld – is precisely the space in which experimentation tends to happen. ‘The work of culture can reinforce essentialist ideas that give succour to hegemonic state mechanisms, or it can choose to challenge majoritarian views, especially vis-à-vis this country’s many others’, is the stark choice he offers in his introduction.

This discussion of audience leads into a text on the country’s advertising industry, which Mohaiemen claims has an audience that art spaces lack and is the natural space in which artists have historically found space for radical(ish) public expression. ‘Forced involvement in national politics is necessarily healthy for local artists,’ he goes on to say, ‘bringing them out of institutional navel-gazing and into larger questions of image-making, ownership and their role as public intellectuals.’ ‘Culture workers’, he declares, ‘were always a significant form of resistance to anti-democratic forces.’ Of which Bangladesh has suffered several.

Midnight’s Third Child is a powerful argument for the notion that, as editor and curator Saida Rahman puts it in a conversation with the author for a 2016 exhibition catalogue, ‘artworks create knowledge’. It’s a powerful tool too for anyone (as ignorant as this reviewer) looking for stepping stones towards the individuals and organisations that make up the still largely veiled histories of contemporary art in Bangladesh, as well as an eloquent argument for the potentials of art in many other territories.

Midnight’s Third Child by Naeem Mohaiemen. Nokta, Rs1,010 (softcover)