An exhibition at the Wellcome Collection delves into the polemics of dairy

The farming of cow’s milk for human consumption, we are told at the outset of this wide-ranging survey comprising art, archival materials and a fairly high-handed interpretational tone, was commercialised in Europe and North America in the early twentieth century before being imposed, in the manner of colonialism, on the rest of the world. (Around two thirds of humanity, mostly nonwhite, are lactose-intolerant.) And while the exhibition includes the odd artefact providing evidence of ancient dairy consumption (for example a Roman terracotta model of a mule laden with cheeses), the exhibition situates itself within contemporary cultural debates.

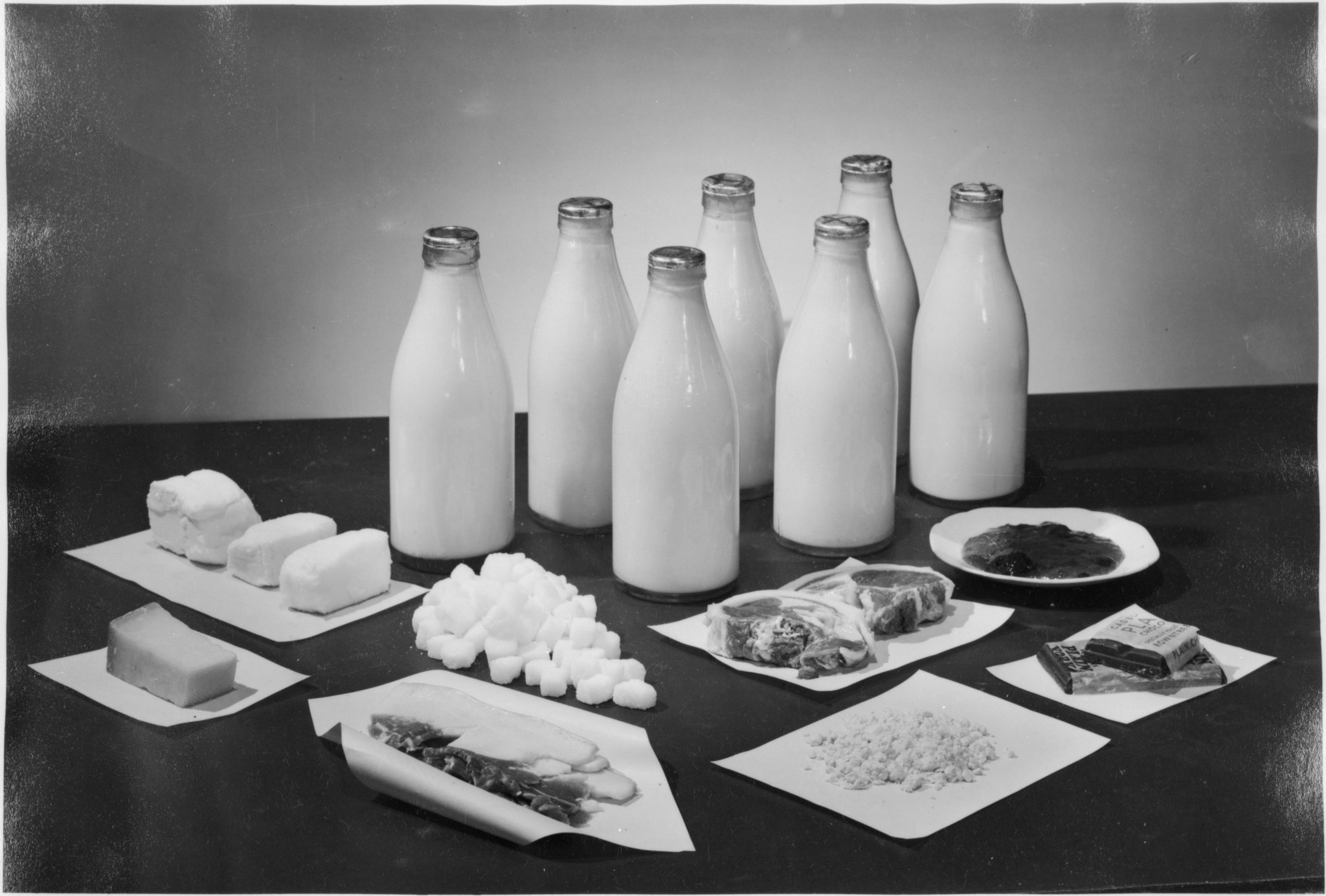

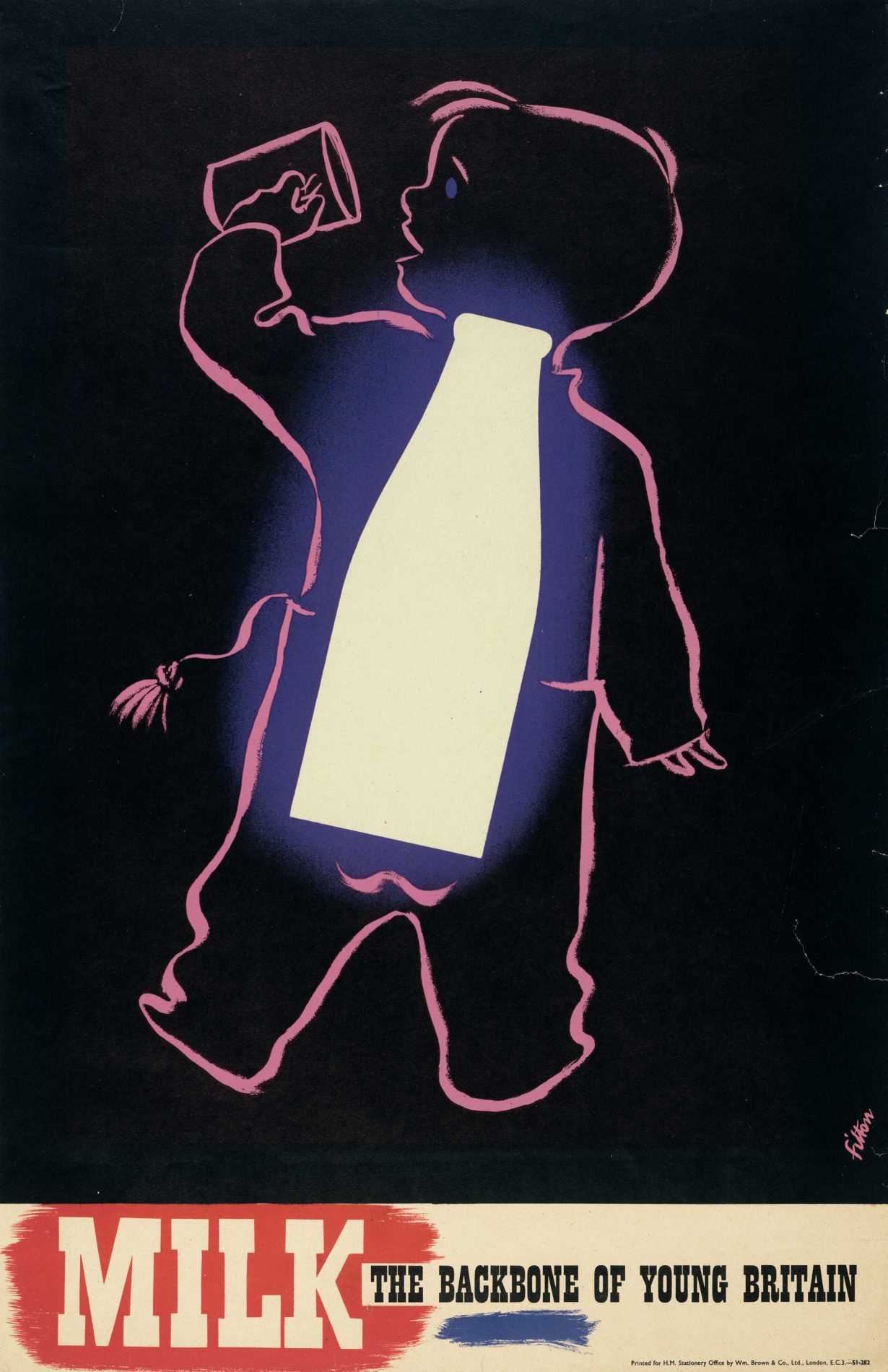

Various nineteenth- and twentieth-century advertisements designed to demonstrate improved hygiene in milk production, with language emphasising the ‘purity’ and ‘cleanliness’ of the end product, feature customers as white as the drink itself and are presented here as race-based dog whistles. In an American dairy producer’s poster from the 1950s – featuring an affluent white Norman Rockwell-style family guzzling the stuff, and tagged with the line, ‘Every member of our family drinks milk’ – the curators note both the apparent aspiration of the image and the exclusionary tone of its slogan. Nor is it just U.S. consumerism under the cosh; the British welfare state gets it too. A photograph of children protesting then-Education Secretary Margaret Thatcher’s planned cuts to free school milk in 1971, a scheme introduced by the Clement Attlee government to improve children’s health in the postwar years, is piously captioned with the claim that many of those students actually ‘resented being forced to drink milk when they did not like it or it made them ill’ (full disclosure: I was class milk monitor aged eight).

The mazelike exhibition moves on to themes of human milk, and here the polemic eases. Debates over breastmilk versus formula are presented with nuance: a 1990s-era hand- printed English-language poster decrying Nestle’s aggressive marketing of baby formula in developing countries is shown alongside British artists Jen Conway and Jessy Young’s 2019 Milk Report project, a booklet detailing the 720 hours Young spent breastfeeding her child. Once 720 copies of the artists’ publication were sold, she was compensated (assuming national minimum wage) for that labour. Shame such a juxtaposition, favouring debate over lecture, was missing elsewhere.

Milk at Wellcome Collection, London, through 10 September