Sami’s paintings at Camden Art Centre, London present a vision of a past on perpetual replay

In Mohammed Sami’s painting Weeping Walls III (2022), a nail pierces a stretch of abstracted floral wallpaper, casting a clock-hand shadow over its drab teal and khaki pattern. While the periphery of the wallpaper appears grimed with time, it frames a paler rectangular area, as though a picture that once hung from the nail has been recently removed. What remains – what persists – is Sami’s extraordinary handling of pigment, with its hazy diffusions, its clogs and scrapings, its queasy wet-dry quality that recalls a scabbed wound.

If this is a work about the burdens of representation and the weightless dream of ‘pure’ painting, then it’s also one that speaks obliquely to Sami’s biography. Born in Baghdad in 1984, he was enlisted as a youth by Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath regime to produce propaganda murals and portraits of the dictator – the latter a mandatory presence in every Iraqi home. Fleeing in 2003 following the US-led invasion, he fetched up first at a Swedish refugee camp and later settled in London, where he enrolled on the MFA programme at Goldsmiths. Sami’s show is not a straightforward document of this history, but it is a form of testimony, both to lived experience and to how it reprises and reshapes itself in the theatre of memory.

People are conspicuously absent here. Instead, we’re offered empty garments, eerily hushed interiors and items of furniture that

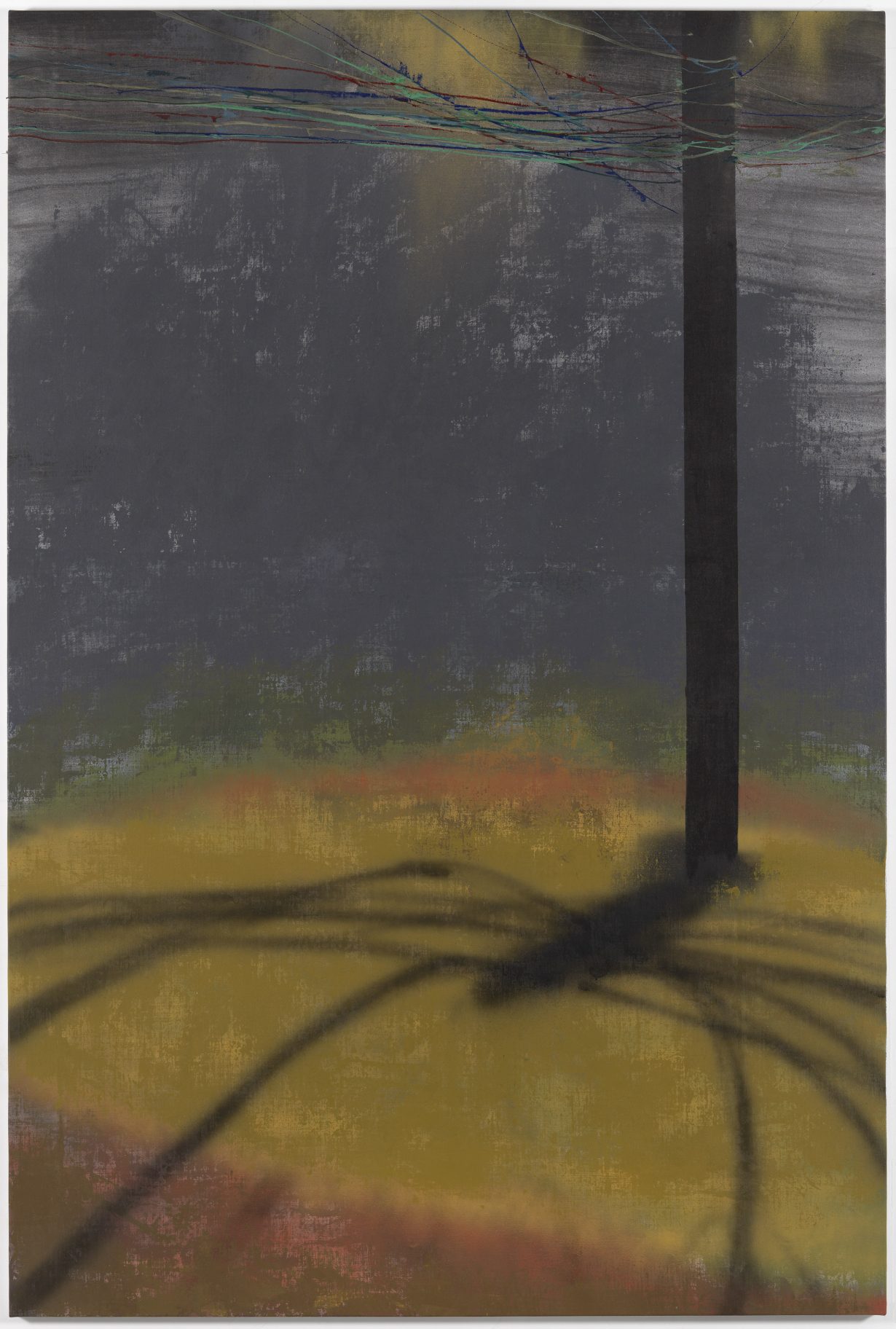

feel like they still retain the warmth of departed bodies. Ten Siblings (2021) recasts its titular human subjects as a teetering stack of mattresses, grimly summoning the poet Thomas Sackville’s observation that ‘sleep [is] the cousin of death’. Similarly, Study of Guts (2022) might depict a bank of sandbags, or military shirts slumped in a quartermaster’s store, or (given their necrotic tinge) a pile of spilled intestines. Horror haunts the most innocuous of scenes. In Electric Issues (2022) the slack cables of a looming telephone pylon cast a shadow that resembles a giant arachnid. We get to thinking of electrodes applied to tortured flesh, and of the ‘spider hole’ in which Saddam famously hid, like some mythic monster, in the days before his arrest.

The largest work in the show, One Thousand and One Nights (2022), is also its most ambiguous. Before us lies a murky, green-toned nocturnal landscape. Amid great billows of cloud, or smoke, scores of white lights illuminate the sky. Too big to be stars, perhaps they’re an aurora borealis-type phenomenon above a dark Nordic forest, or the explosions of a ‘shock and awe’ bombing offensive over a blacked-out desert city, glimpsed through the lenses of night- vision goggles. Either way, it’s a vision of a past on perpetual replay, a story without end.

The Point 0 at Camden Art Centre, London, through 28 May