A new book explores the dilemma of the fan in the age of cancel culture, weighing up moral outrage against a plea for redemption

In the current ‘cancel culture’, the work of canonical artists and authors becomes ‘problematic’ by dint of the personal failings of these (mostly male) creators; artists who have done or (particularly in the wake of #MeToo) are accused of having done terrible things, behaved awfully, abused and hurt people, are, in short, ‘monsters’. In her book of the same name, American critic and essayist Claire Dederer tries to answer the seemingly intractable question that continues to plague this debate: ‘what ought we to do about great art made by bad men?’

To her credit, Dederer takes on the problem from the perspective of the ‘fan’, and Monsters is a sensitive, sometimes overwrought read, for Dederer’s intense personalisation of her subjective investment in both artworks and the artists who make them. Starting from Roman Polanski’s conviction for having sex with a thirteen-year-old girl in 1977, she wends her way through different artists and different forms and degrees of ‘monstrosity’: the abuse and alleged abuse of children and women (Woody Allen, Michael Jackson, Picasso, Hemingway), the virulent or petty antisemitism of Richard Wagner or Virginia Woolf, and the habitual racism of authors of onetime American ‘classics’, such as in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books (1932–43).

Many of these controversies are long-standing, and the yawning historical distance makes this early section of Dederer’s reflection the least convincing: whatever we think of Picasso or Hemingway, however badly we think they treated their wives and lovers, these are people of another age. This isn’t to resort to the (weak) excuse – which Dederer sarcastically dismisses – that ‘The Past is a vast terrible place where they didn’t know better’. As Dederer rightly argues, antisemites like Wagner knew perfectly well what they thought about Jews. But what’s revealing is Dederer’s pessimism that contemporary liberal culture really does ‘know better’ now. The question is not ‘what should we do about sins from the past, now that we’re enlightened?’ she writes, but rather ‘what should we do about sins from the past, when we haven’t improved?’

That sense that things are not getting better underpins the political and emotional handwringing of Monsters, written in the wake of the generational frustration that defined #MeToo and the Black Lives Matter protests, and which bracketed the Trump years. Dederer can’t fully side with the vengefulness and rage of the ‘cancel culture’ period (much as she’d like to admit the just cause of women against the patriarchy), because however well she articulates the case against the ‘monsters’, her heart always returns to artworks she repeatedly insists she loves.

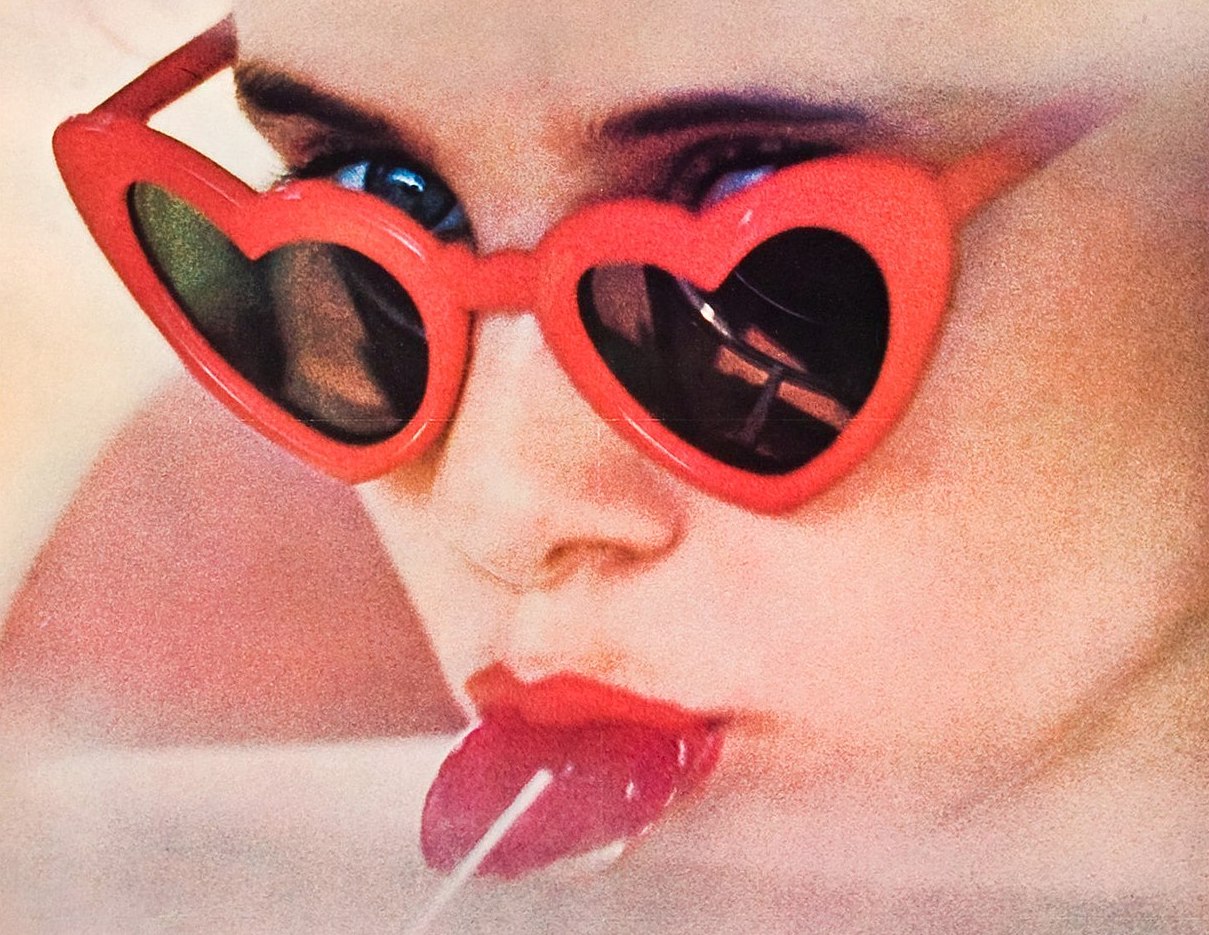

Dederer is a perceptive and engaging critic – the middle, and in a sense pivotal, chapter on Vladimir Nabokov’s writing of Lolita (1955) beautifully sets out how Nabokov must have necessarily inhabited the character of the monstrous paedophile Humbert Humbert, in order to reveal both his evil and mediocrity. In the second half of the book, Dederer turns to the question of female artistic ‘monstrousness’, in a series of striking chapters on women writers who demanded the same freedom as their male peers – that is, the freedom to be free of children – by considering her own ambivalent feelings about Doris Lessing and Joni Mitchell, both great artists who, in Dederer’s telling, abandoned their children in favour of their art.

But because Dederer never finds a way to separate the work from the artist, she can only solve her dilemma ethically, with a plea for redemption, since we are all flawed –‘monstrousness applies to everyone’ – who are we to judge? Finally grating against the self-righteousness of ‘cancel culture’, she concludes that ‘the way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person, or a good one’. True enough, but her trouble is really one of how the claim for ‘cancelling’ bad individuals distorts the question of how art criticism – how to value the artwork, rather than the artist – doesn’t necessarily align with morality or politics. In the end, we shouldn’t be interested in artists for being bad or good people either; one’s moral outrage at their monstrosity fades, artists die and all that’s left is the artwork. Which is the only thing that was ever worth talking about in the first place.

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer. Sceptre, £20 (hardcover)