Charu Nivedita looks on with fear and loathing

Tamil Nadu held its Legislative Assembly elections on 6 April. An election in India is the rendering of a verdict by a tired electorate. The people of Tamil Nadu are pitiful because they do not have a third choice: just Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK). If one is in power, people vote for the other at the next election. Generally, any election in India is a wholesale farce, much like leasing a car. ‘Your time to loot is over. Now we want to give the opposition party its chance.’

Given that this charade has been the trend for several years now, the people of Tamil Nadu had no reason to be surprised by the election results, which were declared on 2 May. They were as predicted: the AIADMK had been in power for two terms; now it’s the DMK’s turn.

In the hierarchy of the Legislative Assembly, the chief minister is at the top, followed by cabinet ministers, members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAS) and finally the councillors. A councillor’s primary role is to represent their ward or division and the people who live in it. Councillors provide a bridge between the community and the council. Residents might expect a councillor to respond to their queries and investigate their concerns. But the reality is somewhat different. And not that pleasing. If I buy an apartment, for example, I must bribe the councillor a hefty 25,000 rupees for a kitchen. (Normally Indian houses have one kitchen but three or four toilets/bathrooms, so out of charity to the common public, they don’t calculate the bribe by number of toilets but on the basis of the kitchen. Any alteration to a kitchen, however, requires an additional payment.)

By the way, no one calls it a bribe in India; it’s a ‘commission’. If I question the act, I had better be prepared for stones to be hurled at my house and for my car or two-wheeler to be torched. Going by the math and the number of apartments in the average ward, the so-called commission would add up to millions. But this is peanuts. At a larger scale, a 100-crore construction project generally allows a councillor to exact a 1 percent fee from the builder. Refusal to pay means the councillor’s hoodlums will ensure that construction never actually gets underway.

My friend owned a medical imaging centre in a remote part of the town. A patient who had her scans done at the centre later passed away in hospital as a result of poor health. The deceased woman’s husband was friendly with the local councillor. The councillor held a peaceful protest – let’s not forget that we are in the land of Gandhi – in front of the scan centre by shouting slogans: a public shaming in broad daylight, as if the imaging centre, in delivering bad news, was responsible for the patient’s death. If the protest leader (in his role as the councillor) is required to intervene and defuse the situation, 25 lakhs will change hands. The deceased patient’s spouse gets five lakhs; our honourable councillor ‘Annae’ (‘big brother’ in Tamil) pockets the remaining 20.

Fifty years ago, a councillor was modest, wore an ordinary dhoti and rode a rundown bicycle. Today, a councillor travels like a Moghul sultan in a lavish display of Scorpio motorcars. Police don’t stop Scorpios; they know who’s inside them. Let us not even picture an MLA’s or a minister’s show of power, given their higher positions in the hierarchy.

How can I decide who to cast my vote for if my choices are a devil and a Dracula? At sixty-eight, I have not voted in any elections to date. I have never disclosed this to anyone within my home state of Tamil Nadu; everyone would denounce me as socially irresponsible. With only 72 percent voter turnout in the recent elections, such revelations by a writer can lead to government harassment – representatives will file court cases saying that we writers are encouraging people not to vote, which is against the constitution and hence antinational. Branding someone as antinational is very easy in India. But in this magazine, writing in English, I can say what I want – no one cares.

Do you know who has a more compelling influence on the people of Tamil Nadu than politicians? Tamil movie stars. I have previously written about this pitiful state. I am at liberty to criticise anyone in Tamil Nadu but the movie stars. Considering their status, if I write anything against them, I will be subjected to people’s wrath, cursed and possibly beaten when I step out of my house.

Banking on his stardom and iconic status, Kamal Haasan (aka ‘Ulaganayagan’ – which roughly translates as ‘Universal Hero’) formed a party and contested the just concluded elections. The sixty-six-year-old thespian has been an onscreen hero for close to 50 years. A movie hero in Tamil Nadu commands a cult status and the lifestyle of Emperor Akbar. Of course, Akbar had 3,000 wives, which is not possible now. Nevertheless, a subject must hold his hand in front of his mouth, palm almost touching his lips, fingers covering his nostrils, while speaking to the emperor. When ordered to leave, he must walk backwards out of the room. Subjects must not wear sandals in front of the emperor; forget interrupting, they mustn’t even open their mouths when the emperor is talking. What can an actor who has led a life larger than Akbar’s for almost 50 years know about the actuality of the Tamil community? While a big-time star demands a 100-crore fee per movie, a sanitation worker’s monthly salary is a paltry 7,000 rupees.

It is amusing to watch someone talking to a movie star – kowtowing and covering their mouth with their palm in an utterly subservient manner. If the star happens to be Kamal Haasan, one cannot open his or her mouth until he has finished talking, even if that would mean four hours of waiting. His superfans prostrate themselves in front of him as if revering him from head to toe, and others bend to touch his feet. But what befell him when he debated in a public forum with Minister Smriti Irani of the BJP is another matter. New Delhi-born Smriti Irani (herself a former model and TV actress, but also from a family with a longstanding involvement in politics) went hammer and tongs after Kamal Haasan, which left him speechless despite a high fluency in English. The reason was simple. While Kamal Haasan was talking for the past 47 years, his movie directors, costars, technicians and friends beguiled him with their sycophancy. The debate proved that actors are a failure in candid discussions. (Although Haasan might have been rendered speechless by the fact that no one fell at his feet!) Smriti Irani gave an effective rebuttal to his queries and posed pointed questions, for which he was at a complete loss for words. The moderator urged Kamal Haasan to talk, but nothing happened.

Vijayakanth (aka ‘Captain’ – Tamil actors often adopt the personas of popular characters they portray onscreen), another reel hero, met with the same fate some time back. Having played roles that upheld righteousness and challenged wrongdoers, he would singlehandedly destroy a villain’s fort or fight the entire Pakistan army onscreen. An innocent commoner might similarly believe that he could rescue the Tamil community. So a party like the DMK, with a solid political foundation in Tamil Nadu, was pushed aside in favour of Vijayakanth’s, which now assumed the role of opposition party in the Legislative Assembly. But lo and behold, he made a mockery of himself and the people of Tamil Nadu by boycotting the Assembly’s proceedings. First elected to the regional assembly in 2006, he had lost both his seat and his deposit within a decade. In a movie, a stunt performer covers for the hero in hazardous scenes; a dialogue writer comes up with the punchlines; and above all, a director controls the actor’s every move. But in real life there are no such buffers. As pathetic as it was to see a reel hero turn into a real comedian and get sidelined, we thought it was going to be Kamal Haasan’s turn next. Instead he lost the election, and we lost the entertainment of witnessing his histrionics in the Assembly.

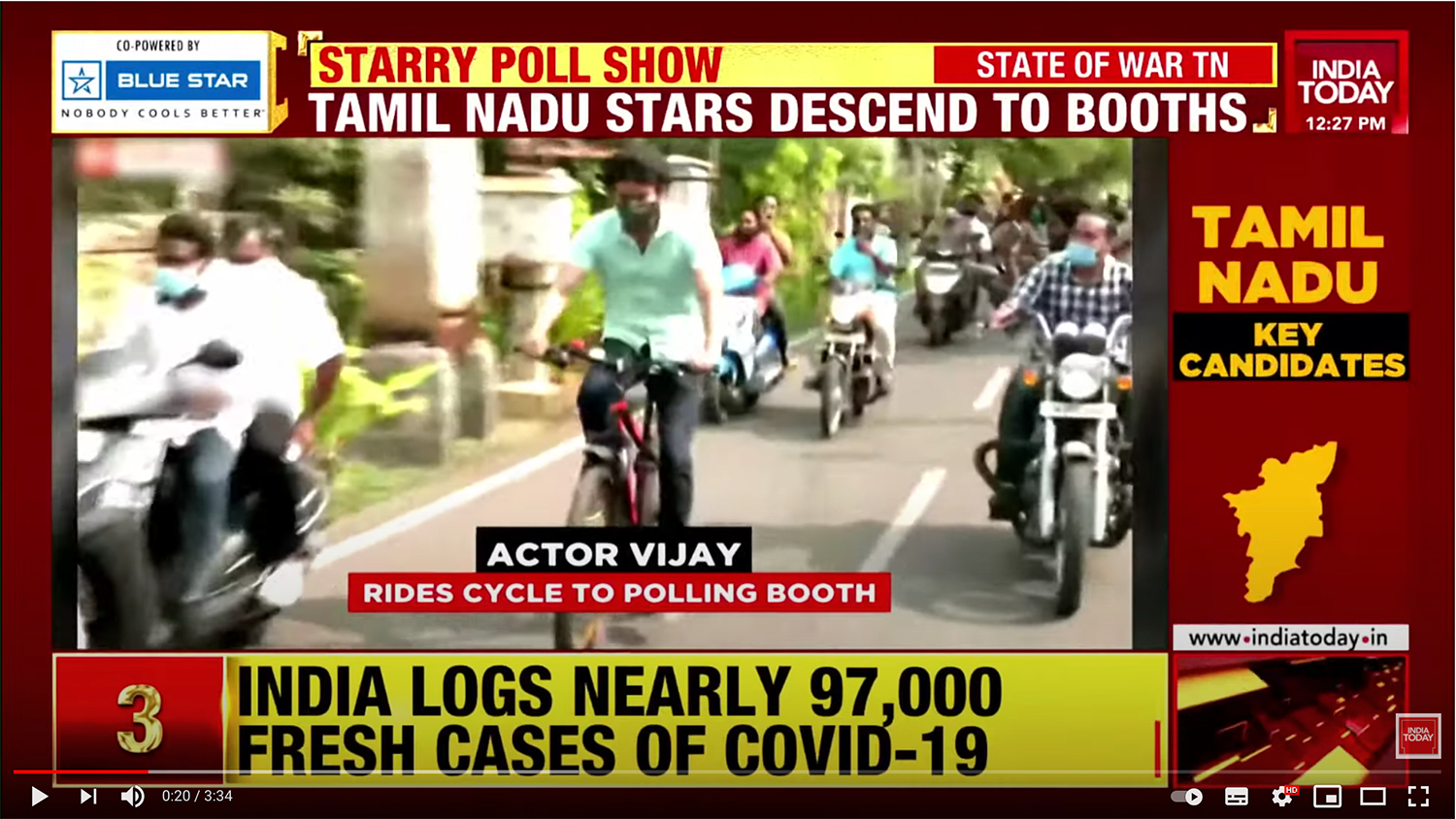

An unusual video circulating on social media on election day demonstrated Tamil Nadu’s weird character. Present-day movie hero Vijay (aka”‘Dalapathi’ – ‘Commander-in-Chief’) cycled 500m to the nearest polling booth to cast his vote. It would be best if you watched this once-in-a-lifetime video yourself. If you can’t or won’t, imagine how it would be if God descended to earth and rode through town on a bicycle. There were motorbikes on either side of him and another hundred behind. Anticipating his arrival at the polling station, police were on hand to hold back the hordes of fans and reporters so that he could inch his way through. Already I can hear the chirp of a wall lizard in my ears: “This is the next Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu”.

The scariest front in Tamil Nadu politics is the entry of movie director Seeman. Unlike other political parties, his Naam Tamilar Katchi is founded on principles rooted in racism and fundamentalism. He is Hitler, Pol Pot and Mao Tse Tung, all schemed into one. He could not make it big in movies, but he has gained popularity among the less educated, the unemployed and rural youth. That only a hardcore Tamilian should be allowed to rule Tamil Nadu, that educational institutions must close and that people should return to an agrarian existence are just some of his demands. Recently he even spoke out in protest of COVID-19 vaccines. When Hitler delivered his demagogic, deranged speeches, it would appear as if the microphone bent in submission. Chaplin made a joke of this in one of his movies. I get a similar feeling when I watch Seeman. He may not yet have a seat in the Assembly, but his words kindle rage among the youth. It makes me anxious about the future of Tamil Nadu.

Translated from the Tamil by Srividhya Subash