How might sentimentality for the recent past be transcended and rewritten?

For some time, I’d planned to reread Peter Hujar’s Day – a transcript of a conversation between Hujar and the writer Linda Rosenkrantz in which the late East Village photographer recounted everything he had done the previous day, 18 December 1974 – on its 50th anniversary. The transcript, 27 pages, lightly edited and published as a short book in 2022, documents Hujar’s riveting cadence and amusing digressions. For him, 18 December had been a normal and even, in his words, ‘wasted’ day, full of ringing phones and visitations: the critic Susan Sontag and the artist Ed Baynard called about a gallery exhibition and sexual needs, respectively; an editor from Elle came to Hujar’s 2nd Ave loft to acquire prints for the magazine without saying how much he was to be paid; Hujar went to the Lower East Side to photograph an uncooperative Allen Ginsberg for The New York Times. In the evening, Hujar developed what turned out to be mediocre photos of the poet after being treated to a $7 takeout by the curator Vince Aletti, who needed to use Hujar’s shower. The day is relatable, even if one must breaststroke through the proper nouns to get to the emotion, and this seems significant since Hujar and the milieu of which he speaks are no longer accessible to contemporary New Yorkers. As the novelist Stephen Koch writes in his introduction to the transcript, real estate developers and the AIDS epidemic effectively demolished the Downtown art scene of the late 1960s to mid-90s. Consequently, ‘twenty-first-century generations have come to view what used to be as paradise lost’.

I encountered a visual artefact of this bygone New York when I saw On the Barricades, an exhibition at Microscope Gallery of Narcisa Hirsch’s Super 8 and 16mm videoworks from the 1960s and 70s. Muñecos (1972) shows the late Argentinian artist handing out palm-size figurines of naked babies – cheap-looking, plastic – on 5th Ave, as well as in London and Buenos Aires. The film is silent, but we learn from the exhibition materials that Hirsch said, “Have a baby!” to passersby as she distributed the dolls, cheekily critiquing the Argentinian government’s natalist policies of the time. Across the three cities reactions are mixed, but the film portrays New Yorkers as the most bemused, zooming in on men in suits with knitted brows and pursed lips (in this city, it’s easy to come off as a stereotype). Hirsch’s action takes place adjacent to a picket that was part of a farm workers’ strike, and every so often we see a sign that reads, ‘Boycott Lettuce’, and sense the subtle chaos of politically motivated art sharing sidewalk space with a political demonstration. I realised how quickly a few minutes of shaky camera footage from the past could trigger nostalgia or anemoia, a sort of secondhand sentimentality that Hujar was perhaps instinctively foreclosing when he insisted that 18 December 1974 was just another ‘wasted’ day.

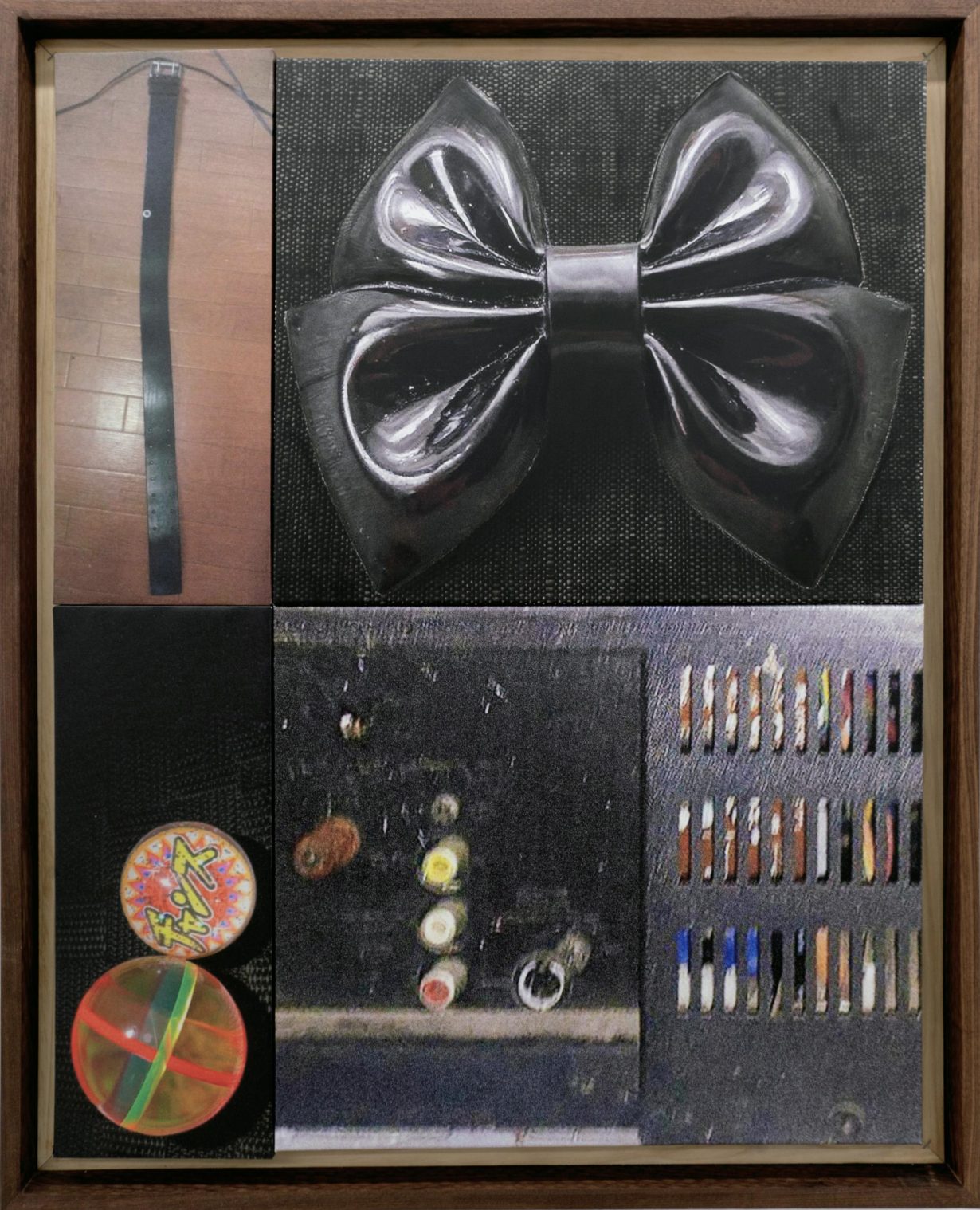

Sara Yukiko’s XO Show at Gern en Regalia, another exhibition that stood out in December, involved an inventory of artefacts from a more recent past. Yukiko took images from Mercari, a resale site, and printed them on canvases of various sizes, some of which are Tetrised into large rectangular frames. Most of the imagery had to do with feminine fashion and toys like stuffed animals and anime figurines (I imagined seeing Hirsch’s plastic baby dolls here). The canvases seemed intent on scrutinising, with voyeurism but without judgement, the enigmatic thought process behind listing, for instance, the half-used turquoise eyeshadow palette pictured in blOO (2024) or the flimsy watchband shown in a corner of Cinch (2024) and staging and cropping low-resolution photos of these products. What a shame, the sellers might say, to let this junk go to waste, and what a shame, XO Show suggested, to let images of this junk die on the internet.

Likewise, Rosenkrantz tried to rescue 18 December 1974 from obscurity, by recording her friend’s fleeting memory of it, with all its quirks and imperfections, its unsentimental poeticism. Their dialogue was still on my mind when I saw Hunter Reynolds / Dean Sameshima: Promiscuous Rage, a show at P.P.O.W. of two artists whose work deals with twentieth-century queer histories. The front of the gallery was mostly devoted to the late Reynolds’s snapshots of flowers, lights, ocean waves and scenes from a room in Fort Lauderdale’s Imperial Point Hospital, stitched into ‘photo-weavings’, a form the artist began exploring when a friend of his succumbed to AIDS during the early 1990s. These were interspersed with text-based works by Sameshima, the junior of the two artists. Here, the difference between nostalgia and the kind of asynchronous mourning often enacted in exhibition spaces – in this case for both victims of the AIDS epidemic and Reynolds, who passed away in 2022 – became clear. It is hard to picture ‘paradise lost’ when confronting snapshots of a patient in a hospital gown next to closeups of a toilet bowl, even when these images manifest as richly saturated c-prints.

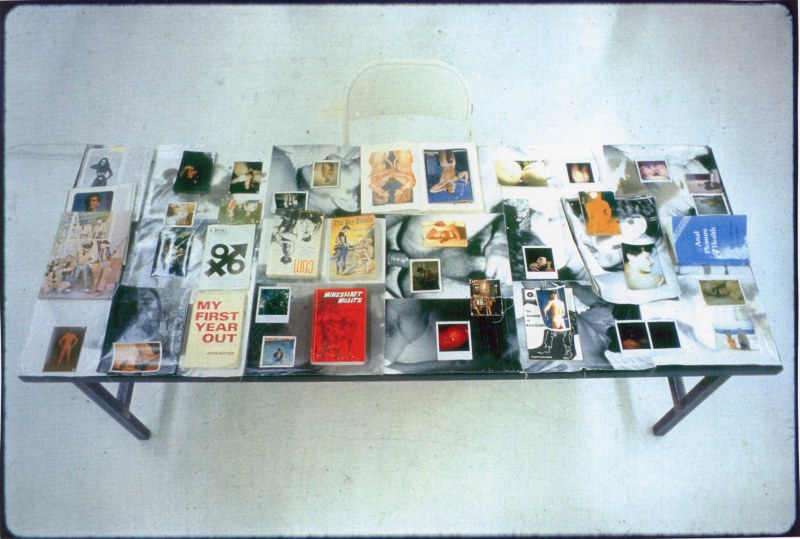

However, what struck me most was the terseness and opacity of Sameshima’s works – canvases silkscreened with phrases like ‘Anonymous Deviant’ and ‘Anonymous Public Sex’, pithy appellations that referenced neither a time nor place and avoided mentioning AIDS by name, preferring instead the moniker ‘Anonymous Illness’. Juxtaposed with Reynolds’s copious output, Sameshima’s works appeared not only unsentimental but even aloof and irreverent. In the back of the gallery, Reynolds’s Dialogue Table 3, My First Year Out (1992), a table strewn with vintage paperbacks, smutty magazines from the seventies and eighties and weathered Polaroids of men in various states of undress, seemed to spill its guts to Sameshima’s taciturn offerings on the walls around it. I wondered, then, if it was precisely because Reynolds’s visual record – like New York lore from the latter half of the twentieth century – disclosed so much so memorably that Sameshima’s pieces are able to explain a bit less and imply a lot more.