As art lovers converged on the city for its high fair season, Jenny Wu found resolve in the quiet among the chaos

The socially understood meaning of a photograph is what Roland Barthes called its studium. Any detail that arrests the mind in a private and inexplicable way is a punctum. Looking back at a snapshot of this past May in the New York artworld, the picture is dominated by events whose social and historical significance staunchly occupied the field of Barthesian studium. Art lovers converged on New York to attend Frieze, NADA, TEFAF, 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair and the rest. Spring auctions netted $1.4 billion, despite low anticipated sales and a ransomware attack at Christie’s. Protests against institutional complicity in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians continued at art museums, notably at the Whitney during its Free Friday Night event on 3 May.

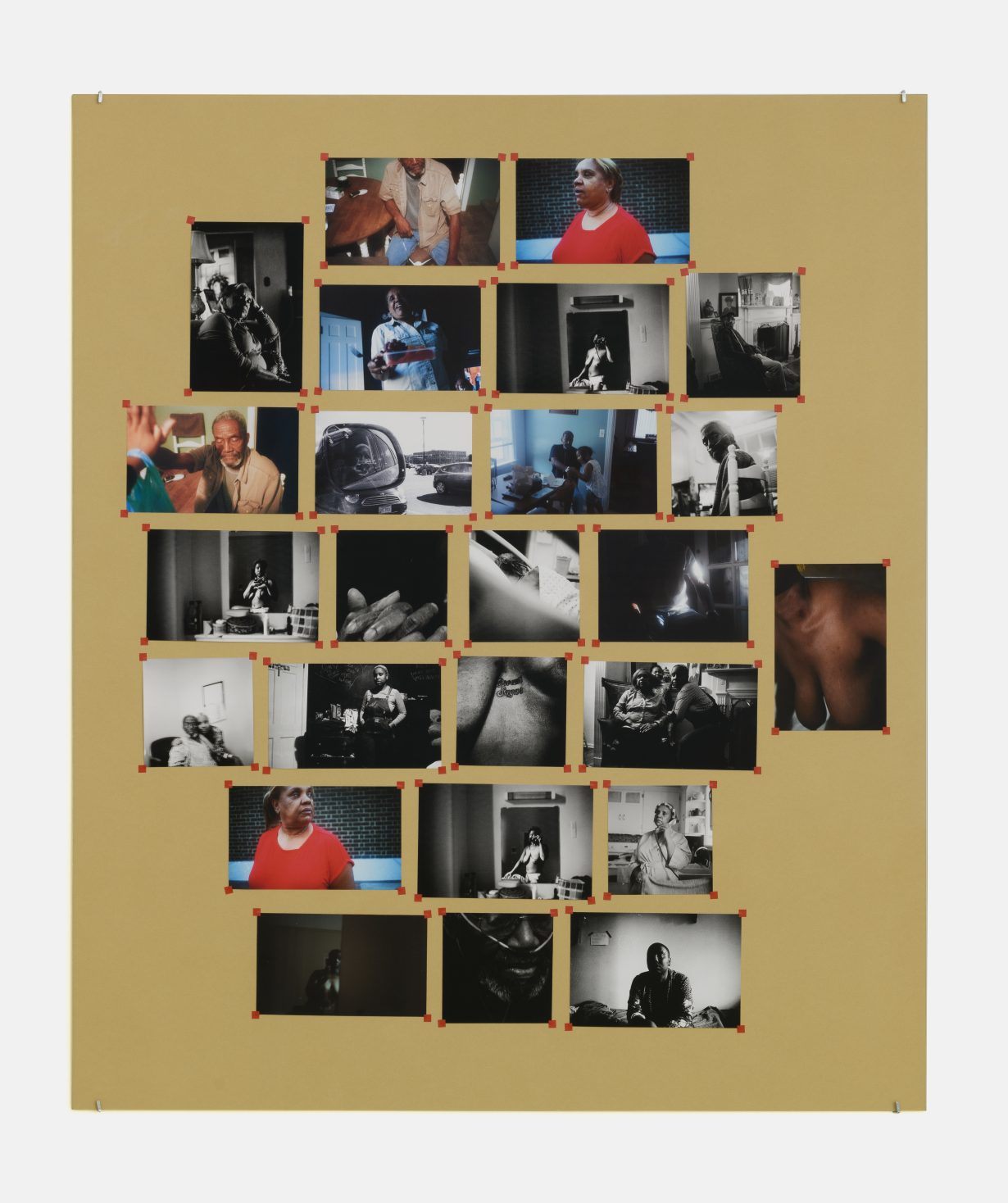

Somehow, amid this frenzy of activity, I had an encounter with a quiet photograph by Shala Miller of their smiling mother holding a Tupperware container full of fruit. It was one of the few colour photos in the group show Forks & Spoons at Galerie Buchholz and is part of a group of 25 archival pigment prints titled Tender Notebook (2016–24). The subject appeared grand in the low-angle shot – the mother’s half-lit face magnetic – but to me, the plain plastic box was the punctum here. It echoed the austerity of the muted yellow background on which the series was laid out like notices on a community bulletin-board.

Then there was the scene in Teresita Fernández’s film Cuajaní (2024), screened in the basement of Lehmann Maupin, in which two women were sorting grain on a table in their home in rural Cuba. The punctum in this image was the older woman’s left hand, which she had pressed across her breasts as she leaned against the tabletop. While her other hand, manicured with dark polish, picked busily at the mounds of grain, her left hand rested in a kind of inscrutable gesture that, like the staffless fingers of Rodin’s L’âge d’airain (1877), trafficked in an obscure zone between utility and expression.

Towards the end of the month, I found myself moved by packages of resin-entombed mochi in Sandra Ono’s sculpture show Kaeru at Bibeau Krueger. These faux readymades, dedicated to the artist’s late grandmother and arranged on the gallery floor in stacks of three and four, were untitled but numbered, like the kind of supermarket delicacies one might bring to a gathering of friends. Yet, trapped in a transparent solid, they were also relics of the present, lonely and untouched, like the food at the party that no one eats.

This is the first instalment of a new monthly column by Jenny Wu