An aerial perspective from above the clouds, at turns sinister and celestial, offers a route into alternative and nonhuman ways of seeing

September: the month the New York artworld starts running again. This time around, though, we seemed to be suspended in uncertainty. The talk of the town – the market downturn (or ‘slowdown’ or ‘reset’ – whatever you want to call it) – coloured everything from insiders’ murmurings about the US’s impending presidential election to the overly conservative presentations at the Armory Show, hardly assuaged by the wan consolations online: ‘The art market is ridding itself of froth and making room for… art that has the potential to stand the test of time’ (Cultured); ‘true aficionados now have a chance to reconnect with art’s intrinsic value’ (Artnet). Yearnful caution and drifty agnosticism mingled in the galleries, where plenty of works still managed to make an impression.

This included a shaky, streaky 26-minute video composed of aerial views of Manhattan and the Bronx by Anna Rubin titled The Gram (all works 2024), on view at Maxwell Graham. What appeared at first like a glitchy screen recording of someone surfing Google Street View turned out to be footage filmed by a homing pigeon equipped with a small camera. Rubin’s tactic reminded me of those employed in espionage in the First and Second World Wars, and, more recently, in environmental activism by the artist Beatriz da Costa, who outfitted pigeons with miniature air pollution sensors that transmitted their data to an online server. Like an artworld denizen in autumn, Rubin’s avian surveyor covered a lot of ground quickly, seldom stopping to steady the frame. The furious intensity of its flight superseded the information it captured.

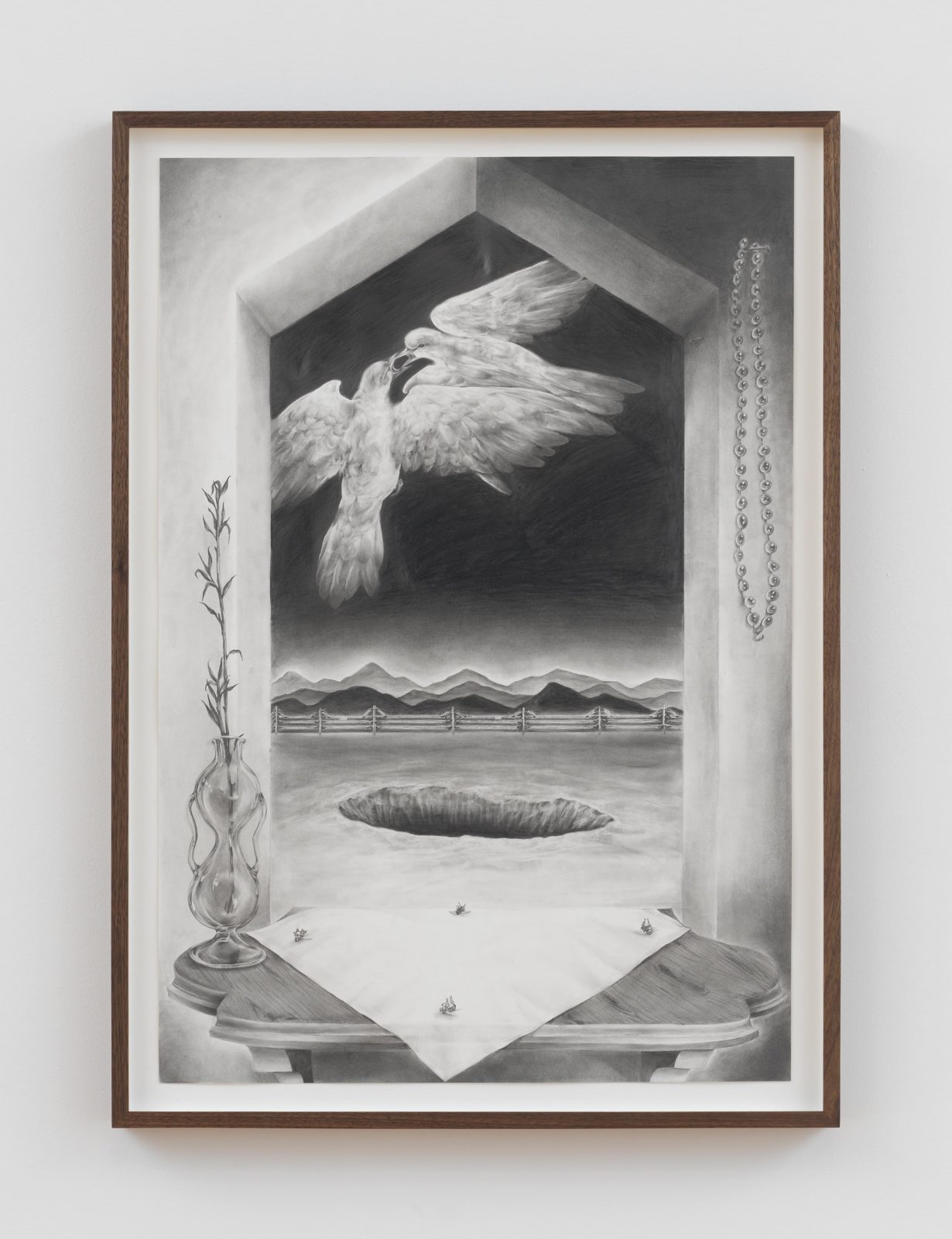

Birds also appeared in R. Jamin’s solo show at David Peter Francis. In their home of Los Angeles, the artist once worked as a carer for flightless doves. In their graphite drawing Foundation Pit, a pair of doves interlock their beaks like esoteric augurs; real feathers could be found swaddled in cotton and enshrined over a plate of lodestones (Valentine II) and balanced on a metal nail protruding from the gallery wall (Valentine IV). Another gathering of white fowl materialised in Craig Jun Li’s show at Rainrain, in an untitled, framed collage of Polaroids embellished with a fragment of a vintage clock the shape and size of a diary lock. This collage was paired on the wall with one of a suite of lo-fi photographs printed on mesh and stretched over motorised wooden rods that undulated, massaging the images from within.

Labouring bodies in an image-dominated milieu, Li’s makeshift machines seemed akin to Rubin’s pigeon. Machines that were sleeker but no less strange performed in an exhibition at Petzel by Kristin Walsh, whose work I was introduced to at Helena Anrather, one of over a dozen galleries in New York that closed this year (another statistic that hung over my rounds). The working end, Walsh’s latest show, featured eight aluminium sculptures resembling ubiquitous features of MTA infrastructure such as looped stanchion poles, train engines and glowing green lamps, which were covertly magnetised to attract an array of knickknacks to their surfaces. During my visit, a six-sided die skated around the canted turnstile handle of Indicator no. 5 like a moth skittering on a lampshade. Elsewhere, in the metal cylinders of Engine no. 12,matchsticks rose and fell to a mechanical rhythm in uncanny unison, small but stalwartly embattled against gravity, against time.

Later, I saw Nengi Omuku’s debut at Kasmin, which wasn’t full of moving parts so much as it seemed, as a whole, to be breathing. Here, eight oil paintings on sanyan, a traditional Nigerian textile, were suspended from the ceiling and floated several centimetres above the floor. In the largest work, I Can’t Feel My Legs 2, human forms also float in a celestial abyss, gathered ceremonially around a central figure lying on a bed of bruise-coloured clouds. The asymmetries, imperfections and perforations in the paintings’ surfaces gave the feeling of limbo a sense of texture and dimension, for a moment turning the in-between into a place worth feeling out, if only to see where it takes us.