What can an American history of leftist zine distribution teach us in the era of ICE, MAGA and AI memes?

Tucked away in a small room on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a zine library is packed with cardboard storage boxes piled high on spindly metal shelves. The sides of the bookstacks are covered in stickers that read ‘BRING ON THE FUCKING HATE’, ‘INVASIÓN’, ‘BLOWUPNIHILIST’. A narrow desk beneath the window AC holds a display of free pamphlets and newspapers like The New York War Crimes; a photo of a child in the Jenin refugee camp is printed on the issue’s cover. This library in the Clemente, a Puerto Rican and Latinx cultural centre, belongs to squat-turned-arts-nonprofit ABC No Rio, and it was being manned by executive director Gavin Marcus when I visited. Zines today, he told me, function much as they did in the late twentieth century and are once again becoming integral to leftist social movements. “A lot of that comes from younger generations,” he said. “There’s this well-placed mistrust in social media and our always-on, always-connected society. Zines pull people out of their bubbles.”

Indeed, zines are experiencing a renaissance in cities across the US as their online counterparts – social media platforms controlled by private companies – are increasingly subjecting users to profit-driven surveillance and censorship. In New York alone, exhibitions devoted to printed ephemera and DIY publications have appeared everywhere from the Brooklyn Museum to the Grolier Club and Baruch College’s Mishkin Gallery; last year the Black Zine Fair at Powerhouse Arts drew over a thousand attendees. Meanwhile, The Guardian reported that zines have been crucial for offline information-sharing, teaching people in the US ‘how to protect one another from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)’ or ‘how to resist the Trump administration outside No Kings protests’. And it seems the detractors are aware of their political power: in July, an artist in Texas was arrested and prosecuted for conspiracy for transporting a box of zines.

Like a protest, the creation of a zine will often signal the presence of likeminded people committed to a cause. However, we cannot quantitatively measure whether any particular publication directly inspires political action the way, for instance, it’s apparent that the nationwide strike on 30 January resulted from the circulation of online videos depicting the state killings of Alex Pretti and Renée Good whose names have been emblazoned on protest signs across the country. The surge in popularity of these scrappy, transient missives – whose contents range from the practical how-tos of the anarchist distributor and publisher Sprout Distro (‘10 Steps for Setting Up a Blockade’ (2015); ‘An Abbreviated Do It Yourself Guide to Making a Jail Support Plan’ (2025)), to the irreverent fictions of Vaginal Davis’s Fertile La Toya Jackson (1982-1991) – reflects a collective yearning for alternative spaces, in addition to the space of the protest, in which to autonomously rehearse what historian Sean Lovitt calls ‘symbolic acts of dissent’.

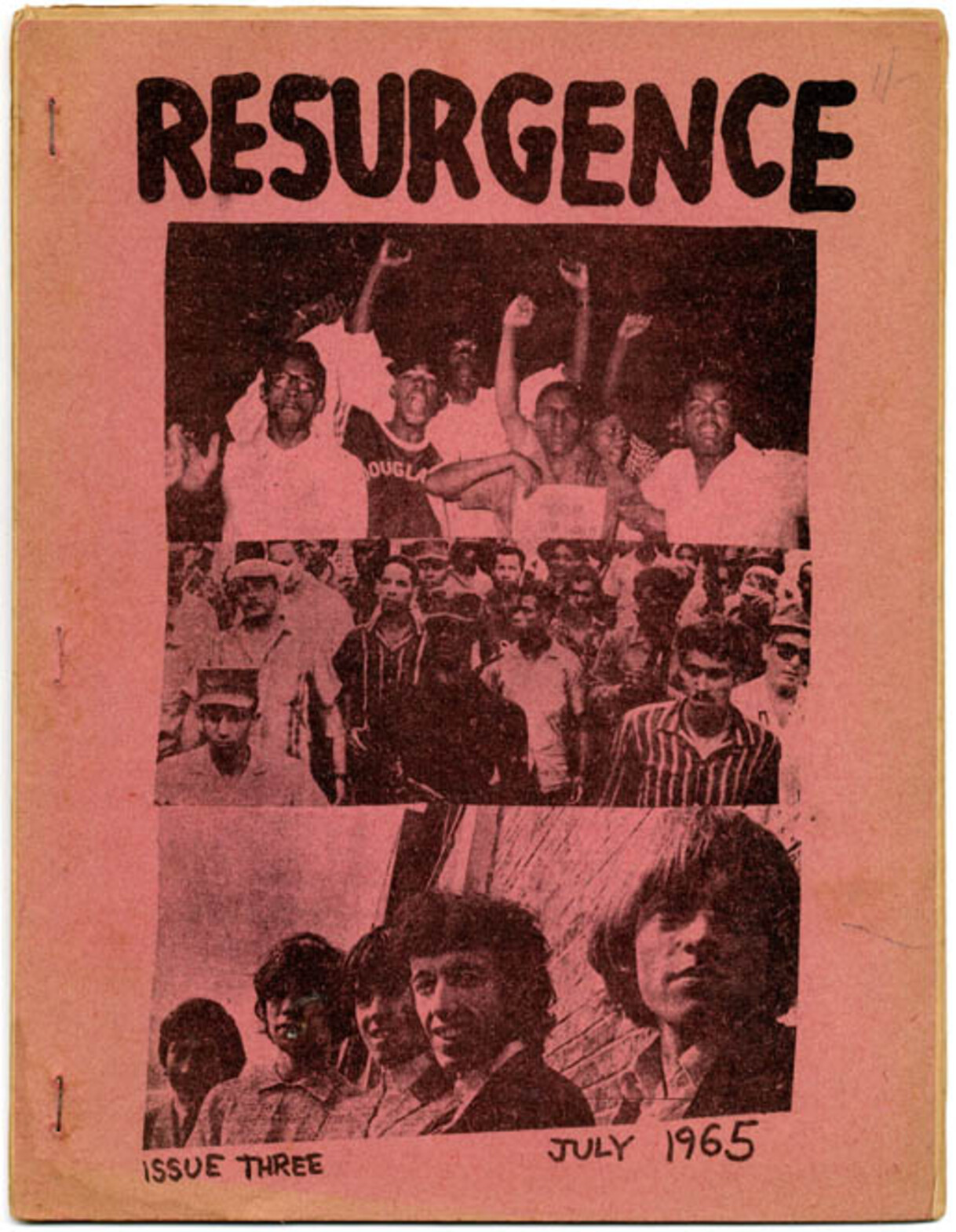

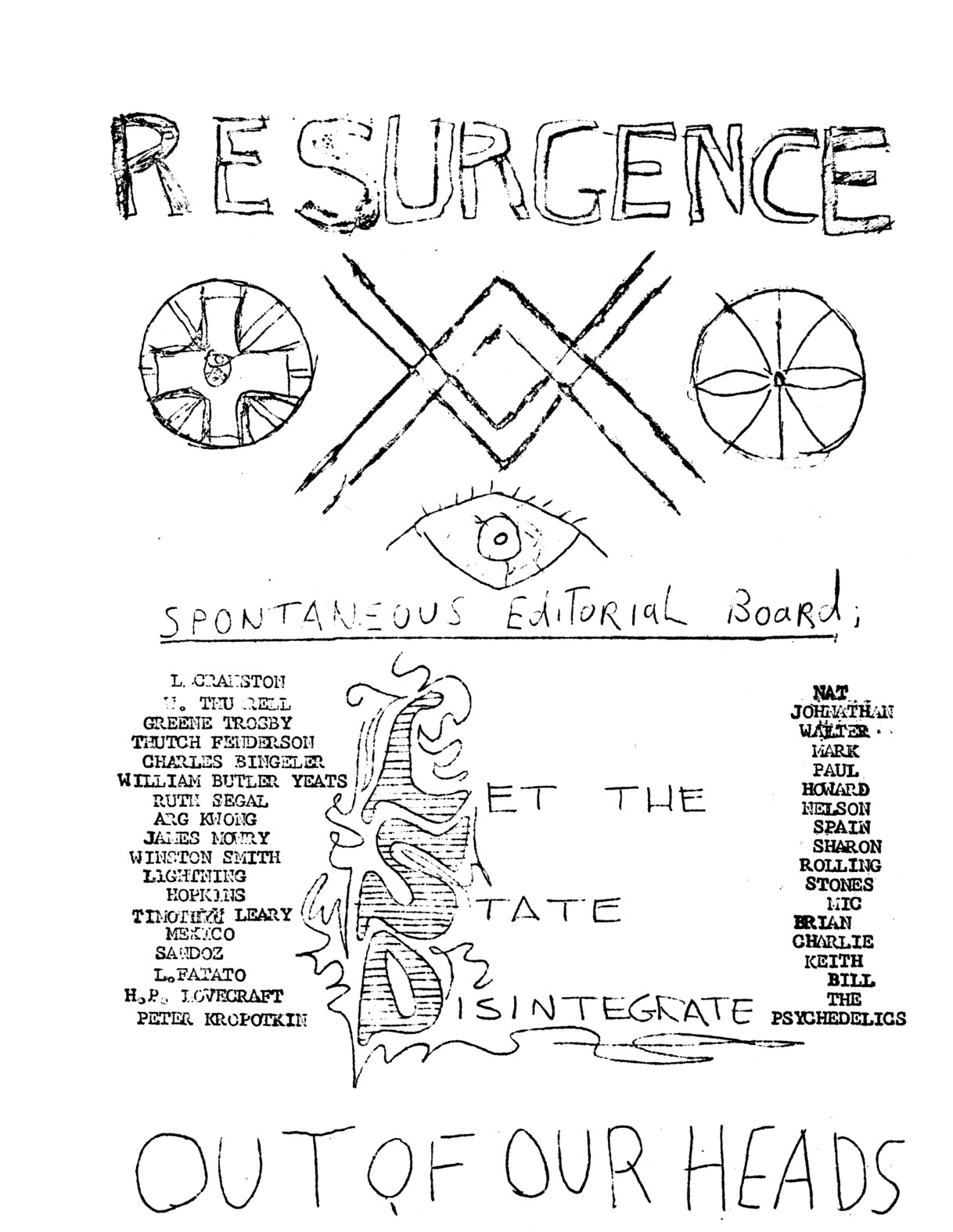

In the 1960s, in a hotbed of leftist affinity groups based around Tomkins Square Park that included Up Against the Wall Motherfucker and ESSO (East Side Service Organization), the teen anarchists known as the Resurgence Youth Movement (RYM) produced a zine titled Resurgence, which is currently the subject of an exhibition at Interference Archive in Brooklyn. Resurgence emerged during the frenzy of DIY publishing known as the Mimeo Revolution, when access to mimeograph machines, letterpress and affordable offset printing fueled an unprecedented proliferation of magazines and poetry books remembered fondly for their shagginess and experimentation. Printed on one such machine obtained from the Marxist theorist Raya Dunayevskaya (who ran her own radical newspaper News & Letters), Resurgence was handed out for free, mailed to readers, or sold at radical bookstores. It expressed the credo behind RYM’s direct actions against imperialism and racism.

In a 1964 letter to a friend in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the group’s 17-year-old co-founder Jonathan Leake wrote that Resurgence would cover ‘topics ranging from Assaults on Popular Culture […] to theoretical articles of revolutionary technique, to news of rebel youth activity abroad in Europe, Africa, etc’. The first issue included an unauthorised translation of Pierre Mabille’s essay ‘Le Surréalisme, un nouveau climat sensible’, which, through its inclusion in Resurgence, symbolically positioned RYM as heirs to André Breton’s Surrealist mantle. There was a report by Leake, writing under the pseudonyms ‘Thutch Fenderson’ and ‘John Dix’, on the 1964 Harlem uprising, an event that inspired him to form the ultraleft affinity group. Later issues featured poems, manifestos, essays on magic, automation and sabotage. ‘As American youth,’ reads a paragraph in Resurgence 12 typed under a sketch of a four-armed eagle flanked by hammer and sickle symbols, ‘we are responsible to all humanity, certainly not to the Death Machine that our society has become.’ A more obscure contribution reads, ‘I am Thutch, man of mind. I am a stoned anarchist. I eat the food of earth and ocean, the flowers of the sky and the fish of the trees’, under what seems to be a portrait of Thutch with the numbers 666 inscribed on the bridge of his nose. With its propulsive mix of insurrectionary thought and provocative hand-drawn art, in its prime, Resurgence was ‘a beacon that guided young militants to emerging political trends’, Lovitt observes; nevertheless, it ended following the untimely death of RYM’s other co-founder Walter Caughey in 1967 and became yet another ‘forgotten publication’.

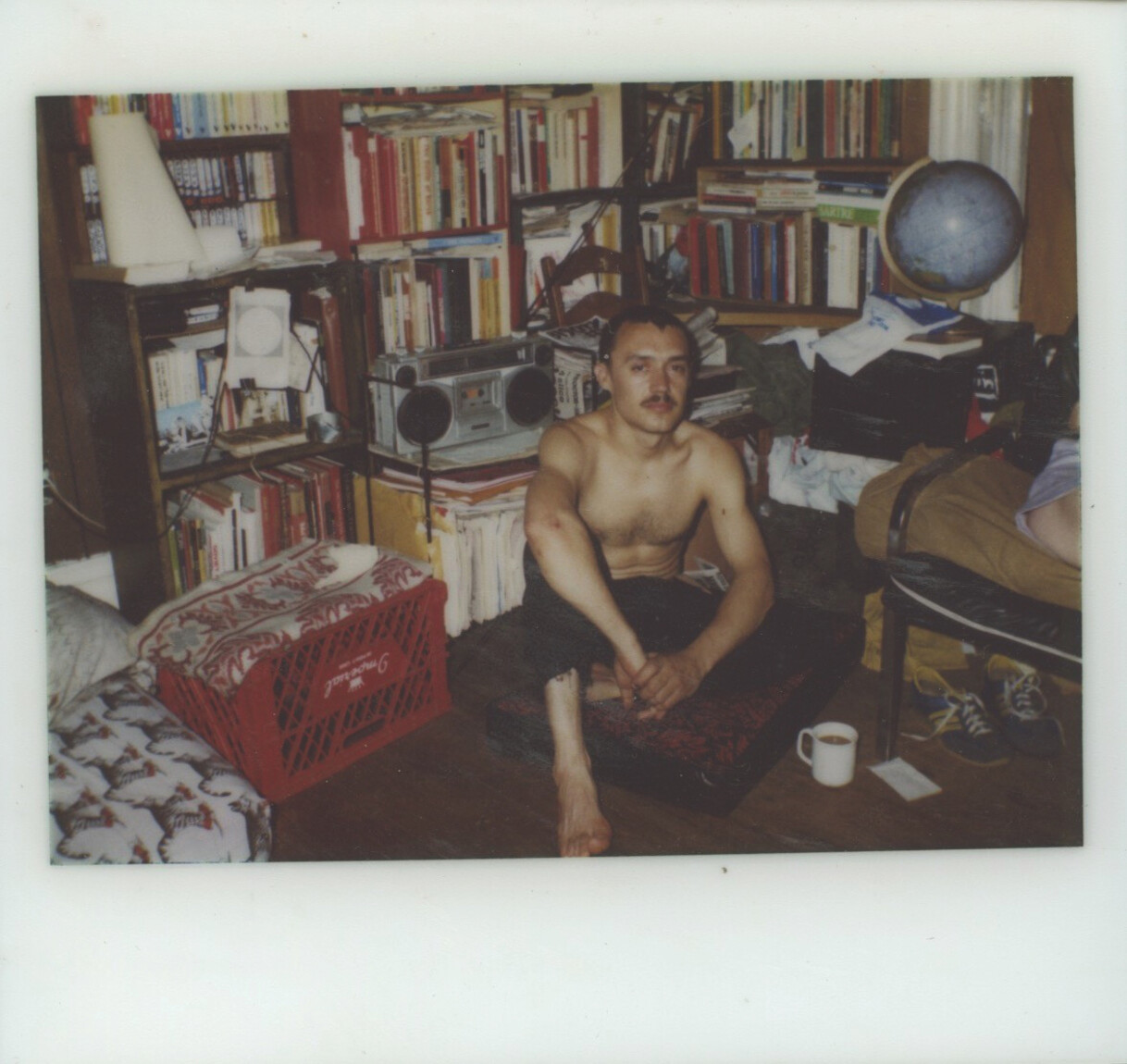

Leake’s other writings, including his eight-issue WARCRAFT pamphlet (1988–89)and Antipocalypse (n.d.), now rest in plastic sleeves in ABC No Rio’s quaintly disheveled archive. Encountered today, the writing in these yellowing Xeroxed dispatches is easy enough to describe – it’s mystical and bombastic, florid and unwieldy – but difficult to summarise and even harder to commit to memory.

They resemble what Nadia Asparouhova calls antimemes: the opposite of memes, which spread easily because they are bite-sized and ‘wrapped in lightweight packages’ that travel nimbly through collective consciousness. Memes are viral posts and political slogans we feel immediately compelled to circulate; antimemes, Asparouhova writes in her book Antimemetics: Why Some Ideas Resist Spreading (2025), are niche articles that express or test our politics that we share quietly in group chats, or not at all. Memes, reinforced by repeated exposure, linger in the mind, while antimemes lapse into periods of dormancy or permanent obscurity, despite their initial impact.

From this dichotomy, we can infer that ideas transmitted during protests are largely memetic – chants are rhythmic, memorable and spread efficiently – while those in zines are semi-private, uneven in tone and subject, directed often at very specific, high-context audiences – and consequently antimemetic. Which is to say, much as their admirers, archivists and historians may wish to preserve them, the contents of historical zines like Resurgence are liable to fade as soon as they’re read today, if they’re read at all. But this is not cause for mourning. The very ephemerality, fugitivity and context-specificity of political zines, both of the past and those currently distributed in response to crises like the ICE raids in the US and the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, become means of evading many of their censors and opponents. Perhaps successful activist literature is that which ultimately gives birth to a new and better political context and, in doing so, writes itself into obsolescence.