When documentary practices entered the stage of contemporary art big-time during the 1990s, they were often referred to as ‘reportage’. They were said to give witness accounts from conditions, situations and events pertaining to both the personal and the political, both micro and macro. In this way they began to fill a gap in the transforming media landscape of many parts of the world. Instead of investigative journalists reporting about hidden facts nearby and unknown things abroad, we learned about such things from individual artists who spent time and energy digging through the turf both at home and (often far) away.

When I recently saw the St Petersburg-based collective Chto Delat’s new video The Excluded: In a Moment of Danger (2014) at the São Paulo Bienal I was struck by its power precisely as an eyewitness report, offering a complex and difficult account of current affairs. With unusual proximity, it talks about what has happened in Russia in the last six months, about the takeover of Crimea, the Boeing crash in Ukraine and other less mediatised events. But rather than being documentary in its formal articulation, it is highly staged and theatricalised, made collectively with graduates from Chto Delat’s own School of Engaged Art.

This is the kind of dissent that is absent from Russia’s mainstream media

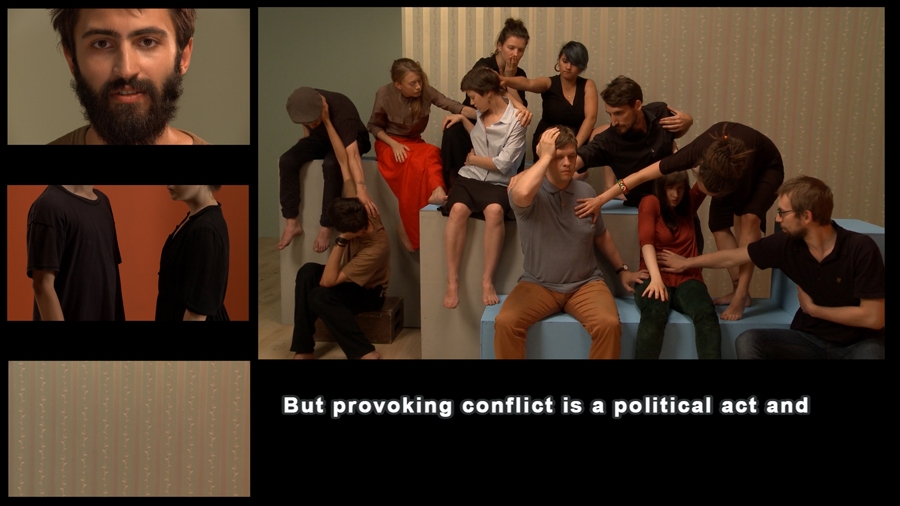

The Excluded… is an hour-long film divided into 12 chapters, each featuring the barefoot graduates as themselves, arranged in various strictly choreographed constellations inside a studio. It is a room that is both domestic and institutional, with support structures like exhibition pedestals placed on the floor. The participants repeatedly log on to their social networks, only to realise that nothing has changed. Standing up, they give their coordinates in time and space. “I’m 7,000 light years from the N6C6611 cluster of stars annihilated by the explosion of a supernova and 1,000 years before its disappearance from our field of vision” is one, “I’m 2,000 kilometres away from the battle for the Donetsk airport and 20 years from the first war in Chechnya” another.

The camera behaves like a searchlight, moving slowly with and around the agents in the room. In chapter four the participants realise that they are part of society and also responsible for it. While sitting in a row, they touch their own bodies, then start to move up and down in spasms, only eventually to fall down on the floor. The following chapter sees the introduction of ‘the ear of society’, with a giant ear entering the room, and they retune their voices, literally, to be heard. Most of them end up sounding like animals. At the same time they lean on each other, and on the pedestals, as if collapsed.

In the section where they begin to listen to one another, there are glimpses of what it can be like to live in Russia today: while one woman is ‘fucking scared’ as a lesbian, the split in society is likened to civil war by another woman. A man claims that his nonconformist tongue is his conflict. Families are divided on Putin and Crimea, according to another participant. When they are seeking points of no return in history, the signing of the act for annexing Crimea is indeed the first one. Others suggest the trial of Pussy Riot, 9/11, the US invasion of Iraq – which coincided with the birth of that man’s daughter – the Russian presidential election and the first congress of the opposition and its failure to unite the various groups. The most striking suggestion is the 1999 bombing of Belgrade by NATO, after which a conservative turn demanded that citizens of Russia not only sympathise with their fellow Orthodox Serbs but also hate Albanians. Despite the fact that most people had never heard of them before. This is the kind of dissent that is absent from Russia’s mainstream media.

Although The Excluded has given me flashbacks since I saw it, it suffers from not having been through enough formal scrutiny. In Niemeyer’s Bienal building it is presented as an installation with a large projection at the centre and three flat screens on the side walls. The latter show details of the performance in the studio, and some reference material. When I later watched The Excluded online, it was all one image, clarifying that the work is not working as an installation. The theatrical aspects do the right thing within the frames of the image but not beyond it.

Not only is this theatricalisation special in terms of ‘reporting’ – with precedents like 9 Scripts from a Nation at War (2007) by Andrea Geyer, Sharon Hayes, et al, which is now in MoMA’s collection – it highlights the need to take issues of articulation as seriously as content. Too many artworks in general and documentary practice in particular get away without paying enough attention to the implications of how things are being done. Nevertheless, I hope that The Excluded, like 9 Scripts…, will enter a major collection as quickly as it gave us an account of recent Russian affairs.

This article was first published in the November 2014 issue.