Perhaps an indication of the richness of Zach Harris’s artistic practice is the wild variance with which viewers describe the references and precedents for what they see. One can churn into the discussion everything from Tibetan mandalas to Islamic tiles to Kandinsky, but nothing specific seems to stick very long. Instead, the word ‘vision’ steps forward. Harris’s painting conjures visions, in the sense that he imagines the inner tremors that remain unseen in the ordinary world, the vibrancy that animates our idea of something beyond us, whether an afterlife, a heightened state of consciousness or parallel dimensions.

The completed works, made from wood and often distinguished by exquisite carving on their surfaces, read somewhere between folk objects and aged devotional panels or even icons. They feel ancient, like riddles from another time whose keys have been slowly lost over generations. Harris seems a romantic of the sort who processes a world of broken forms, as travellers once regarded the buried ruins of Rome or revelled in the depressed interiors of decaying European estates. These forms had purpose, but now that purpose has fallen from memory, and Harris aesthetically wanders in this rich and mysterious space.

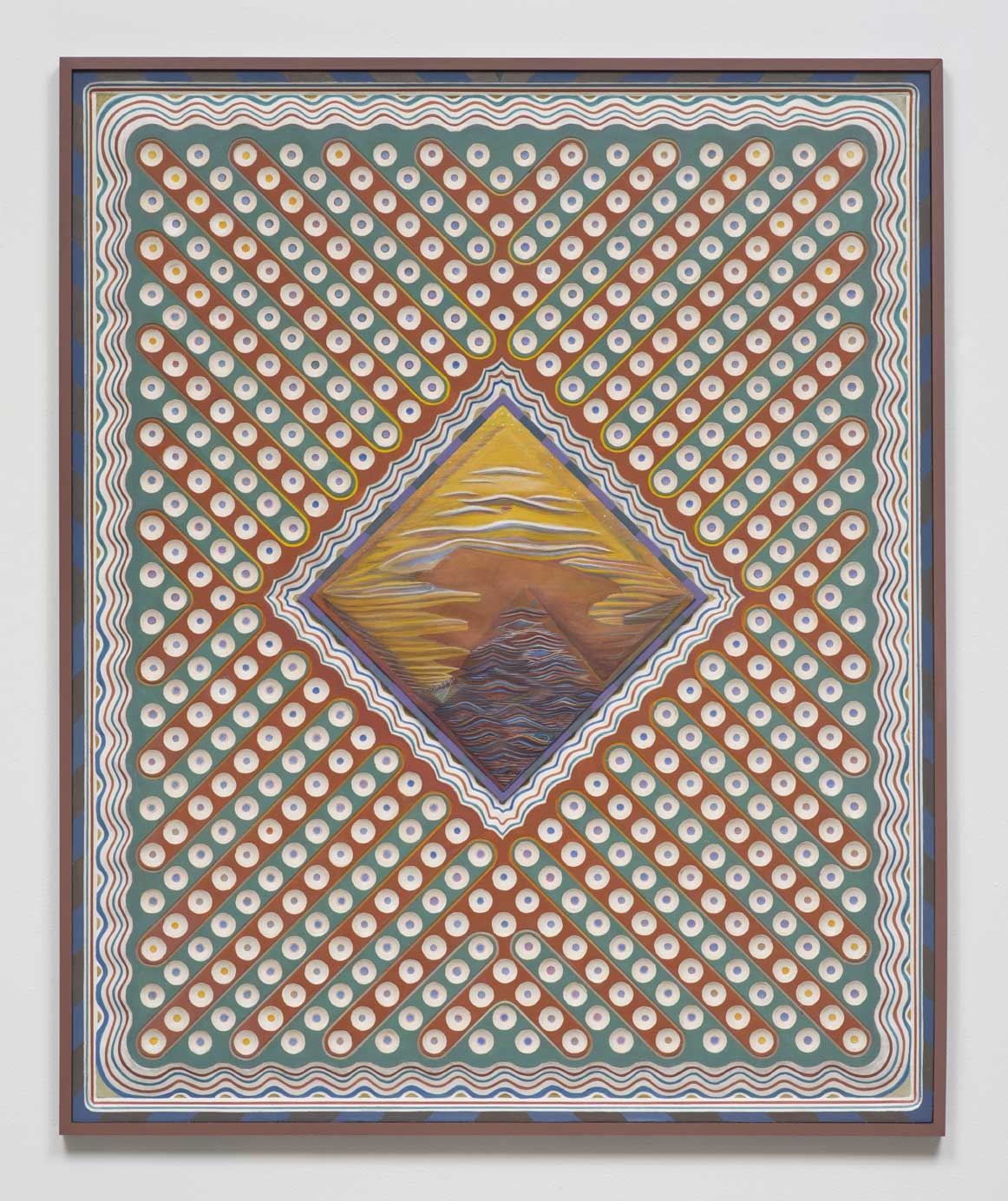

Wheel in Picture Light (2011–13) is an accumulation of diamonds that seem to originate from the bent crag of a mountain, and a floating mass becomes what may be a temple. Surrounding the painting is a band of yin-yang symbols, which would read as insufferably hippie in lesser hands (especially in Los Angeles), but which Harris somehow pulls off. Cumulatively, these symbols offer folk cosmologies that transcend the dubious or campy through their exquisite crafting and art-historical density. They’re at once serious paintings and the efforts of an eccentric, but an eccentric who has been at work long enough to refine his efforts into something solid and believable.

The largest painting in the show, Belvedere Torso/Finger Scales (2012/2013), could be seen as a statement on the scale of an altarpiece, and it is a remarkable joy of seeing the work in person that the rest of the pieces in the show teach you how to view it. In terms of relief, there is almost none in the painting, just a simple routered edge. After encountering the carving and patchwork relief of the other works, however, your eye is tricked into seeing the shadows as chiselled and optically deep. From a tiny landscape of Stonehenge-like standing stones emanates a series of hallucinatory mountains that become, if not a godhead, then, at minimum, echoes of the infinite.

Are these paintings spiritual visions? The answer is no: they are too nostalgic, too reliant on prior aesthetic ideas of what visions are supposed to look like. Instead, they are visions in a late-nineteenth-century-symbolism sort of way, when one could reach back into an art-historical past just distant enough to appear fresh and newly mysterious. The Pre-Raphaelites come to mind, as does the Nabi group, not in how Harris paints but in how he longs for lost ritual, how he assembles traditions into a synthetic but hopeful resonance.

This review was first published in the October 2013 issue.