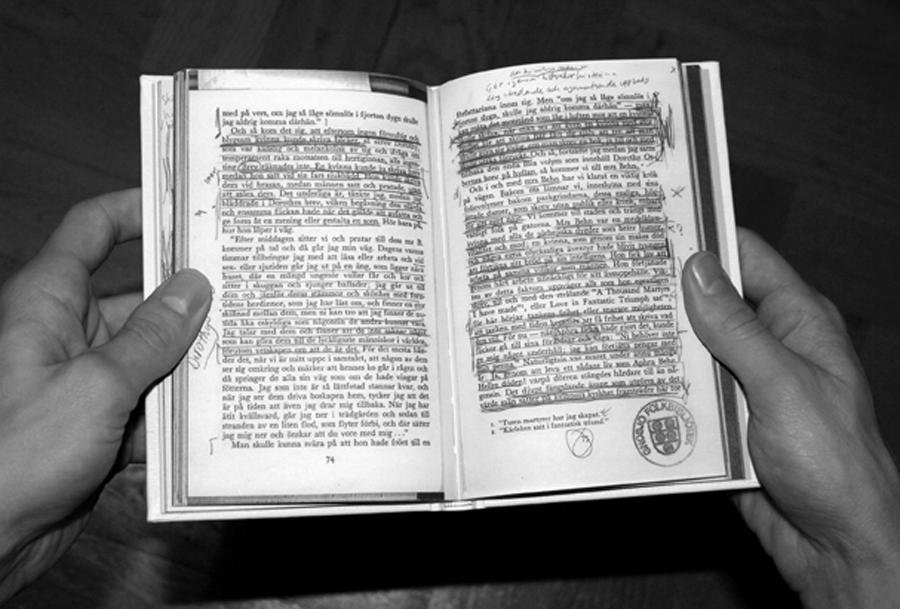

I imagine myself browsing the shelves in a quiet public library in Stockholm. I am in the literature department, towards the end of the alphabet, randomly taking out books, flicking through them while catching a sentence here, a paragraph there. Suddenly I am holding a slim volume full of notes. It is Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’ (1929) in Swedish (in which language it was first published in 1958). Someone has underlined passages and written comments in the margins, wanting to enter into a dialogue. Not only with Woolf but also with me and other subsequent readers. Half a page is marked with a thick pencil line accompanied by the words ‘it is noticeable that she is upper class’; further down it says ‘integrity’ and ‘I do not agree’.

In fact I am standing in front of one of 12 white vitrines on the top floor of Malmö Konstmuseum, looking at Kajsa Dahlberg’s A Room of One’s Own / A Thousand Libraries (2006). It’s the centrepiece of the exhibition A Voice of One’s Own: On Women’s Fight for Suffrage and Human Recognition. The vitrines are filled with photocopies of each page of Woolf’s book, assembled from all the copies of her classic that the artist could get hold of via Sweden’s public library system. As a further part of the project, those pages on which various readers have left notes have also been collected in a beautiful little white book (an edition of 1,000 copies).

A Room of One’s Own / A Thousand Libraries came about as a response to an invitation from the nonprofit space Index in Stockholm. During Mats Stjernstedt’s long directorship (2001–11), a stream of great artworks, this one among them, were made within the framework of Index’s programme. Without it ever being publicly articulated, many of the individual projects, as well as their coming together under the general umbrella of Index, evoked a sense of consistency and urgency. Each work was clearly different from the next, but they all tended to take their respective author’s oeuvre one step further, in their sensitivity and awkwardness, poignancy and poetry. On the part of the institution, there was a wish to support a precise selection of emerging artists and forgotten or unknown old-timers, and to facilitate their creation of new work, an important value in relation to programming an institution.

Today I would say that Index as an institution during this time had a clear sense of quality, consciously or unconsciously. Right now it is crucial to make such a sense of direction public, to put forth the reasons for doing what we are doing. It is not about quality in terms of eternal values and canons, classics and masters. Quite the contrary. In a cultural condition marked by assessment and control, and driven by quantitative measurements, it is urgent to propose and insist on values and notions of quality different from the ones that both the commercial art market and a new public art management system impose on us.

We are about to drown in rubbish art and populist programming. Politicians and bureaucrats pride themselves on providing more art, relying on the blunt value of quantity to back them up

Why? One obvious reason is that we are about to drown in rubbish art and populist programming. Politicians and bureaucrats pride themselves on providing more art, at least in the part of the world where I am based, relying on the blunt value of quantity to back them up, just as the dominant forms of evaluating the performance of institutions privilege high visitor numbers, media hits and budgets. All of which means that a higher quantity of substandard work features prominently in commercial galleries and public spaces alike, finding fast ways to trickle into so-called public institutions and the media. But then how do we know what has quality?

By arguing for our case, in relation to the case of others. In this struggle of values, curators and directors have consciously to communicate their choices of artists, themes, methods, etc. Quality is about openly supporting and fighting for something – insisting on the fact that this ‘something’ is more important, necessary and / or relevant than everything else – and to constantly revise the criteria driving this. It is about distinctions. It is about arguing for ‘this’ and not ‘that’. But not as an arbiter of taste; rather, such distinctions function as markers of urgency. This urgency can pertain to aesthetics, ie, the way in which the artwork is articulated (the ‘how’ question), and to subject matter (the ‘what’ question), conditions of production, context, etc, but more than anything else it requires a certain amount of courage, to be tough and stake such claims, and to have the guts to deselect people you previously staked claims for.

In the wake of the establishment of cultural theory and critical studies, and in light of poststructuralism’s deconstruction, old hierarchies have thankfully crumbled. We are all more than aware of that. Today debating quality has to do with publicly questioning and scrutinising what we decide to do, and acknowledging that absolute notions of quality are being replaced by mutating, context-sensitive negotiations that generate qualities in the plural. So please don’t offer me any more art per se; all I want is good art.

This article was first published in the October 2014 issue.