The champagne-fuelled anxiety is gone – now it’s ominousness, even nostalgia, when you log in to Frieze’s viewing rooms

‘Some scientists,’ Frank Zappa used to say in interviews, ‘claim that hydrogen, because it is so plentiful, is the basic building block of the universe. I dispute that. I say there is more stupidity than hydrogen.’ In a similar spirit, we might say that the foundational material of the contemporary artworld is average art. Toss a brick in a gallery district and you’ll hit some – work by young practitioners that, however long you linger and poke at it, scans as competent but says nothing new, work by big names on autopilot, etc – and, in terms of response, it delivers the worst the artworld has to offer: a sort of null, why-did-I-bother flatlining. Some days, after touring a bunch of such exhibits, you might long for not even a good show but a fucking atrocious one, just to feel something. Emerging from such a debacle not long ago, I facetiously asked my wife if she’d enjoyed it. Do I have tomatoes on my eyes, she said. (Derision is idiomatic.)

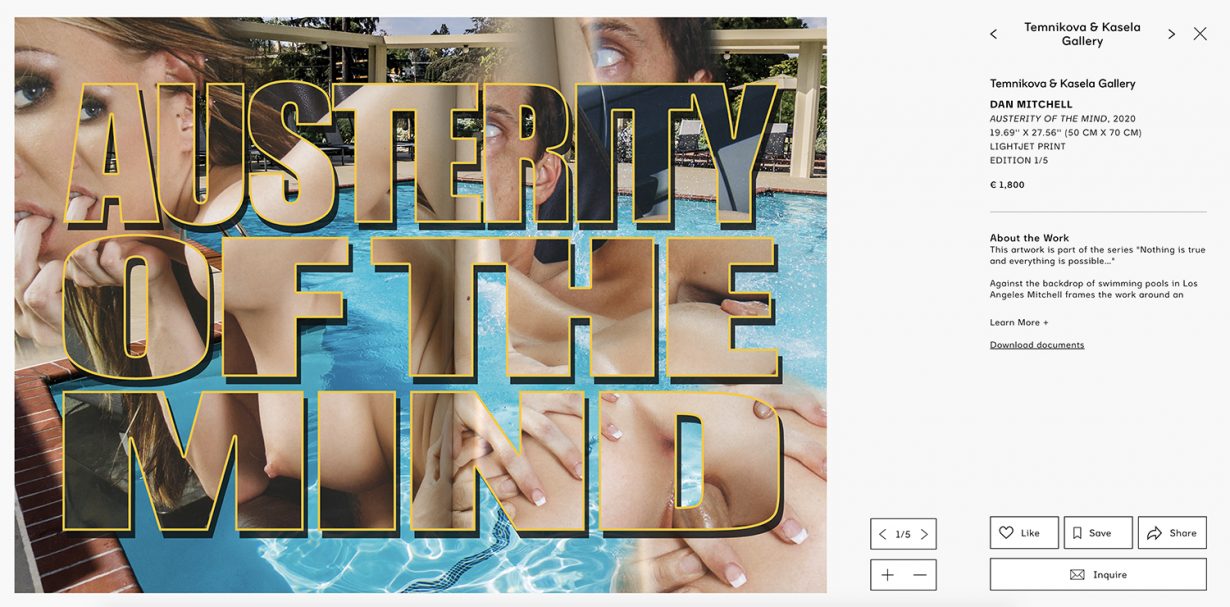

Anyway, at this point I’d like to thank the Frieze Art Fair, which I saw this week via my laptop screen, for multiple complexly structured parcels of affect. Admittedly, nosing through online viewing rooms, there were numerous or perhaps innumerable works that in themselves didn’t quicken the pulse a jot, just like the real thing: galleries sallying forth their big names, or works on paper by their big names, the whole experience enlivened mainly by the visibility of the prices and the absence of any sense of rush on the viewer’s part. There was a ‘like’ button to smash below each artwork; I preferred not to. What the fair and the paraphernalia around it managed to achieve remotely, though – and this admittedly is the perspective of someone who missed the IRL satellite and piggybacking events in London – was an ambient melancholy intermingled, on occasion, with bathos.

At one point I received an email invite to an ‘online book signing’, at which it was promised I’d have a brief window of time to interact with the artist. Skipped that. On the fair site, meanwhile, viewers were encouraged to type their name into digital guestbooks to let the galleries know they’d clicked on the pages. (Probably, given the inestimable leakiness of the internet, the exhibitors have other if more laborious ways of finding out.) I appreciate the inventiveness of these substitutes for intimacy – necessity being the mother of invention – without quite being accustomed, yet, to feeling somewhat sorry for galleries or fair directors. The work on show, meanwhile, tended towards sublime detachment from current events, either because their effects aren’t showing up in artistic practice yet or because it would spook and depress those famously skittish beasts, collectors. (At least one exhibition I saw recently in Berlin was, according to the artist, scrubbed clean of aspects that might recall the pandemic.)

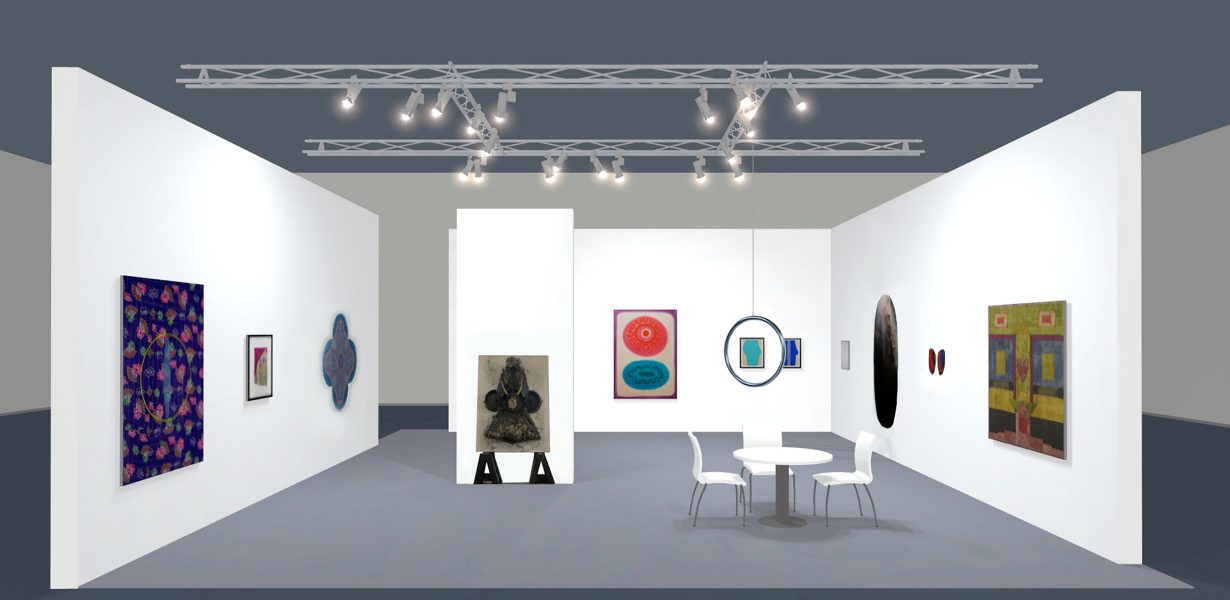

Onscreen, flat room after flat room of a parallel dimension, often with the same expensive chair in the right-hand corner for scale and lots of Average Art alongside it, began to evince a strange, dissociative feeling. I zoned out, and found myself mindlessly toggling between two images of a Tobias Rehberger neon that reads ‘Without Love’ (£20–50k), one in a lighted space and the other in darkness. Maestro of the light switch, that was me. I clicked my way towards the Focus section, where as expected there were some younger names to take note of, but then made the mistake of opening an online interview – also on the site – with Kim Jones, artistic director for Dior Menswear and Fendi womenswear and couture, who had been invited to pick his favourite works from the fair and say a few words about them. Thanks to Kim, I now know that Howard Hodgkin’s work is ‘all about colour’, that Bill Viola is ‘very inspiring’, that a particular John Chamberlain sculpture is ‘unusual, exciting’, and that the interviewee is on first-name terms with the artists he likes. Reading this felt not unlike watching a car slide sideways down a distant hillside, or perhaps like eavesdropping on conversations in the Frieze VIP bar, back in the day. As for the talks, I’m glad the discourse is being furthered but haven’t gotten around to them yet, having a backlog of podcasts to listen to.

What was absent from the digital fair experience was, of course, the tiring aspect of tromping round booths; when your feet don’t hurt and your irritability level is relatedly lower, you’re more open to the spectacle accumulating, click by click: technology-enabled survival on the part of galleries and fair franchises with added art-fashion crossovers alchemising stupidity. What was especially good was that I could see it from Berlin without a mask on, and absorb plenty of information pertaining to the infrastructure of contemporary art: if not quite fair-as-Gesamtkunstwerk, this was an artefact of a moment in deep flux, in which even middling art was tangibly wreathed in a larger mood, if hardly saved by it. At Frieze London in bygone days, that mood might have been perky, nervy, champagne-fuelled excitement – now it’s ominousness, diminishment and even nostalgia, both short- and long-term. But at least, even through the screen, you could feel it.