One notable statistic to describe the last decade is this: there are more curators than ever before. The number of graduate programmes increased tenfold over the last decade, churning out eager, highly-qualified curators despite the field’s minuscule overall growth. The Internet scaled into a chaotic web during the same period, and curating entered the popular imagination as a self-appointed term for high-functioning OCD that offers VIP access to the good stuff. For a moment, everything was curated. They are middlemen, distributors, liaisons, or conduits – that curators head a laundering scheme grants them a seat at the table with the financial elite. Curating is what authority looks like in an attention economy: the power to craft the historical narrative. If this desire is what’s behind it, it’s surprising the output is so benign. For my part, I’m a recovering curator. It just felt too icky.

Curating is what authority looks like in an attention economy

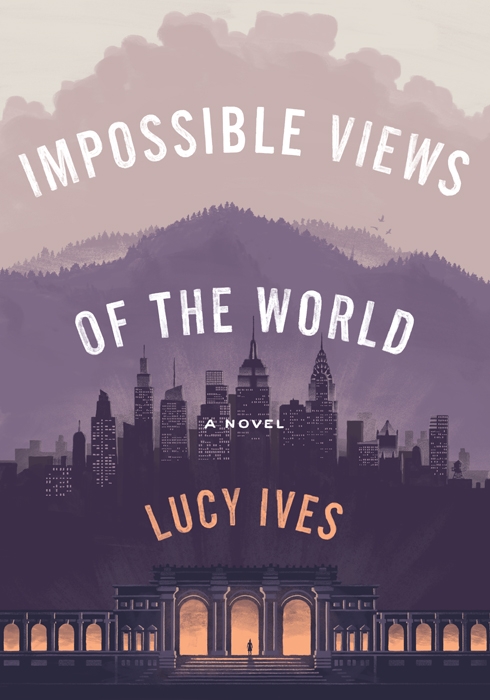

Curators may be a necessary evil though: for all the powerbrokering, they are the stewards of history, and protect us against #fakenews. I have a feeling all the bureaucracy is just so that they’re the only ones that get to touch the art. In 2017, it’s a trope prime for the satire that Lucy Ives’s debut novel Impossible Views of the World delivers in the form of its protagonist, Stella Krakus, an archetypal curator. She works in the farcically named Department of American Objects at the encyclopaedic Central Museum of Art (CeMArt); she’s dedicated, if ambivalent to the ethical contradictions of her craft, on the spectrum between compartmentalisation in the name of ambition, and measured aloofness to anything outside of her research. Many of her relationships are transactional, which makes her a difficult character to be friends with, though an aspect of my discomfort can also be attributed to the artworld (or any niche community) being reimagined for a mass market audience (the book’s published by Penguin).

Nonetheless, Stella is a deeply uncomfortable character, and reflects many of the emotionally cooler conventions of the artworld’s truly bourgeois side. On the one hand, it’s a mystery novel: the department’s longtime registrar disappears, and while covering for him, Stella uncovers all sorts of historical intrigue about the museum. On the other hand, it’s an eventful, if transitional moment in Stella’s life, though we seldom leave the museum during the week the novel takes place. The most influential people in her life are her ex-husband, Whit Ghiscolmbe, her mother, Caro, and her colleague with whom she had an affair, Fred Lu. She’s got good reason to be mad with all of them – Lu’s truly deflating statement that he can’t love but one person crowns the selfishness and microaggression that Stella awkwardly endures. It makes her come across as equivocal or conniving, but in general, she’s expedient, because she’d just like to work. Rather than enjoying that privilege unmolested, though, she’s usually called upon to perform loads of emotional labour.

Ask yourself the last time you dated outside of your professional circle and you’ll hit on Stella’s particular anger and ennui

Ask yourself the last time you dated outside of your professional circle and you’ll hit on Stella’s particular anger and ennui. It’s a precarious world that emotions can seem to jeopardise. What truly animates the novel, however, is Stella’s research into the museum’s archive and collection. Here, she has control; here she let’s out her rage; and here she is the redeemer. Her scholarship is supple, confident, and often funny. In her interpretations we see Stella more fully accounted for, though she sometimes presents various historical documents such as journals, word docs, novels, emails, magazines, maps and even architectural fragments in full. With Stella’s character, Ives observes a fundamental contradiction about persona, and about desire itself: that it’s constructed out of many people’s work.

Impossible Views of the World, by Lucy Ives, published Penguin Press, $25 (hardcover)