At a recent panel discussion I took part in at the MiArt fair in Milan, myself and curators Bartolomeo Pietromarchi and Sebastian Cichocki – both of whom have overseen national pavilions at Venice – arrived at some startlingly firm conclusions. (You’re not really supposed to do that in art fair conversation programmes: equivocating waffle is more the order of the day.) Our mutual consensus to the subject we were handed – ‘Thinking beyond the Nation in the National Pavilion Model’ – was that the national pavilions at the Venice Biennale should stay, but that we should destroy the nation state. The Giardini would then become a memorial to an absurd historic situation in which people drew lines in the earth, hoisted a piece of fabric the colours of which denoted an arbitrary set of values, and then sat tight, fearlessly defending their patch against their fellow humans the other side of the those said lines.

Like a good western colonialist I started at the long boulevard headed by the British and French pavilions

The world has failed to take our advice. And so, walking through the Giardini yesterday and running into friends, one fell into the strange conversational patter of “Hong Kong is good”, “Belgium is boring”, “Venuzuela isn’t ready yet, total disarray”, “meet you in Denmark”. Like a good western colonialist I started at the long boulevard headed by the British and French pavilions: these seemed to have gone with the principle of ‘fill the pavilion with stuff, make it big and spectacular’. I get a text from a Brazilian friend which (she’s good on satire) reads ‘Come over to our Third World side’, which drew me across the small bridge across the canal which divides the main Giardini area from the more secluded eastern area. There, it struck me that if we’re stuck with the nation state, then it is for the countries who are often overlooked on the so-called international art circuit that the national pavilion model works best. (By and large the artists exhibiting in, say, the British, German, American and French Pavilions don’t really need any more publicity – and Venice is, not just an exhibition, but a publicity vehicle too.)

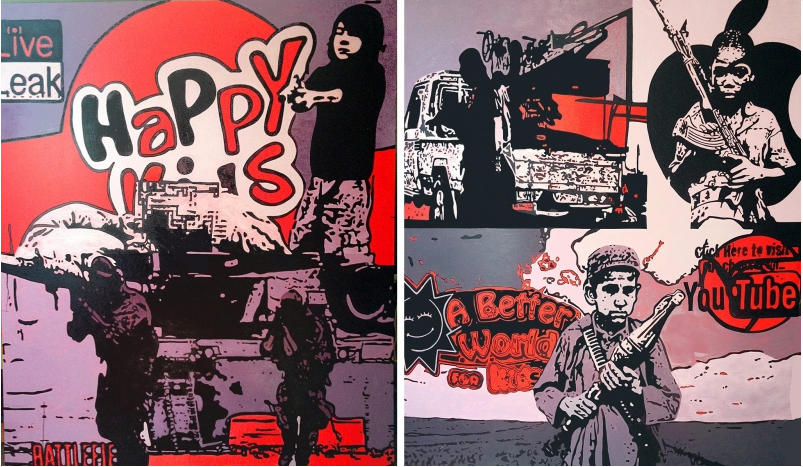

Serbia has an exhibition of three painters for example: Milena Dragicevic’s watery abstractions, in which plains of colour bleed into each other are arresting, as is Dragan Zdravkovic’s panoramic painting Enclave (2017), over four metres wide, which in spare forms, depicts a blocky unkempt municipal building of unclear purpose. But it is the two Pop Art-like painted diptychs by artist and academic (and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu fighter) Vladislav Scepanovic that dominate the space. Scepanovic paints composite images from YouTube and LiveLeak videos of conflict situations.

In Happy Kids (2017), the two canvases depict child soldiers rendered in oil in an almost stencil-like fashion. In the background is a wash of red and purple logos, perhaps pertaining to TV shows or children’s retailers. ‘A better world for kids’ reads one. The second diptych, The Chains of Evil (2016), opposes a panel in brown, grey and black paint of another child solider in front of a mountain of arms with a second canvas in which the logos for various vast multinational corporations are depicted (Pepsi, Samsung, etc). Scepanovic’s message isn’t subtle (but to be fair, in the biennale setting, it often pays not to be) but the vividness of his depiction is extraordinary.

These are ugly, brutal paintings, made to address an ugly, brutal subject. They feel out of place among much of the rest of the work in the Giardini, much of which is by turns intellectually engaging or merely entertaining, but all ultimately safe. The national pavilions at Venice offer a microcosm of the global world; Scepanvoic’s work serves as a reminder to the metropolitan western elite that dominates art’s circulation that art – and life – is not all fun and games.