Peng resurrects reels of 8.75mm film print to explore myth, memory and historical research

“He believes in words, not people.” A line spoken by the narrator in Afternoon Hearsay (2025), the artist Peng Zuqiang’s most recent three-channel film installation, describes an unnamed man who attempted to live according to the written word and didn’t believe he could ever be wrong. The phrase, though, pinpoints a persistent tension between words and feelings in the artist’s work.

Peng brings varied vocabularies to his moving-image practice: one that is rooted in words – in the rigorous research on film both as a medium and as a subject – and another that is attuned to his aesthetic instincts and affective forms of storytelling. There is an enchanting contradiction between the sharp intentions and critical thinking underpinning his projects, and the ambiguous textures of the actual works.

I first encountered Peng through his words, when he translated for a Chinese art magazine I edited during his student days. When we finally met at an exhibition he participated in, I was struck by an eloquence of a very different kind in his art – not the verbal precision I had perceived in his writing, but an emphatic refusal of clarity in the works’ sights and sounds, which spoke louder than any words could.

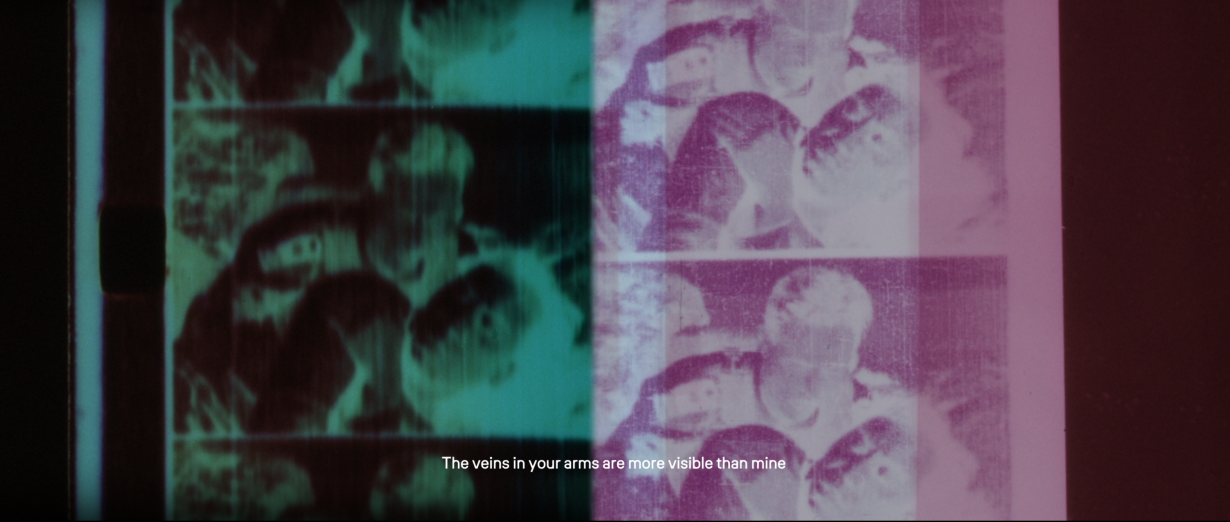

The work I saw was an early version of a five-channel video installation, keep in touch (2021). It unfolds through scenes of hand gestures and bodies coming into contact with each other: two men of colour waiting by an overheating car and blasting music in the woods, a man spinning a pen with his fingers, two pairs of hands trimming each other’s nails, a woman applying Tiger Balm to her body, and hands joined by strings in a game of cat’s cradle. In voiceovers accompanying two of the scenes, in what seems like a private conversation between friends, unnamed interlocutors recount past experiences of queer encounters. In essence, keep in touch is about the subtle and transient ways we connect with one another, particularly in the context of queer interrelations, where intents are often communicated in an ambiguous manner – through hints and gestures, whispers and hearsay.

Super 8, 16mm and 35mm transferred to digital, 5.1 surround sound, 18 min.

Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai

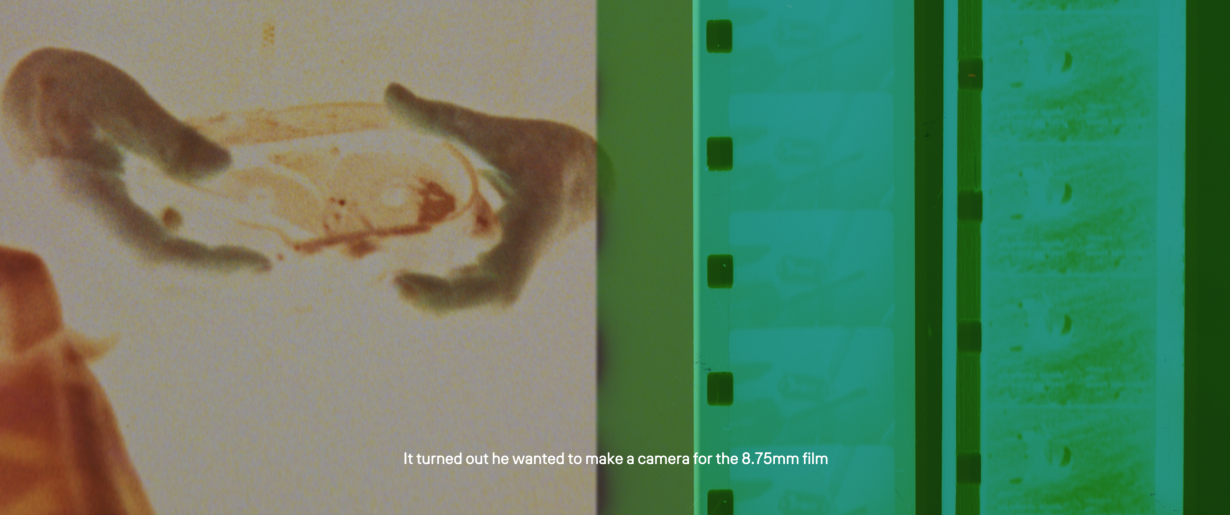

Hearsay and minor histories find their ways into Afternoon Hearsay, the artist’s most recent film interweaving historical research, speculation and fabulation. The work is inspired by an obscure chapter in China’s cinematic history relating to the use of 8.75mm film, a narrow-gauge, lightweight film that was manufactured in China between the 1960s and 80s, as a domestic alternative to Kodak’s Super 8. There was, however, one crucial difference between the American product and its Chinese alternative: there was no camera for the 8.75mm film. It could not record but only distribute; it was designed purely as a medium for the controlled dissemination of information by the State at a low cost. Entertainment, education, newsreels and propaganda were printed onto its reels and carried by mobile projection units to remote regions of the country. The 8.75mm film stock thus functioned as both a technological and ideological instrument – a means of connecting the rural masses while maintaining centralised authorship over what could be seen.

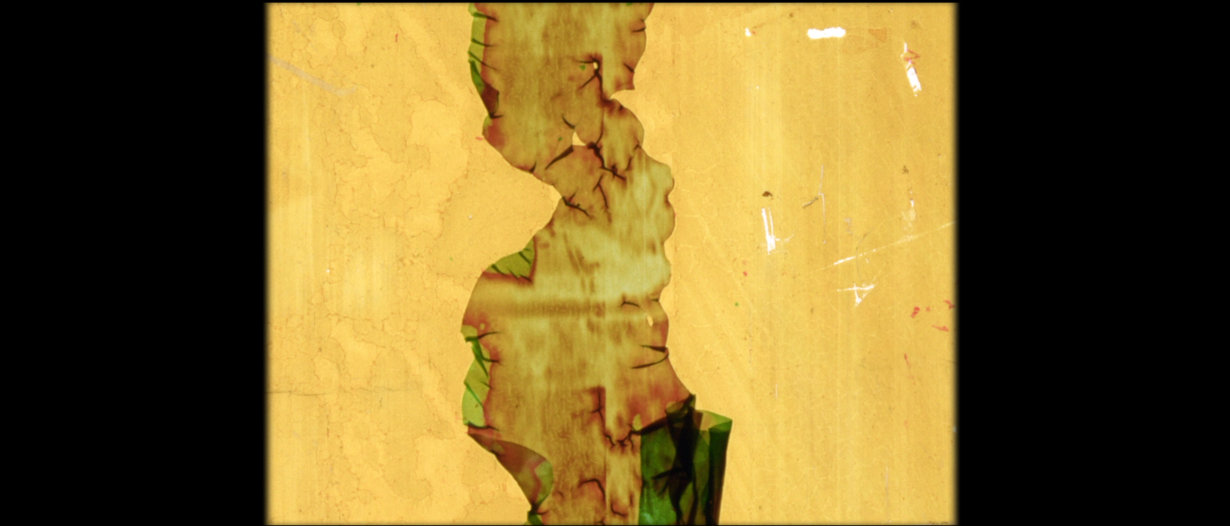

Peng resurrects this forgotten medium by collecting surviving reels of 8.75mm film print and reworking them through a cameraless process. These archival fragments are photogrammed onto 16mm and 35mm colour negatives, then pieced together in a montage with contemporary Super 8 footage the artist shot in rural China. The juxtaposition of these materials – obsolete and current, institutional and personal – creates a dialogue between eras, between the image as instrument and the image as witness.

At the heart of Afternoon Hearsay lies a fascination with the infrastructures of imagemaking: what happens behind the camera, inside the projector, within the sociopolitical mechanisms that give an image its legibility. Peng approaches these mechanisms by working directly with the materials of cinema – celluloid, light, sound – and letting them speak. Accordingly, the work begins not with narrative but with movement. Strips of film sway across the screen horizontally and vertically, gently oscillating.

The narrative structure in Afternoon Hearsay is held together by a constellation of partial memories. Speaking in Mandarin Chinese, four unnamed narrators recount strange happenings: fires breaking out after screenings, people vanishing, dreams merging with scenes from projected films. Only towards the end of the film is 8.75mm film directly referenced by a female narrator, as she describes someone who once tried to invent a camera for the special format film and showed her the footage he had shot, worrying that he would “forget

things in the future”. These narrations blur truth and myth, memories and hearsay, mirroring the instability of the images themselves.

Super 8, 16mm and 35mm transferred to digital, 5.1 surround sound, 18 min.

Courtesy the artist and Antenna Space, Shanghai

That same sensitivity to time, touch, memory and resistance is

encapsulated in Déjà vu (2023), an installation that weaves film, sound, text and sculpture into a single, trembling gesture. The work was created in the wake of the White Paper Movement – an outpouring of public protest that spread across China during late 2022, sparked by frustration with the country’s strict zero-Covid policy and intensified by the 24 November fire that killed ten people in a building under lockdown in Ürümqi, Xinjiang. For Peng, the movement was not only a moment of collective awakening but also a testimony to the complex ways dissent is amplified, recorded, remembered and suppressed, as evidenced by the rapid censorship and erasure of terms like ‘white paper’ and ‘pandemic’ from all Chinese media following the protests.

During this period of adversity, Peng began experimenting with cameraless imagemaking, as he felt he couldn’t capture anything on camera that would hold the weight of the events unravelling at the time. In Déjà vu, 30 metres of metal rescue wire – the kind used by emergency workers during highrise evacuations – is exposed directly onto 30 metres of 16mm black-and-white negatives. The wire leaves its own light-trace, a spectral imprint that registers contact and resilience. The resulting photogram is projected via a 16mm film projector, typically onto a window, positioning the wire literally on the threshold between inside and out, private reflection and public view.

The accompanying first-person narration in Déjà vu moves between confession and observation, interweaving memories of physical injury and harm from accidents, hate crimes and police brutality experienced firsthand or observed and overheard by the narrator. The booming bass rhythm that runs beneath the film is derived from protest chants recorded during the 2022 protests, stripped of words, leaving only a pulsating beat. Independent of the 16mm projection, the digital audio loops continuously; with each cycle, different fragments of the narration become illegible, as if eroded by time or noise. Mirroring this illusive breakage and violence enacted on bodies is a small clay sculpture sitting by the projector. It’s a replica of a Qing dynasty brush rest in the shape of a kneeling naked boy leaning forward on the floor. Much like the imprint of the rescue wire etched into the film’s celluloid, the visceral cracks and fissures marking the clay figure’s head and body attest to a history of violence, and an objectification of vulnerable bodies.

(installation view, Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, 2024).

Photo: Sander van Wettum. Courtesy the artist

Through these interferences – between sound and speech, rhythm and recollection, symbol and meaning – Déjà vu turns the act of listening into a pathway for empathy. The use of cameraless film allows Peng to work from touch rather than capture. Violence and endurance are traced not through spectacle but through residue – light, pressure, vibration. In an artist’s statement about the work, Peng writes, ‘if déjà vu is just a bodily sensation, not a real memory, is it possible to use one’s own physical memory to understand or relate to someone else’s experience?’ So the question remains, can one communicate through mere affects without attaching meaning to them? To what extent can one empathise with the feelings of others without a shared narrative? And how much can an artwork convey on its own without contexts or backstories? When ambiguity outweighs clarity, the efficacy of communication is at stake. However, in China, public voices of dissent can only survive in the spaces of art with deliberate ambiguities and rhetorical strategies obfuscating the real messages. The veiled nuances in artistic language become both protection and deflection, enabling the artists to speak as long as they don’t say explicitly what they mean.

In a complex and often volatile political landscape, words have long held the power not only to identify but also to erase, mislead, wound and persecute. This deep-seated historical and political undercurrent, while frequently concealed beneath the immediate surface of the works, forms a crucial lens through which to understand Peng’s artistic practice. His films meticulously probe the minute and delicate forms of communication that resist sanctioned interpretations and the pervasive threat of violence. Within them lies a deliberate embrace of pauses, hesitations and slippages – moments where minor feelings and private histories are afforded room to breathe and assert their existence.

Short-term Histories, is showing at the Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, through 26 April

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next Roots of Resilience: Tesfaye Urgessa