Dissenting political movements in the UK are marginalised; the digital image is everywhere. Kennard’s ouvre of DIY imagemaking is starting to resemble a halcyon era of political expression

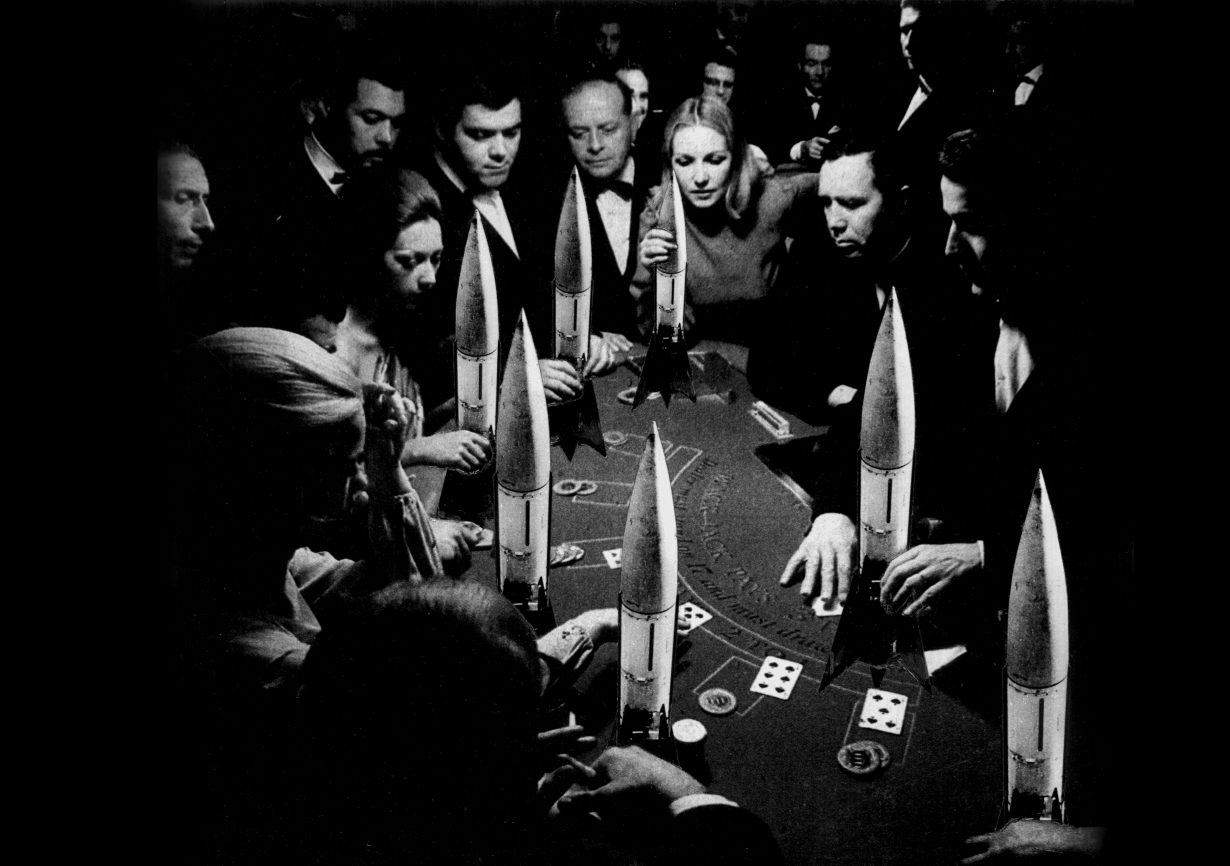

Peter Kennard’s retrospective at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, Archive of Dissent, opens with a workspace the artist has set up in the gallery’s former library. Bundled stacks of newspapers line the corners of the floor, and older, yellowed ones with ashen scars and slashes through the pages hang in frames on the wall; a selection of Kennard’s agitprop posters are pasted onto boards that visitors can flick through like they’re in a shop; a table offers photobooks and political texts for visitors to read. In the adjoining space, The People’s University of the East End (2024) borrows its title from that library’s colloquial name. Comprising a set of placards on wood poles, fixed into vices on the floor and crowded into one corner of the room, the series charts changing social – and socialist – concerns from the mid-1960s to the present. Among the placards, there are visual allusions (none of the signs here have the slogans one might expect from a political banner) to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND); campaigns against Anglo-American military aggression; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; and Israel’s genocide in Gaza. This is the tenor of Kennard’s work: a longstanding concern with confronting political and media power, and how DIY approaches to image-making have endured as a means to criticise such power. As if to bottle this definition in one work, a nearby vitrine titled Worktop (1966–2024) provides a ‘time capsule of the artist’s process’ (as per the wall text): a hotch-potch of books, newspapers and photographs covering the same subjects as The People’s University, as well as scissors and glue, a craft knife and a tape measure, paints and pens.

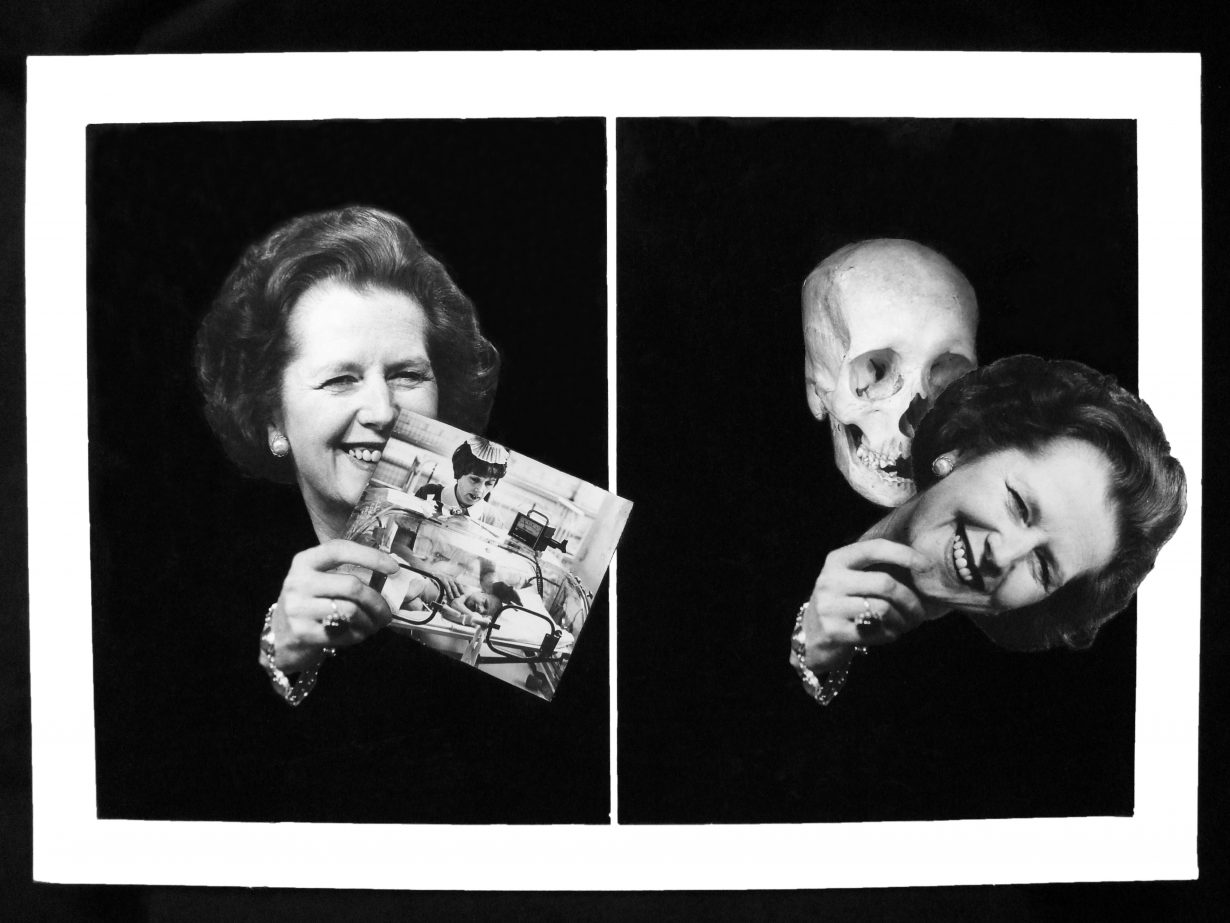

At their best, Kennard’s visual expression of movements that opposed racism, poverty and war condensed their ideas and demands into sharp images. His 1982 collage in support of Solidarność (Solidarity) – Poland’s independent and antiauthoritarian trade union – is a hasty and cheap construction, with the union’s logo clearly sellotaped to a sheet of A4 paper. On that sheet is a bayonet in photomontage, cutting through the trade union’s logo (‘Solidarność’ in red), suggesting both the will of the government to destroy the movement, and the power of the movement to destroy the government. You can draw a line from this to last year’s painting of the Palestine flag, with blood from the red of the triangle bleeding into the white between its green and black stripes. The flag is less imaginative than one of his many antinuclear montages, Union Mask (2007), which depicts Earth wearing a gas mask with the UK and US flags inserted into its eyeholes and warheads jutting out of its mouth, but it is equally striking, and just as emblematic of the conflict it addresses.

The focus here is on Kennard’s solo work. As such, his collaborations with artist and cultural activist Cat Phillipps are not included, depriving us of one of his most widely reproduced images, Photo Op (2005), of Tony Blair grinning as he takes a selfie against a background of burning oil. Kennard and Phillipps worked digitally, making this image with Photoshop, and it has been recognised not just by its inclusion in the National Portrait Gallery, but also by its subsequent passing into meme lore. Two decades later, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the prevalence of images in contemporary culture, not least because anyone with an idea and access to an AI image generator could produce something similarand circulate it around the world in seconds.

Showing the type, and amount, of work that goes into Kennard’s photomontages is a shrewd move – as is including posters about Rupert Murdoch’s pernicious influence on British media and politics, and that media’s role in British imperialism. It reminds us that communities in recent decades felt just as assailed by images from colour newspapers or television as we do by Instagram and TikTok today. (It’s worth noting that Guy Debord and Marshall McLuhan published their influential critiques of media and the spectacle it engenders just before Kennard began his career, as is the fact that Kennard’s first solo exhibition, Stop, was held in 1968, the same year that Murdoch bought his first British publication, the News of the World.) This sense of ubiquity should not induce politically minded artists to give up, but to think harder about which methods of making and sharing images are most likely to cut through to people who feel overwhelmed by visual material.

Archive of Dissent also hints at the impact of austerity over the last 15 years: what has replaced the old workers’ libraries – set up by trade unions and the twentieth-century socialist movement – and the adult education centres that were an early victim of the Thatcher government’s cuts is, as the existence of The People’s University implies, an informal combination of self-directed learning and an often atomised community activism.

But an idea of dissent, as a position and an act, in today’s UK is an altogether thornier proposition. For all the years of Kennard’s targeted artmaking, the imperial march of Murdoch’s News UK has, for the most part, dominated mainstream media, marginalising, ridiculing or demonising anyone who tries to turn dissenting knowledge into effective political action; society is being made it in its image, not ours. Though recently ousted, the late Conservative government spent 14 years criminalising protest, cutting arts funding to the bone and making universities (and especially arts and humanities degrees, where they haven’t been terminated) accessible only to the very wealthy or highly indebted, with the aim – not entirely successful, as the recent Gaza camps have shown – of smashing them as centres of dissidence and turning students into conforming consumers. Nothing in the Labour government’s manifesto or public statements offers realistic hope of this changing. (Kennard was, until his recent retirement, Emeritus Professor of Political Art at the Royal College of Art; I also work at the RCA, hit as hard as anywhere else by successive rises in tuition fees, and have heard nothing of a possible replacement, although someone from the college’s entrepreneurial unit spoke at a recent course induction of ‘incubating a cohort of potential start-up founders’, which is political in a different way.)

For most of his career, Kennard’s images were not confined to marginal spaces in such a way – plenty of them appeared in newspapers such as The Guardian or were made for Labour Party rallies and Greater London Council events (and are reproduced in a newspaper, given to visitors for free). Maybe the high visibility of these movements made the generation after Kennard’s cynical or complacent: more insidious than any government interventions to make protest less likely to succeed is a consensus that such ‘committed’ art is too earnest, too lacking in irony, or simply ineffectual. Such a view seemed the prevailing attitude between the fall of the Soviet bloc and the 2008 financial crisis, tying in with Francis Fukuyama’s famous declaration of The End of History and the Last Man (1992), and with nominally leftwing European political parties moving away from ideas of socialism. Kennard’s work, and photomontage in particular, anticipated the kind of antiadvertising sentiment widespread during that period, but for its thematic breadth and striking visual language has remained more relevant than, say, the anticonsumerist output of Adbusters.

Perhaps agitprop artmaking has to be especially good to avoid ridicule – the Telegraph review of this retrospective grudgingly admitted that the ‘overarching humanistic worldview’ of Kennard’s juxtapositions allowed his work to ‘transcend political divides’, even while disparaging the artist as ‘a bit conspiracist’ and as ‘the Baby Boomers’ Banksy’. While putting the work into a gallery may seem to neutralise its context, this does not prevent it from being reproduced at protests, on picket lines or in publications, and can hopefully prompt younger artists and designers who share Kennard’s political concerns to find contemporary ways of expressing them. Various long-term political currents reflected in Kennard’s work – opposition to Anglo-American foreign policy and nuclear war, as well as to the dominance of oligarch-owned media – coalesced in Corbyn’s Labour Party and have dispersed again since its defeat in 2019. Without such a large movement to hitch themselves to, anyone wanting to take the baton from Kennard will have to be prepared to work in the wilderness for some time.

The Archive of Dissent reminds us just how contemporary Kennard’s concerns about political and media power remain.

Archive of Dissent at Whitechapel Gallery, London, through 19 January 2025

Juliet Jacques is a writer, filmmaker and footballer based in London. Her latest book is The Woman in the Portrait, 2024