What makes contemporary art’s relation to ‘the contemporary’ more than symptomatic?

Crisis as Form continues philosopher Peter Osborne’s attempt to construct a critical concept of contemporary art. This project was begun in 2013 with Anywhere or Not at All and elaborated in The Postconceptual Condition (2018). Osborne’s idea is that ‘the contemporary’ articulates a new experience of time, as the coexistence of different times in a ‘disjunctive conjuncture’: this is the time of an increasingly globalised society, in which different social and historical times meet in the messy nonunity of the present.

Contemporary art is the art that corresponds to this situation. Osborne previously argued that contemporary art is conditioned by the legacy of conceptualism, the implication being that the barrier between art and nonart breaks down. Here the emphasis is on contemporary art’s ontology (what it most fundamentally is). Osborne argues for ‘the constitutive function of time in the artistic ontology of works’. Artworks are not just conditioned by the period in which they are made, they are retroactively transformed when activated in new contexts. Osborne illustrates this with a photo he took of a work by Juan Enrique Bedoya, itself a photo of Ed Ruscha’s 1962 painting of the word ‘oof’. Osborne explains that his photo contains nine ‘layers’ – references to various artworks and localities, to himself, to the symposium at which he presented his ideas, and so on. The claim is that Ruscha’s painting is transformed by subsequent engagements with it. This isn’t so different from the idea (once widely held) that artworks are ‘completed’ by the act of criticism, but Osborne makes the argument at the level of ontology, not meaning, implying that once upon a time this wasn’t the case. It is, in other words, specific to contemporary art. Whether this is plausible or not (Osborne takes the idea that ‘art is what it has become’ from Adorno, a thinker who predates ‘the contemporary’), the deeper claim is that works of contemporary art refract the experience of time that Osborne associates with ‘the contemporary’. All those ‘layers’ in Osborne’s photo of a photo of a painting are ‘temporalities’ that the artwork (here a snapshot) brings together in ‘disjunctive conjuncture’.

But what makes contemporary art’s relation to ‘the contemporary’ more than symptomatic? The answer appears to lie in the concepts embedded in the title: ‘crisis’ and ‘form’. If Osborne had previously defined ‘the contemporary’ as an effect of globalisation, he now conceives of it as a time in which crisis becomes permanent. ‘This destroys the subjective core of the concept of crisis’, since crisis no longer ‘registers a moment of decision within a process of transition’. In other words, we no longer experience crises as opportunities to change the world. This results in the contemporary political situation: ‘anti-capitalism without a post-capitalist imaginary – a series of received abstract ideas (freedom, equality, communism) severed from their historical meanings’. The suggestion is that contemporary art gives form to the ‘crisis of crisis’, thus raising it to critical consciousness. But the case studies develop this idea only tentatively. Generally, Osborne is more interested in the nature of art as such than its contemporaneity. The works he discusses – by Matias Faldbakken, Luis Camnitzer, Cady Noland and Marcel Duchamp – span nearly a century. The resonances between these works are found at the highest level of abstraction (their ‘ontology’), not the experience of contemporaneity. In short, the specificity and social significance of contemporary art are lost in Osborne’s analyses.

It is at times difficult to find a guiding thread in Crisis as Form. Concepts elaborated in previous works undergo subtle shifts of meaning; ‘the contemporary’ is periodised ever differently; artistic form, which Osborne had previously claimed was irrelevant to contemporary art, makes a comeback; the book’s central concept – ‘historical ontology’ – is ‘without a sustained theoretical development’, Osborne admits. This is not ‘tantalizing’, as he coyly suggests, but sloppy and irritating. Osborne’s wide-ranging project demands a systematic exposition. Crisis as Form fails to provide it.

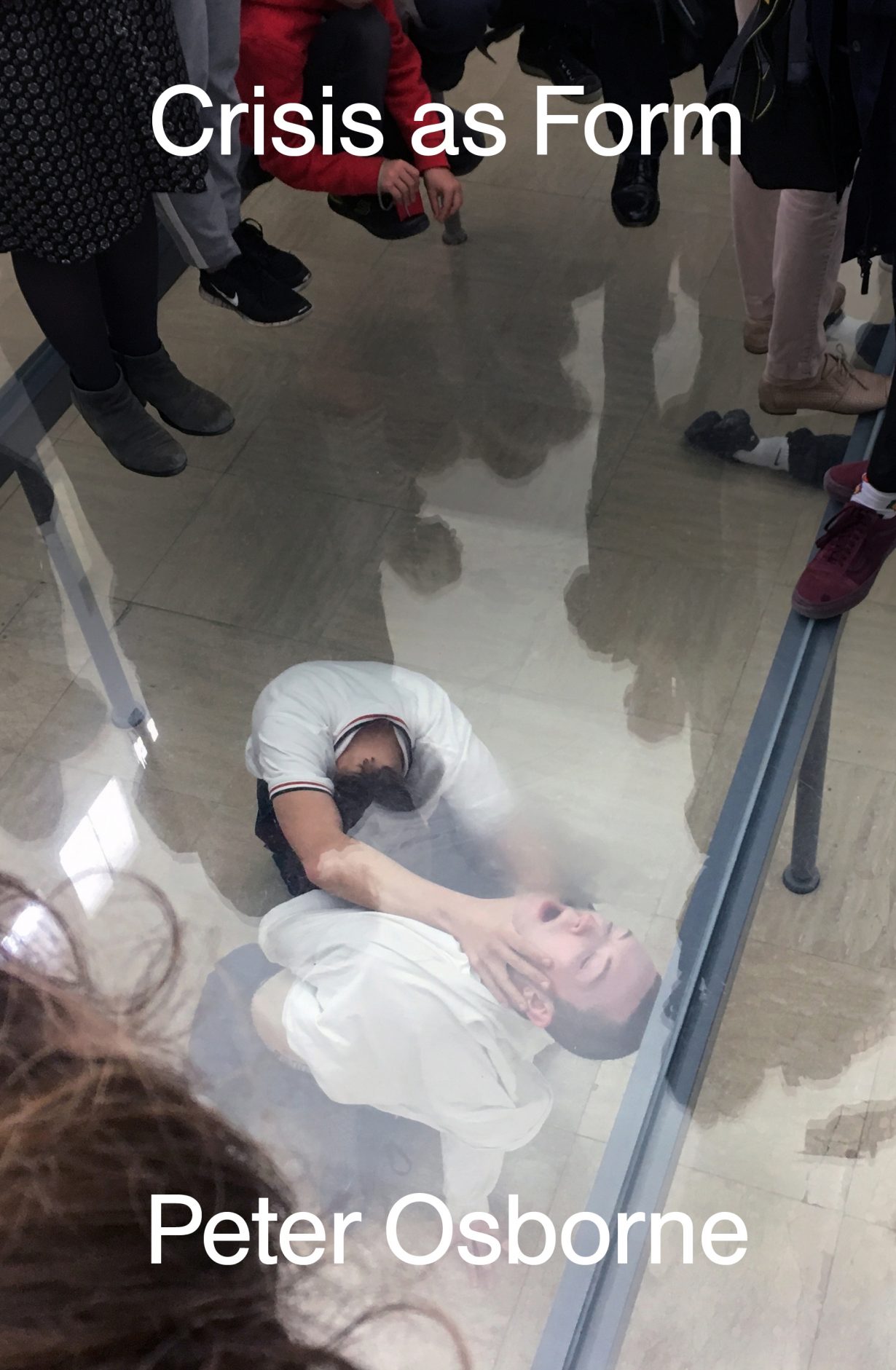

Crisis as Form by Peter Osborne

Verso, £19.99 (softcover)