An exhibition at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles makes in portraiture an argument for an expansive, humanistic feminism

This exhibition’s critical opening salvo – and its most direct – arrives in the form of its title, which refers to a comment by Willem de Kooning, supposedly hurled at his portraitist wife, Elaine. Portraits, he apparently declared, are ‘pictures girls make’. The stupidity of the comment highlights the masculine self-absorption of Abstract Expressionism, except, as curator Alison M. Gingeras concedes in the footnotes of the exhibition guide, de Kooning probably never did say that. Instead, it’s Elaine’s choice of words: ‘Bill always thought that portraits were pictures that girls made’. As reported by her biographer, Lee Hall, she continued: ‘So I made portraits. I had that area free; I had it to myself; I didn’t have to make decisions.’

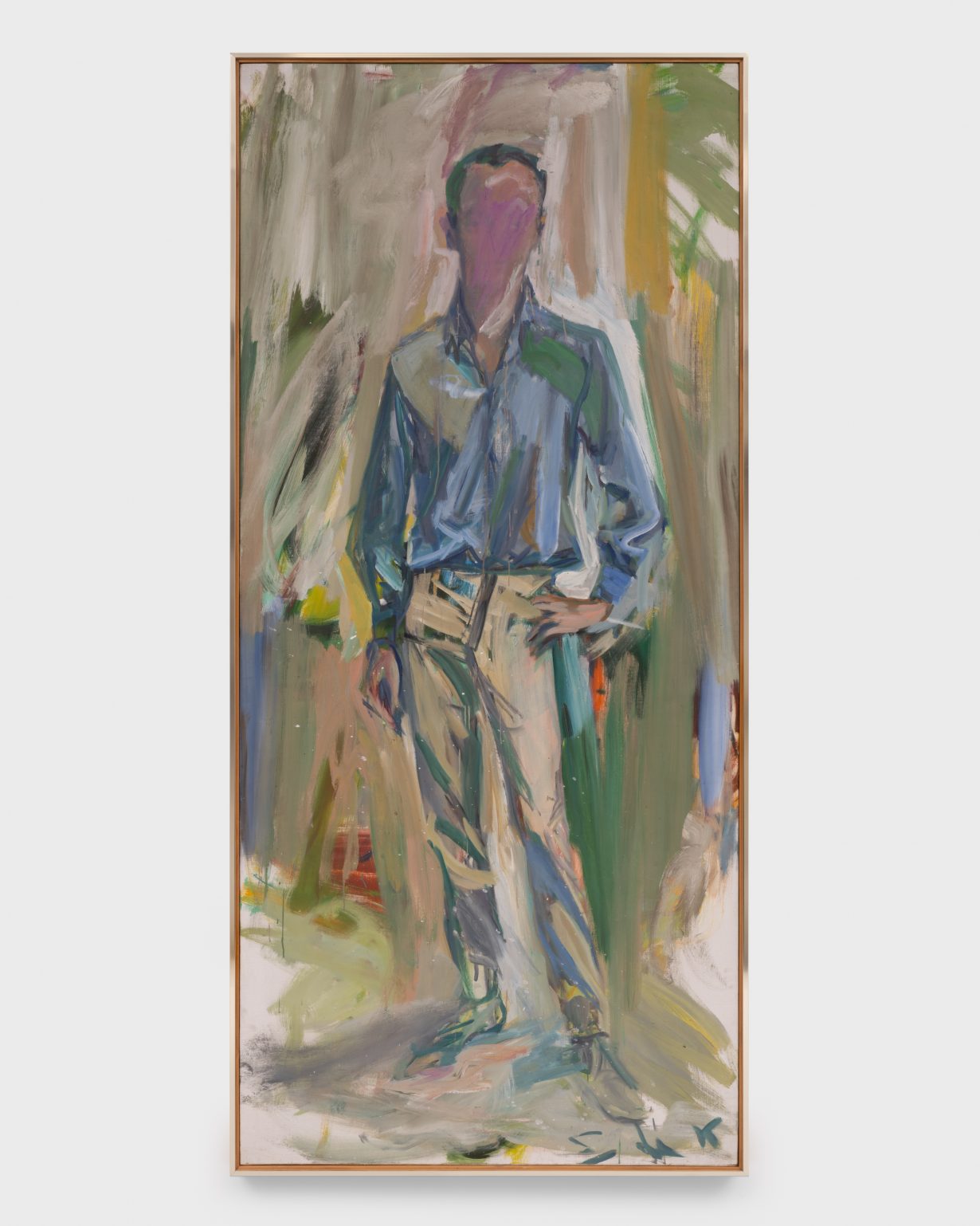

“Pictures Girls Make”: Portraitures is full of such sidesteps, but this deeply researched and profoundly enjoyable exhibition of work spanning from the present day back to the nineteenth century is somehow none the worse for its inconsistencies and fudgeries. Another complication: contrary to expectations set up by that title, around a third of the 60-odd artists in the show are men. Around as many pictures depict men too – including a striking, faceless portrait by Elaine de Kooning of Frank O’Hara (1962). Neither are all of the works in the show truly portraits (or ‘portraitures’, if you’ll indulge Gingeras’s winking Francophilia), if by that term you mean a picture that aims to represent a sitter’s personhood, as distinct from their bodily form.

Somewhere threading through the twists and turns of this exhibition is an argument for a vision of an expansive, humanistic feminism, one that encompasses a wide range of minority positions, from that of the first known Black American portraitist, Joshua Johnson (c. 1763– 1824), to the Franco-Japanese ‘dandy of the Jazz age’ Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita (1886–1968), to Argentine-born, Surrealist-adjacent Léonor Fini (1907–96), to Winfred Rembert (1945–2021), who taught himself leatherwork while incarcerated in various Georgia penitentiaries, and to the sex-positive artist-patron William N. Copley (1919–96), whose Love Canal (1980–81) shows a buxom woman adorned with tattoos including a phone number, the word ‘beer’ and the artist’s signature, ‘CPLY’.

Portraiture can take many forms, and perform many functions, as Gingeras would be the first to recognise. The six large spaces of Blum & Poe’s gallery have been painted in boldly contrasting shades – tomato, marigold, sage-green, hot pink – as a means of establishing thematic chapters in the show, which Gingeras has subtitled with lines excerpted from statements by artists in the exhibition. The grey-painted foyer – subtitled ‘This is what these lives looked like’ – contains the anonymous Portrait of a Creole Gentleman (c. nineteenth century) alongside Creole Duchess (2023) by the self-taught Alabaman painter Andrew LaMar Hopkins (whose quote that is), near Umar Rashid’s monumental painting from 2023 of a Black soldier in eighteenth-century uniform mounted on a rearing white steed and a dynamic painting of American footballers by Ernie Barnes from 1966.

It’s notable that the introductory notes of the exhibition resound not with issues related to gender, but race – an almost unavoidable theme in contemporary discourse around figuration. As Gingeras writes in her essay, ‘Whether spurred by political awakening or cynical opportunism, the race to foreground “new” artists of color has been driven mostly by a narrow focus on Black subject matter, while egregiously ignoring the complex histories of artists of color.’ One strategy that Gingeras adopts in widening this focus is to direct attention onto the long and nuanced history of diverse artists of colour, such as Creole and other mixed-heritage people, representing others who looked like themselves.

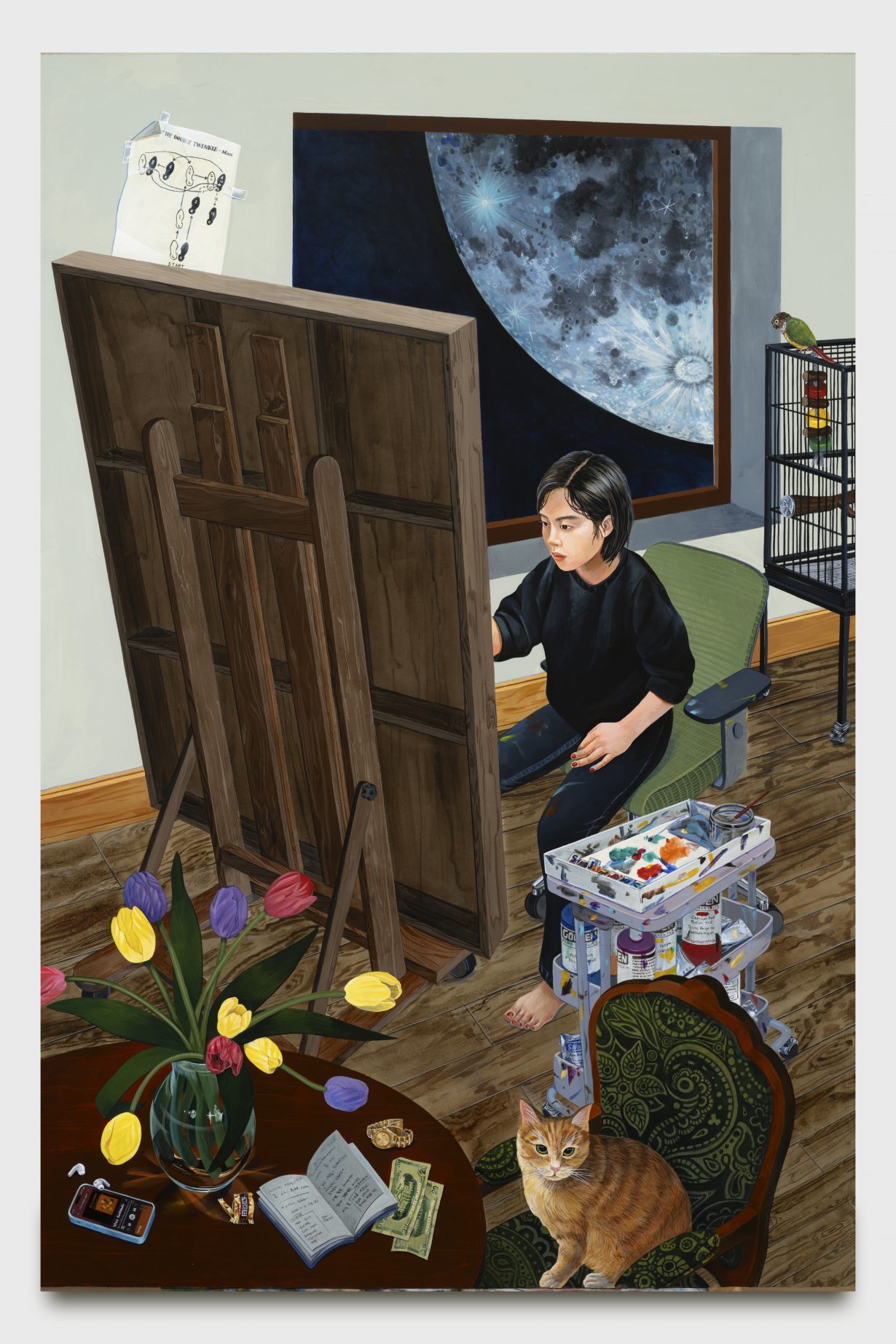

That theme segues into the biggest room of the show, which is also its most eclectic, focusing on self-portraiture and fittingly titled ‘I am not any one thing’, after the San Franciscan painter, teacher, mythologist, cat-lover and long-distance-swimmer Joan Brown, whose Woman and Sphinx #1 (1977) dominates the gallery. Almost every portraitist has also made self-portraits; depicting others goes hand in hand with depicting oneself. In this gallery, an intricate diptych self-portrait by Sally J. Han, Observing the Painter Working I and II (both 2023), converses with Hadi Falapishi’s witty Professional Painter 2 (2023), which depicts Falapishi in his underpants, painting his studio wall. Contrast such self-deprecation with Robert Colescott’s giant ripstop nylon flag, an acrylic-painted advertisement for his 1988 exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art, emblazoned with a seated self-portrait beside his boldfaced name and the dates of the show.

It’s a truism that a portrait-painter steals a glimpse into their subject’s interior life. What is less remarked on, and more prevalent, is portraiture’s function as the depiction of subjects’ self-determined exterior lives. It is a genre of poses, appearances, presentation and pretention. Many pictures in this show feature men and women standing stiffly and glaring down at the artist – and thus the viewer. Self-portraits by Juanita Guccione, Gertrude Abercrombie, Mela Muter and Zoya Cherkassky reveal almost nothing about their inner selves, but everything about their desire for dignity.

The most electrifying room in the exhibition is a green-painted gallery in which de Kooning’s debonair Frank O’Hara hangs adjacent to Larry Rivers’s brazen O’Hara Nude with Boots (1954). (Rivers was, at the time, O’Hara’s lover.) Also in the mix are June Leaf’s fondly irreverent painting of a nude Allen Ginsberg (c. 1995), Sam McKinniss’s similarly overwrought portrait of writer Joyce Carol Oates, Jill Mulleady’s foppish Hamlet II (2021) and, for good measure, Mark Grotjahn’s modest Untitled (Skull) (2023). (Naturally, Hamlet must have his Yorick.)

I’m aware that this room is dominated by white male artists, and white male subjects – even if queer. These are evidently not pictures that only girls make. This complexity is precisely what Gingeras refuses to shy away from; “Pictures Girls Make” is an exhibition that reveals – and revels in – the full breadth of this genre, and the inherent inclusiveness of its form. Portraiture is simultaneously major and minor in status, requiring centrality and marginality in order to stake its position as both culturally important and dissident.

“Pictures Girls Make”: Portraitures at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, 9 September – 21 October