Arts institutions formulate a rebuke to the conservative forces currently wreaking havoc in Brasilia – and scrutinise their own historic complicity

The leaders of Brazil’s state-funded arts institutions have found themselves in a bind ever since Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right presidency began at the start of 2019. Art was, or at least until the pandemic and Amazon fires took over the political agenda, an easy target for the president and his supporters, who found it tender prey in the politically expedient culture wars they are fond of whipping up, either picking up on its cost to the public purse or presenting work involving nudity as offensive to Christian morality. In one respect it has been an unfair battle, with the directors and curators of the institutions under attack, who might normally be among the first to defend the importance of art as a zone of free thinking and free speech, unable to mount any defence or make public comment for fear of losing their jobs. They have received criticism in the past for this perceived cowardice and yet, while their own voices may be silenced, both of São Paulo’s leading museums have now mounted robust defences, through their programming, of both culture in general, and the marginalised communities that have come under the cosh of Bolsonaro and his cronies.

The Museum of Art of São Paulo (MASP), under the directorship of Adriano Pedrosa, has introduced annual themes, from Histories of Sexuality in 2017 to Histories of Women and Feminism in 2019 (the Portuguese word ‘histórias’ is more open-ended than its direct English translation: closer to the English ‘stories’, the titles suggesting alternative, non-monolithic narratives of art history). In the two years running up to the next presidential election in 2022, the museum’s survey and solo exhibitions will continue to address the expansive retelling of the country’s art history under the banner Histories of Brazil, which will be followed by Indigenous Histories and Histories of Ecology. MASP might not say so in its official literature, but the longterm programme is a clear rebuke to the conservative forces currently wreaking havoc in Brasilia.

Until recently, Pinacoteca de São Paulo, in the city’s poorer downtown neighbourhood, had not offered anything near as radical. Yet, with a rehang of the collection (Pinacoteca concentrates on Brazilian art, whereas MASP has the largest holdings of European art in South America), director Jochen Volz has now also spoken. The small percentage of the museum’s collection previously on show was hung traditionally and chronologically. With this revamp, the German curator has brought a lot more work out of storage and introduced thematised galleries that tackle social and political issues as much as art-historical narratives.

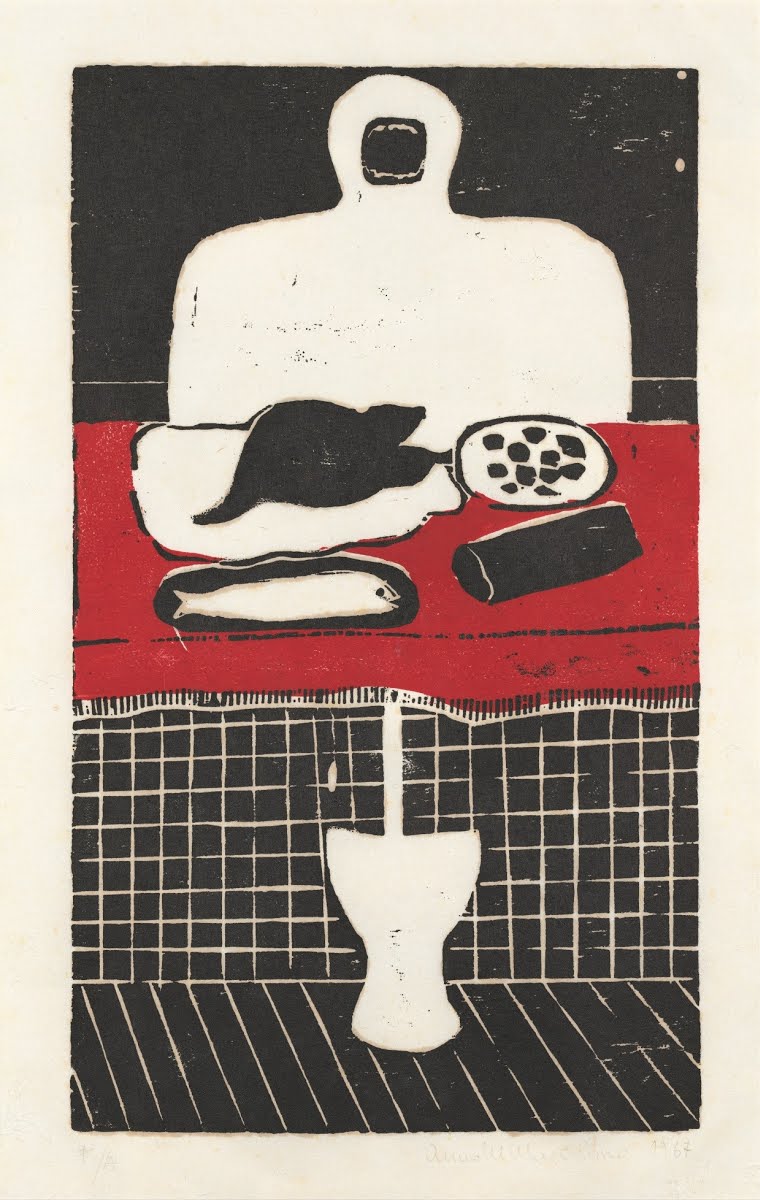

The opening room (of nineteen) sets the uncompromising tone with a plethora of works made as Brazil headed into the darkest days of the country’s dictatorship (1964–85), an era of which the current president has spoken fondly. The screaming faces, captured mid-protest, in Claudio Tozzi’s Pop acrylic painting Revolta (1968) find emotional resonance in the wide-mouthed, gurning agony of the semi-abstract figure, sat at a dinner table, that is the subject of Anna Maria Maiolino’s Glu…Glu…Glu... painted in 1967 and hung close by. Under the table, where one might expect the woman’s legs, Maiolino has depcited a toilet; the digestive process on show analogous to the shitty politics flowing through society both at the time the work was realised and today. A neofigurative painted assemblage by Tomoshige Kusuno, A Porta, (made in 1965, five years after the artist joined the second generation wave of emigration to Brazil from Japan) features the hellish scene of plaster hands clawing through a wooden door attached to a wood mount. It is complemented by another wall assemblage, Acontecimento (1965) by Nelson Leirner (who died last March), in which a taxidermied rat appears to be setting off across the first of a grid of traps, as yet unscathed. Two works from Antonio Manuel’s series Repressão outra vez-eis o saldo (1968), in which the viewer originally lifted a cover (no touching allowed now though), to reveal a screen-printed front-page of a newspaper reporting incidents of state violence, are more direct in their commentary. In the current climate the curatorial arrangement can’t help but come across as a Ghost of Marley warning of where things might end up if the country continues the path Bolsonaro seems set upon.

Further rooms are dedicated to landscape and nature, or works concerning female identity, or indigenous life (as well as a few taking on straightforwardly formal issues). Landscape is introduced in a wall text not as a genre, but as a term for work that might ‘approach a place without dominating it’: Antonio Parreiras’s sublime Ventania (The Gale, 1888), painted in the European style of the nineteenth century, portrays in oils a crouched figure beneath big brooding clouds, the curvature of the figure’s back matching trees bowed behind in the evident wind. In contrast is A Matança da Vaca no Sítio (1959) an arte popular painting by José Antônio da Silva, in which man is the destructive force: using levers and pulleys, a pair of farmers haul up a slaughtered cow by its hindlegs, its throat gushing blood, into a tree. Nature is presented as no more than a resource; the violent act perhaps a reminder of the damage intensive farming has enacted on the Brazilian landscape. In the background, through a rather thin row of trees, a row of houses stands in place of the cleared forest. Both Tarsila do Amaral’s Palmeiras (1925) and Eleonore Koch’s neighbouring painting Deserto do Arizona II (1995) also show signs of human habitation in a landscape, though this time without any actual figures being present. In the older work, a cluster of houses sit under the titular tree, in the later just a single abode is depicted among the sand dunes: both possess an eery emptiness, as if these places have been cleared and abandoned, by both humans and nature alike.

There’s no doubt that these arrangements are polemic in intent, and there are those who will bemoan that works are being used as mere plot devices to a political narrative predetermined by Volz and his curators rather than entirely by the artists themselves. Yet, to its credit, as much as the institution sits in judgment of the societal violence and discrimination that marks Brazil’s history, it doesn’t spare itself from the critical gaze. Indeed, it is where the Pinacoteca faces up to its own historic complicity that this rehang is at its most powerful.

On the same wall, in a gallery titled Violence and Resistance, a late-nineteenth-century painting of a dark-skinned woman by Antonio Ferrigno partners a 1981 photograph of a Yanomami woman by Claudia Andujar. In both figures there is a sense of fatigue. In the earlier work, Mulata Quitandeira (1893; the title suggests that she is a grocer), the woman sits on the dirt floor before the entrance to a hut, the produce she is selling on a blanket merging into the shadows behind. Andujar’s photograph is part of a series titled A vulnerabilidade do ser (The Vulnerability of Being) and comes out of her ongoing fight for justice for the indigenous populations of the Amazon. Both subjects confront the imposing frame of Dom Pedro II (1825–91), the last monarch of the Empire of Brazil, in a stately portrait in oils by Frenchman Raymond Monvoisin that hangs directly opposite. Next to him an eighteenth-century religious painting of the Virgin. Coloniser and church face off against those they oppressed. The juxtaposition is startling, not least on learning that Ferrigno, who moved to Brazil from Italy in 1893, specialised in depicting workers on coffee plantations, commissioned in the main by the plantation owners: people and property mixed.

Similarly pointed recontextualisations abound: one of Pinacoteca’s most iconic works, Candido Portinari’s Mestiço (1934), is a portrait of a handsome, shirtless man, the title suggesting one of the subject’s parents was Indigenous, the other European. In the background agricultural land spreads out. Portinari painted the work as a neorealist homage to the worker, but hanging in the same room are photographic projects by Jonathas de Andrade (Museum of the Northeast Man, 2013) and Paulo Nazareth (2010, from the series To Cover the Sun From Your Eyes) which highlight the fetishization of the dark-skinned body inherent in the historic painting. It’s a complex curatorial commentary, not without a dash of irony, that questions myriad intersectional privileges.

The neighbouring gallery is devoted to self-portraiture and it is here one of the most confrontational moments of the whole rehang occurs. In a salon arrangement of over two dozen paintings, mostly from the nineteenth century, the faces that stare out are all white and often rich-looking, bar, in the middle, Sidney Amaral’s 2016 self-portrait, Imolação (Immolation) in which the artist, who is black, holds a gun to his chin as if in the act of suicide.

Amaral’s work dealt with the racism inherent in Brazilian society (with depressing relevance elsewhere). He died in 2017, aged forty-four, of pancreatic cancer, just as he was gaining acceptance in the Brazilian artworld and the decision to place this painting, with its shocking subject, surrounded by white European faces is a formidable declaration of intent that acknowledges that art by black artists represents a minority of the museum’s holdings, even as it suggests that this kind of work will no longer be ignored. In a country in which violence against certain sectors of society – Afro-Brazilians, indigenous people, women – and against the natural world is all too common, sanctioned by the highest office of the land, this rehang marks an attempt to give voice to those people, at a time when they are at risk of being silenced in society at large. Yet it also highlights the fact that art and its institutions (themselves now under attack) have long been used, both consciously and unconsciously, as a weapon against the groups it is now foregrounding, denying them visibility, creating stereotypes, and confirming and reconfirming their lowly status in society at large. A problem acknowledged that remains a problem to resolve.