The Polo Experimental – which supports people with issues relating to mental health in their creative pursuits – is generating new forms of collectivism and, of course, a carnival

The sound of trumpet toots and the bass of a surdo drum echo through this small corner of the world’s largest urban forest, on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro, the city that grew around it. The music is coming from a carnival rehearsal session at the Polo Experimental, a squat concrete block that hosts people with various issues relating to mental health who visit daily to engage in all manner of creative pursuits. Polo is run by the Bispo do Rosário Contemporary Art Museum (MBRAC), five minutes’ walk away. The museum houses the archive of Arthur Bispo do Rosário, a Brazilian so-called outsider artist who died in 1989.

At the Polo Experimental the final touches are also being made to the costumes, puppets, lyrics and samba music that will come together in the museum’s own carnival bloco – a street party – that will process through the nearby streets during Carnival in February next year, in a riot of colour, crossdressing and cathartic hedonism. In another room, an embroidery workshop is underway. In a third, mosaics are being pieced together to be sold in the museum shop. There is also an atelier, known as Atelier Gaia, where ten artists – who are all supported by Rio’s municipal mental-health service – work independently on their own art projects. Sculptures and paintings fill every inch of the atelier walls and shelves, while the interior courtyards are scattered with discarded toys and other found objects awaiting transformation.

Diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, Bispo do Rosário spent 49 years, on and off, living in Rio’s psychiatric institutions. During that time he trawled local streets and asylum buildings, collecting pieces of scrap-metal and wood, cardboard, buttons, wheels, cassette tapes, combs, boots, flip flops… thousands of objects that he then organised and classified – a cataloguing of daily life that he believed was his divine mission – with the aim of constructing a new world without misery, illness or suffering.

In the three decades since his death, Bispo do Rosário’s collections, as well as his sculptures and intricate embroidery, have been exhibited in London and New York, at the Venice and São Paulo biennials, and at some of Brazil’s most prestigious art institutions. Born in 1909, in Sergipe, northeastern Brazil, Bispo do Rosário joined the navy as an adolescent in 1925. There, he trained as a boxer and went on to box professionally until an injury in 1936 left him lame. Two years later, working as a handyman in Rio de Janeiro and living with his employers, he had a divine revelation, presenting himself to monks at São Bento Monastery as being sent to judge the living and dead. From there, he was swiftly taken into psychiatric care.

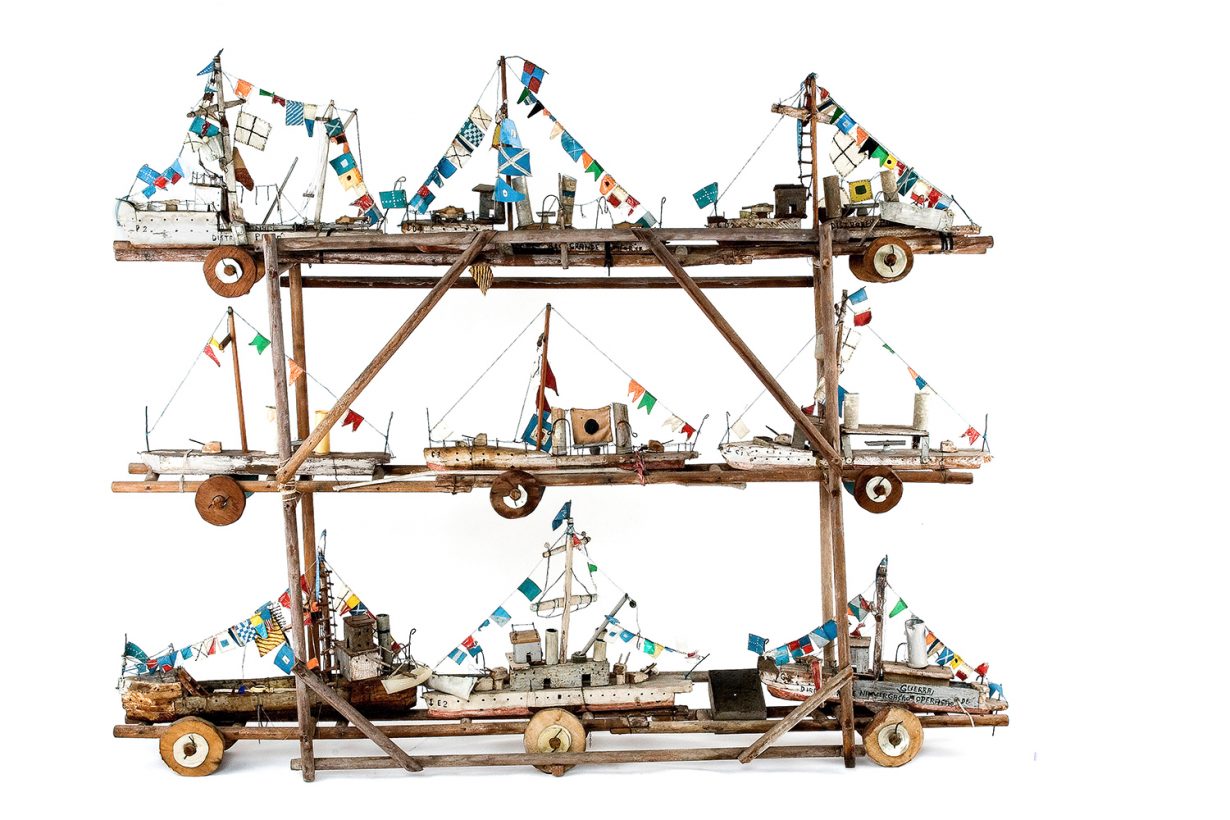

His most famous work, a ceremonial cloak, is rich in colour and adorned with curtain tie-backs. The act of wearing the cloak was part of the artwork, a physical embodiment of the symbols embroidered on it. Bispo do Rosário’s intention was to wear it on Judgment Day in order to be recognised by God, and to take with him the hundreds of women whose names he’d embroidered on the cloak. His Grande Veleiro (large sailboat) is another iconic artwork; a 158cm-long model boat with masts and embroidered sails – a throwback to his teenage years at sea.

MBRAC occupies one of the dozens of buildings at Colônia Juliano Moreira, the asylum in which Bispo do Rosário spent most of his time in psychiatric care. Originally a farm, the buildings were converted to become the Jacarepaguá Colônia de Psicopatas-Homens (Male Psychopaths Colony) in 1924 before being renamed after the pioneering psychiatrist Juliano Moreira. In 1924 it was a long way from Rio’s city centre, and deliberately so – a place to deposit society’s misfits. At its peak the colony housed 5,000 patients. There are now less than 200 in residence, and the government plans to scrap psychiatric inpatient care altogether in favour of community-based care, as part of Brazil’s mental-health reform programme.

The remaining abandoned buildings are slowly being reclaimed by the forest or occupied by low-income families as the city’s poor suburbs encroach ever closer. Despite the colony’s decline, and Bispo do Rosário’s posthumous rise to fame, MBRAC has resisted becoming a relic, instead a beacon of vitality and bringing life to the local community through art. Workshops, exhibitions, art residencies and performances all bring people from the local community and further afield to visit the museum and the nearby Polo Experimental. Arte Ponto Vital, an exhibition on show during my visit, traces a panorama of the art produced by patients at Colônia Juliano Moreira, from its dark asylum days to the present. The improvement in the residents’ lives is often clear in the work. Previously the patients were taught art, and their work reflected this ‘conditioning’, whereas at Atelier Gaia there is very little direction from the curators. Early paintings by Patricia Ruth are more abstract and muted than the colourful, expressive work she has been free to create since joining the atelier. “These are all things that I’ve seen in my head, so many beautiful things,” she tells me of the rows of brightly coloured houses that fill her most recent paintings. Arlindo Oliveira’s humorous mixed-media sculptures, figures with smiling faces and hands thrown up in childlike joy, contrast with the video of a darker performance piece in which

he reenacts a memory from a period when he was incarcerated alongside Bispo do Rosário in a nearby block for violent men.

Ruth and Oliveira were founding members of Atelier Gaia, back in the early 1990s, and both also experienced the ordeal of being institutionalised as teenagers, living at Colônia Juliano Moreira throughout the 70s and 80s. Although art has brought them purpose and healing, the atelier was not set up as a space for the kinds of art therapy first introduced to Brazil in the early twentieth century, in which doctors psychoanalysed their patients’ artworks as an insight into their emotions and unconscious. Instead, the professionals working alongside the artists at Atelier Gaia are curators, people from the world of art rather than of psychiatry. “It’s a place for free expression,” says museum and Atelier Gaia curator Ricardo Resende. “The artists’ work in the atelier is to think, to create. Psychiatrists and psychologists are always interested in visiting and observing what is developed and how the artistic process affects them, but there are no doctors accompanying their work.”

At Polo Experimental, Elihas di Jorge introduced me to some of the puppets he’d made. The impish twinkle in his eye made me wonder which end of the sanity spectrum he was on, a question I would never ask but that he could tell I was wondering. “That’s the fun thing about being here!” he said, as he grabbed a buxom brunette called Elvira, and twirled her lifesize body round the room. “The idea is that you don’t know who is who, there’s no distinction here between psychotics and neurotics. Everyone mixes together – it’s a universe of creativity, imagination and playfulness.”