Artists at risk back home are finding solace and relative safety in Thailand’s remote corners and art communities

Within the field of responsible exhibition-making and ethical art programming, risk management typically revolves around the elimination of health and safety hazards, background checks on sources of external funding, or perhaps, if the show at hand touches on sensitive topics, strategies to mitigate potential offence. In Thailand, however, another consideration is regularly factored in: the safety of any Myanmar citizens involved and of those close to, or affiliated with them.

Since the 1 February 2021 coup in Myanmar created a new generation of fugitive political activists – among them artists, filmmakers, musicians and creative workers – a calculated sense of curatorial care has underpinned numerous shows. In January 2022, the group exhibition Defiant Art: A Year of Resistance to the Myanmar Coup in Images featured several unattributed posters and memes, on the grounds that many artists ‘cannot be named for security reasons’. And, more recently, Trails of Absence & Symbols of Presence: Loss & Protest in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution comprised works by two artists using aliases: ‘Sai’ and ‘Ta Mwe’. Both exhibitions were hung along the curved wall on level four of the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC) – an unassuming yet high-footfall space – and staged by SEA Junction, a nonprofit that aims to make regional sociocultural and development issues accessible through talks as well as art. At the Trails of Absence panel talk, where speakers including James Rodehaver, the head of the UN human-rights team monitoring the situation in Myanmar, appeared in person, Sai joined via Zoom but kept his camera off – his pseudonym appeared in white font on a black screen as he spoke.

Other safeguards are subtler still, yet potentially no less impactful at mitigating conceivable harms. At Bangkok’s Jim Thompson Art Center in late September, a prominent Yangon-based curator gave a talk about the post-COVID-19 and post-coup realities of Yangon’s art market and Myanmar’s contemporary art scene: a period during which, the blurb teased, ‘the smallest string between the country and the international community was once again torn apart’. But instead of being broadcast live on Facebook, the talk was recorded, the centre’s director Gridthiya Gaweewong revealed in her closing remarks, so it could be edited – expunged of statements that might land him in trouble back in Myanmar – before being uploaded to YouTube. “I appreciate that,” said the curator.

Such concessions to the welfare of the Myanmar creative are happening worldwide – post-coup exhibitions and panel discussions of a similarly empathic and circumspect nature have been staged everywhere from Oslo to Sydney and London. But Thailand, which shares a porous 2,416km jungle border with Myanmar, itself has a history of popular uprisings and artivism in response to cycles of thwarted democracy and unchecked dictatorship. A refuge for Burmese migrants and refugees for decades (despite its not being a signatory to the 1951 UN refugee convention), Thailand is proving a hotbed of post-coup responses and solidarity.

Some Thai artists have responded to recent events in Myanmar in the way that feels most natural: the painter Ubatsat, for example, has recreated Guernica, Picasso’s cacophonous depiction of Hitler’s 1937 bombing of a village in northern Spain, but infused it with his own uncontained sense of horror and dread. Currently on prominent display at MAIIAM Museum of Contemporary Art in Chiang Mai, as part of the exhibition Living Another Future, Burmica (2022) overlays visual elements drawn from across Burmese political history – such as a sheet of corrugated iron in a bombed out village, and the ‘pro-democracy martyr’ Kyal Sin kneeling on the front lines of the 2021 protests – with mirrored inversions of Picasso’s abstracted cubist forms and figures. Meanwhile, a handful of Thai curators are collaborating with, or training, young Burmese artists with a view to helping them bypass the Thai art scene’s gatekeepers, gain exposure or better conceptualise their practices. Yet, above all, Thailand is offering space for Myanmar creatives of all stripes to self-organise, share experiences, forge connections and, to a degree, make art that speaks to the Myanmar military’s assault on their fledgling democracy and dreams – something that can’t, tragically, be said of the art scene in Yangon, where self-censorship is now pervasive.

An August 2021 post by Myanm/art, a leading Yangon gallery, offers a blunt reminder of the double whammy that hit Yangon’s contemporary art scene hard. While the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions in January 2021 meant that art spaces could reopen, and spurred a sense of cautious excitement about the future, ‘Relief was not to come,’ Myanm/art’s directors wrote. ‘On 1 February 2021, the military of Myanmar staged a coup, Aung San Suu Kyi was arrested, along with several elected officials, activists, filmmakers and musicians. The result was army personnel entering Yangon in force for the first time in nearly a decade. Courageous, stunning, and unifying protests turned deadly after several weeks and Yangon – along with the rest of the country – descended into chaos.’

The net effect of this military crackdown was a hollowing out of the creative sphere, as artists involved in the protests and Civil Disobedience Movement fled. ‘Some left the country, finding residency opportunities abroad,’ Myanm/art’s post continues. ‘Others left Yangon to shelter in their hometowns and villages, some of which are safer than the larger cities. Many more were imprisoned or disappeared.’ Meanwhile, scores of Myanmar’s cultural luminaries, including artists, writers, poets, cartoonists and film stars died in the third wave of the pandemic.

Nearly four years on from the coup, Yangon’s art scene remains active, even frothy in certain respects. “Everyone thinks that, with the military coup and COVID, the local art market is gone,” explained the Yangon-based curator during his talk. “No, the money is there, it’s just not in the contemporary market. It’s in all the traditional paintings, old master’s works, auctions.” But any buzz has dissipated. In a March 2020 opinion piece for ArtReview Asia, Myanm/art’s founder, Nathalie Johnston, hailed the many works being produced that probe the country’s complex historical layers, including ‘legacies of colonialism, military dictatorship, the quest for freedom and democracy, the problematic relations between the Burmese Buddhist majority and the numerous ethnic minorities in the country’. Yet works of this nature swiftly disappeared from Yangon galleries after the coup. And for good reason. “There are and has always been those who consciously create political art and those who wish to go beyond or work outside of the purely political,” she explains to me. “But they seem to be on opposite sides of the border now, with those inside Myanmar unable to make politicised art for fear of their safety and that of their families, and those outside who have the fearlessness to speak out.”

This climate of fear has been exacerbated by the introduction, in February this year, of a military conscription law that requires men aged eighteen to thirty-five years and women aged eighteen to twenty-seven to serve a minimum of two years in the military. “The conscription law has changed everything,” says Johnston. “Now it seems it’s not safe for young people to even gather.” Myanm/art is still hosting exhibitions, she adds, but “is not what it used to be: an active meeting place for young people, artists, researchers and visitors.”

In contrast, Thailand, whilst presenting its own latent risks (especially for undocumented immigrants, of which there are a growing number due to the conscription law), offers pro-resistance, antiauthoritarian Myanmar creatives more room for free expression – something that Limbo, a festival of ‘Thai-Myanmar creative and cultural events’ held in Chiang Mai in September, proved with aplomb. Activities during its three-week duration included a poetry and acoustic music evening, and a buffet where fire-grilled Burmese and Thai food was served, all of which seemed purpose-built to bring disparate groups of people together. But each event was framed by trauma-informed discussions, themes, narratives – or, in the case of those held at Some Space Gallery, art.

Documentary photographer Khin Sandar Nyut, for example, used mortar-round shells, recovered by her friends fighting in an armed insurgent group, the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force, to create sculptures and a printed runway carpet (Mortars: Junta’s residuals, 2024). Even the most joyous of Limbo’s activities – a display of Thangyat, a Burmese performance art that blends traditional drums with satirical verses often directed at the authorities – cut deep, contrasting comical asides with digs at corrupt Thai transport police and snarky commentary about Chiang Mai’s changing demographics. “Burmans coming waves by waves,” they chanted over a driving beat. “Here comes next batch, next batch / To the place of better survival / Let’s keep strong / We must go back home one day.”

Limbo was forged in exactly this pragmatic spirit: in the hope of fostering better connections between the exiled Myanmar artist- activist and the Thai equivalent, nurturing new connections and keeping strong. “We don’t know how long we’re going to be here,” says cocurator Ma Hnin, who runs the Chiang Mai-based collective A New Burma – an ‘ad-hoc community of loosely-connected creatives’ – and also organises a festival of music, food, art and film from Myanmar, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, each February. “As I see things, we’re not just guests. We need to also be growing with the community.” For her, this responsibility entails balancing out the parties and high jinks with serious issues-based exhibitions, such as When We See the Planes, a group show first staged in Bangkok in June, which brought to light the junta’s indiscriminate airstrikes on civilian targets (this highly controversial subject matter wasn’t flagged in the title, to minimise the chance of attracting unwelcome attention). Often documented online, such projects constitute “an archive of our revolution,” she says, as well as advocacy tools.

An Australian citizen, Hnin emigrated to Melbourne aged fourteen (following Myanmar’s brutally suppressed ‘8888 Uprising’ in 1988, her parents fled to a refugee camp on the Thai-Burma border and eventually gained asylum in Australia). But she moved to Yangon to run a bar and art space in the mid-2010s, at a time when the country was experiencing waves of investment amid democratic reform. Then, after fleeing in the wake of events of 2021, travelling aimlessly and spending time in Bangkok, she eventually settled in Chiang Mai – a city that has historically been a refuge for political exiles and economic migrants from Myanmar, especially nearby Shan State. “The beauty of Chiang Mai is it’s not like Bangkok,” she says. “Here we see each other everywhere – when there is an event the whole of Chiang Mai goes. And now, Thai artists are interacting more with Burmese artists.”

Cultivating these interactions for the purposes of Limbo wasn’t easy, for sociopolitical as well as logistical reasons. “What’s happening in Myanmar and what’s happening in Thailand are very different, even though we share and live under the same feelings of frustration,” says Hnin. To create co-understanding, she and two Thai curators, Somrak Sila (Limbo’s project director) and Thawiphat Praengoen, held workshops that sought to break down barriers and build trust. According to young Thai filmmaker and actor Jakkrapan Sriwichai (who collaborated with a Myanmar artist-activist who goes by the moniker Ants are Always Busy), these exercises – especially the playing of an activist-strategy card game called ‘Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution’ – spurred the participants to think hard “about how to make art that is not just an aesthetic thing, but has a hidden function”.

Not everyone is complimentary about such developments. One anonymous observer believes the 2021 coup gave an opening to anyone from Myanmar who wanted to bill themselves as a protest artist, resulting in “some fairly mediocre artists” being “taken seriously for the first time”. Comparing the pre-coup literature on Myanmar contemporary art with the tenor of post-coup international shows, it is also patently clear that efforts to push back against foreign curators’ pigeonholing of Myanmar artists as inherently political have fallen by the wayside. (Arguably, Burmese artists still remain, to quote a 2018 piece by art historian Yin Ker in Afterall, ‘an exhibit of “Myanmar” and a detainee of orientalism 2.0 couched in politicised rhetoric.’)

But even for those who voiced such complaints in the past, using art to speak out against the coup and hosting events like Limbo are important. “At this point, it is about finding a place where artists can express, as a group ideally, the conditions and historical context of Myanmar on their own terms,” says Johnston, who is now based in Sri Lanka. “Thailand is providing a safe haven for that practice. The crowd in Chiang Mai especially is creating their own platforms and keeping the artistic spirit of Myanmar alive.” She also points to the tense Thai border city of Mae Sot, where filmmakers, poets, artists and musicians number among the many thousands of Myanmar refugees, and where Artist’s Shelter, a filmmaker-run nonprofit that seeks to empower them to continue working safely, is active.

Look closely, and you’ll also see an evolution: the protest motifs and slogans widely exhibited in the wake of the 2021 coup have made way for more nuanced, biographical and honest works that tap into the personal perspectives, diasporic journeys and emotional responses of the displaced. This is art rooted in the realisation that the junta were not toppled by street protests, three-finger salutes or civil disobedience, and that there are new battles now being waged both inside and outside the country (including literal ones: much of Myanmar is today at war, a broad alliance of ethnic armed groups and a ‘People’s Defence Force’ seeking to overthrow the military regime). And in the realisation that psychological pain can, in fact, be generative.

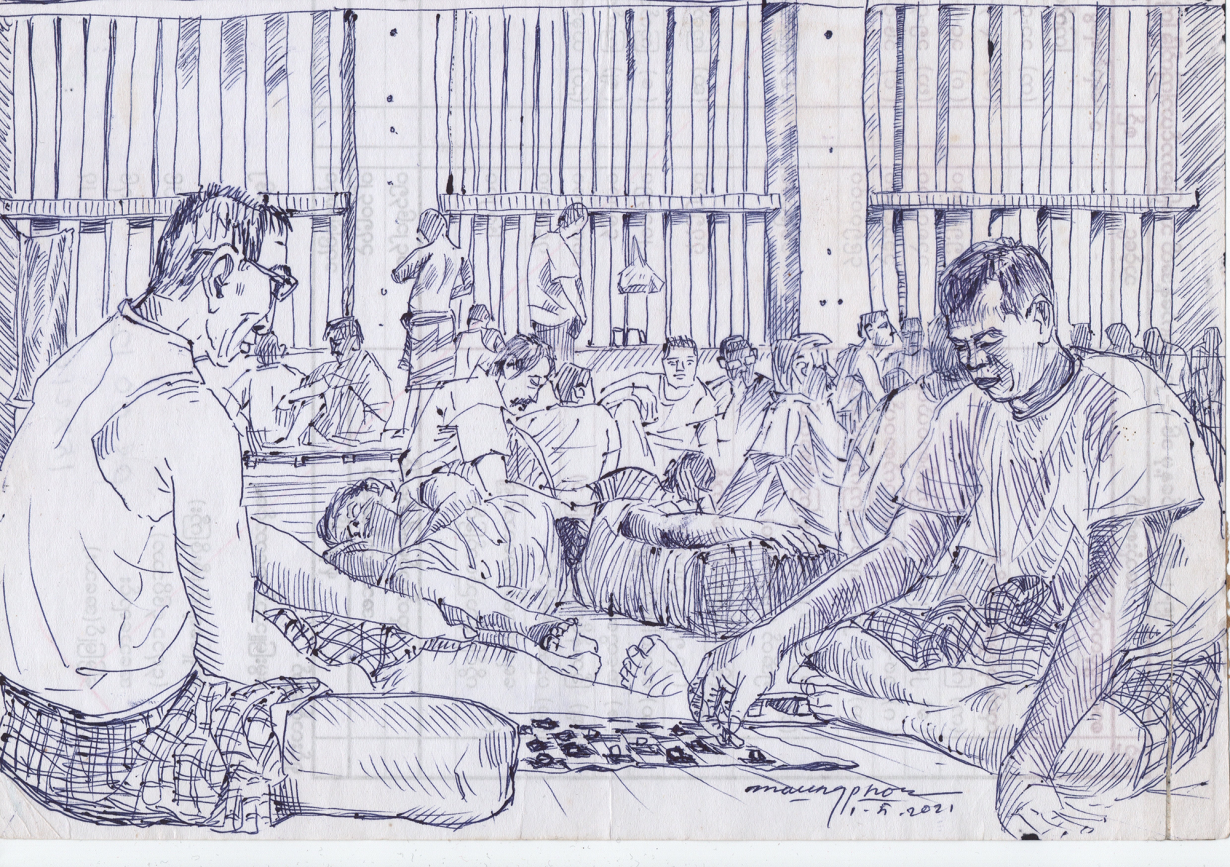

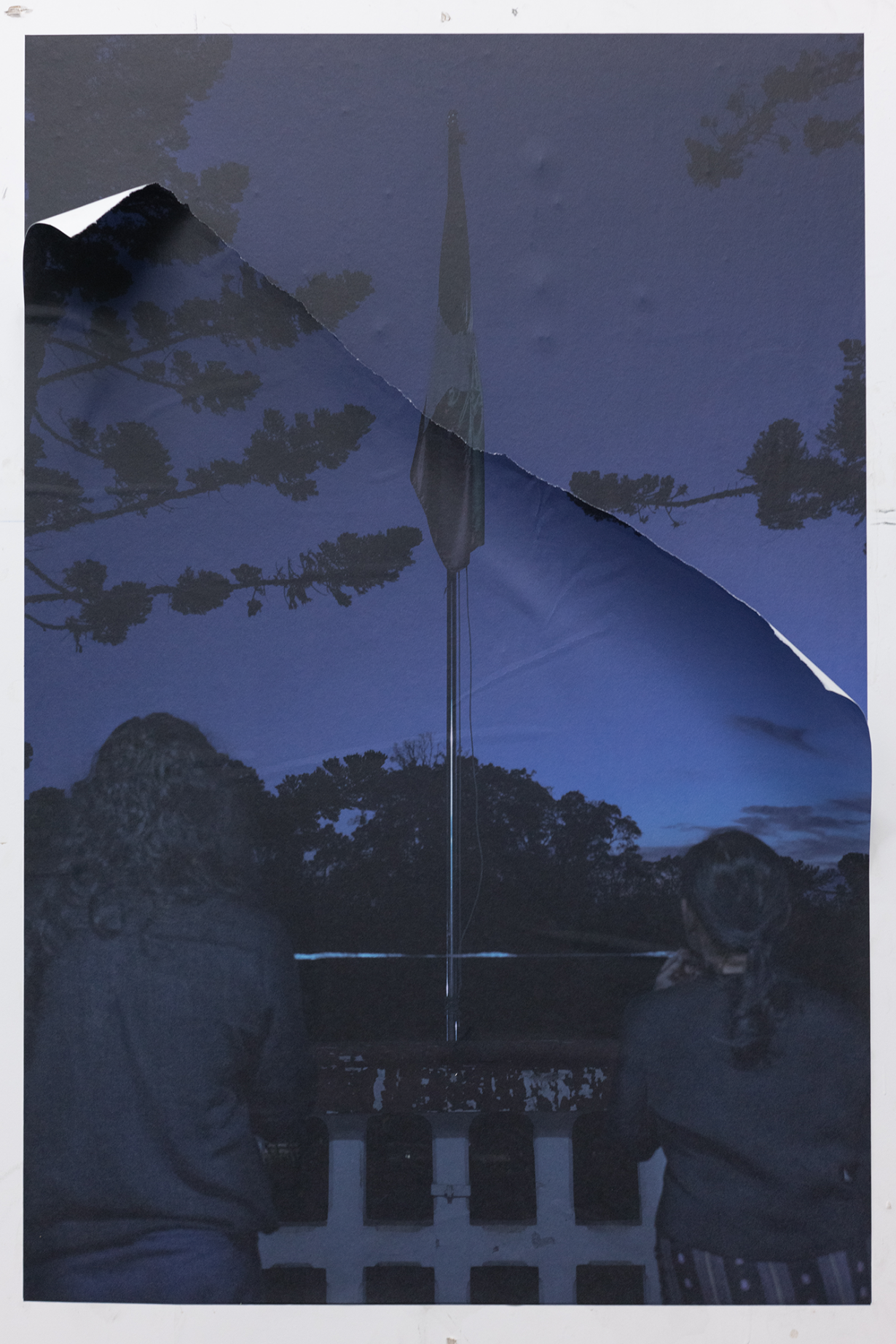

At one extreme, this realisation has resulted in works as blunt and blistering as Annt Hmue Mahr’s Goodbye Rebel! (2024), a photoseries documenting the Mae Sot funeral of FL3XX, a rapper who died from kidney failure last January. Shown at Limbo, these stark black-and- white images of his friends huddling around his coffin and raising three fingers in tribute were accompanied by captions explaining how the young rapper had, prior to his fleeing to Mae Sot, jumped from a five-storey building to escape Myanmar’s military police (he survived, but some of his friends didn’t). And at the other extreme, it has resulted in series as subdued and evocative as Sai’s Trails of Absence (2021–, exhibited at the BACC twice this year), which comprises mixed-media photographs of he and his mother taken while he was in hiding. In them, they hold pieces of tape between them to denote the resilience of their strained bond. Fabrics smuggled out from Myanmar’s prisons, woven together in the style of Shan carpets, mask their identities.

Sai’s trajectory as a contemporary artist, with its origins in persecution, global ties and strong links to Thailand, is illustrative – doubly so given that he never set out to be one. Prior to the coup, he had been working as a curator alongside his wife, and preparing to stage Kalaw Contemporary Arts Festival, a biennale in the hillside town of Kalaw, Shan State, focusing on marginalised artists. “The international community don’t know much about the narratives, cultures or experiences of Myanmar’s ethnic minorities. We intended to fill that gap,” he says. These plans were shelved, however, when the coup happened. Soon Sai was contributing to the protest movement in Yangon by making riot shields and creating infographics about how best to deal with teargas and gunshot wounds. And then came a daring move: he headed back to Taunggyi, the capital of Shan state, where his father – the state’s chief minister – was in prison on trumped-up charges, and his mother under house arrest. The images that comprise Trails of Absence were shot in the spacious rooms of the colonial-era house where his mother was being held – and, to this day, remains.

Since he fled the country (after 244 days in hiding), Sai has been using his autobiographical art as a tool to raise international awareness about political prisoners at large, and the horrors of an often-overlooked conflict. Thus far, this advocacy work – which dovetails with a wider interest in peacebuilding and transitional justice (processes likely to be invaluable if and when a future democratic Myanmar becomes a reality) – has brought him into contact with numerous sympathetic politicians, such as Tulip Saddiq, the Labour MP for Hampstead and Highgate in the UK, and members of the US Congress, where he recently appeared at a congressional briefing about arbitrary detention in Myanmar. But many of his most fruitful connec- tions were forged in Thailand. Forthcoming is a new chapter of Trails of Absence, based on his recent dialogues with survivors of abduction and torture in the border regions. And whilst Sai has encountered prejudice in Thailand (such as a landlord who refused to rent to him simply because he is from Myanmar), and has firm red lines governing what he will and won’t do here (“I choose not to take part in exhibitions where lots of Myanmar people gather, as there’s a risk that Myanmar intelligence could monitor them,” he says), he has felt welcomed by the country’s art community and civil society. “When Thai artists and activists reached out to me, in the form of programming and solidarity, I was touched,” he says. “That was the first step to my feeling closer to this country. Now Thailand is, in a way, the next best thing to home.”

Can’t Stop Won’t Stop Festival will take place 20–22 February 2025

From the Winter 2024 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.